Early Life

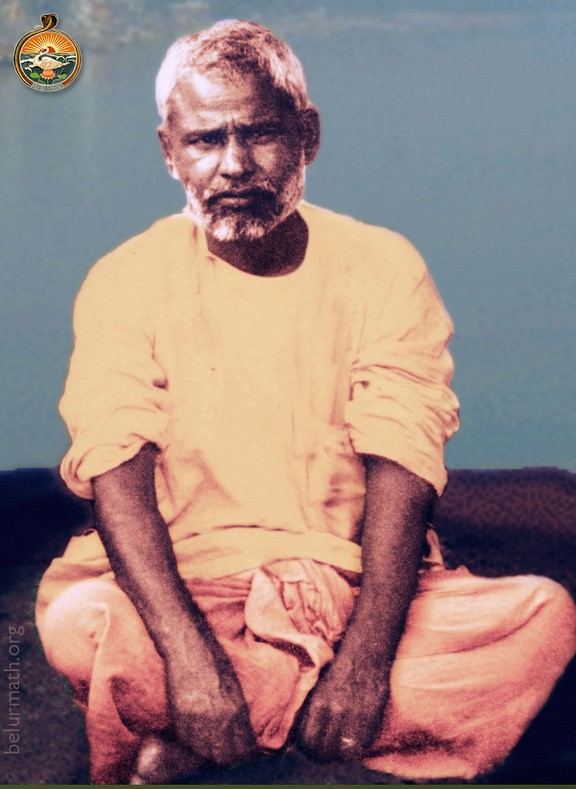

‘Latu is the greatest miracle of Sri Ramakrishna’, Swamiji once said with reference to Swami Adbhutananda. ‘Having absolutely no education, he has attained to the highest wisdom simply at the touch of the Master.’ Yes, Latu Maharaj, by which name Swami Adbhutananda was popularly known, was the peer of the Master in this respect that he was entirely innocent of the knowledge of the three R’s. Nay, he even surpassed the Master in this ignorance; for whereas the Master could somehow manage to read and write, with Latu Maharaj any reading or writing was out of the question. Once Sri Ramakrishna attempted to teach young Latu how to read and write. But in spite of repeated attempts Latu pronounced the Bengali alphabet in such a distorted way that the Master, out of sheer despair, gave up the attempt to educate Latu. It did not matter, however, that Latu had no book-learning. Books supply us knowledge by proxy, as it were. Latu had direct access to the fountainhead of Knowledge. The result was that great scholars and philosophers would sit dumb at his feet to hear the words of wisdom that dropped from his lips. Sri Ramakrishna used to say that when a ray of light comes from the Great Source of all light, all book-learning loses its value. His own life bore testimony to this fact. And to some extent this could be witnessed even in the life of Swami Adbhutananda, his disciple.

The early name of Swami Adbhutananda was Rakhturam, which was shortened to Latu. He was born of humble parents in a village in the district of Chapra in Bihar. His early life is shrouded in obscurity. It was very difficult to draw him out on that point. As a sannyasin, he was discreetly silent on matters relating to his home and relations. If anybody would ask him any question about his early days he would sharply answer, ‘Giving up all thought about God will you be busy about these trifles?’ And then he would become so grave that the questioner would be awed into silence. Once a devotee expressed a desire to write a biography of Latu Maharaj. To this he raised objection saying, ‘What is the use of writing my life? If you want to write a biography, just write the biography of the Master and of Swamiji. That will be doing good to the world.’

From the meagre details that fell from the lips of Latu Maharaj in his unguarded moments it was known that his parents were very poor—so much so that they could hardly make both ends meet in spite of their constant hard labour. Scarcely was Latu five years old when he lost both his parents. His uncle then looked after him. As ill luck would have it, Latu’s uncle also had an unfortunate turn of circumstances and he had to leave his parental homestead and come to Calcutta for means of livelihood. The boy Latu also accompanied him, and after a hard struggle for some days in Calcutta got employment as a house-boy in the house of Ramchandra Datta, who was a devotee of Sri Ramakrishna.

As a servant, Latu was hard-working and faithful, but he had a keen sense of self-respect even at that early age. Once a friend of Ramchandra gave the indication of a suspicion that Latu might pocket some money from the amount given him for marketing. Young Latu at once flared up and said in half Bengali and half Hindi words (which constituted his means of communication), ‘Know for certain, sir, I am a servant but not a thief.’ With such firmness and dignity did he utter these words that the man was at once silenced. But he reported the matter to Ramchandra, who, however, supported Latu rather than his friend—the boy-servant had already won the confidence of the master so much. Unsophisticated as he was, Latu was very plain-spoken, sometimes to the point of supposed rudeness. And he was no respecter of persons. As such, even the friends of Ramchandra had sometimes to fear Latu. This characteristic, good or bad, could be seen in Latu Maharaj throughout his life.

Ramchandra being a devotee, his house had a religious atmosphere and religious discussions could be heard there. This greatly influenced the mind of Latu, especially at his impressionable age. Once Latu heard Ram Babu saying, ‘One who is sincere and earnest about God realises Him as sure as anything’, ‘One should go into solitude and pray and weep for Him, then and then only will He reveal Himself’, and such other things. These simple words impressed Latu so much that throughout his whole life he remembered them, and often would he repeat them to others exactly as they were heard. From these words he found a clue as to how to build up his religious life, and they shaped his life. Sometimes Latu could be seen lying down, covering himself with a blanket, his eyes moistened with tears which he was wiping with his left hand. The kind ladies of the house thought that the young boy was weeping for his uncle or village association, and they would try to console him. Only the incidents of his later life indicated why Latu wept at that time.

With Sri Ramakrishna

At Ramchandra’s house, Latu heard of Sri Ramakrishna, and naturally he felt eager to see him. And soon opportunities offered themselves to him to go to Dakshineswar and meet the Master. Ramchandra used to send things to the Master through the boy. At the very first meeting, brought about in this way, the Master was greatly impressed with the spiritual potentiality of the boy, and Latu felt immensely drawn to the Master even without knowing anything about his greatness. The pent-up feelings of love of this orphan boy found here an outlet for expression, and he felt so very attached to Sri Ramakrishna that henceforward it was impossible for Latu to do his allotted duties with as much vigour and attention as he could command formerly. All at Ramchandra’s house noticed in him a kind of indifference to everything, but they loved him so much that they did not like to disturb him.

Shortly after Latu’s meeting with the Master, the latter went to Kamarpukur and remained there for about eight months. Latu felt a great void in his heart at this absence of the one whom he loved so much. But he would still go to Dakshineswar now and then and pass some time there, sad and morose. Those who knew him, but could not dive into his mind, thought he had perhaps been reprimanded for some neglect of duty at the house of Ramchandra and had come to ease his mind. For how could they know the great anguish that torments a real devotee’s heart? Latu Maharaj afterwards said, ‘You cannot conceive of the suffering I had at that time. I would go to the Master’s room, wander in the garden, stroll hither and thither. But everything would seem insipid. I would weep alone to unburden my heart. It was only Ram Babu who could to some extent understand my feelings, and he gave me a photograph of the Master.’

When the Master returned from his native village, Latu acquired a new life, as it were, and he would lose no opportunity to go to Dakshineswar to meet him. As Ramchandra would now and then send fruits and sweets to the Master through this boy-servant of his, Latu welcomed and greatly longed for such occasions. Gradually it became impossible for Latu to continue his service. He openly expressed his desire to give up his job and remain at Dakshineswar. The members of Ramchandra’s family would poke fun at him by saying, ‘Who will feed and clothe you at Dakshineswar?’

But with this innocent boy that was not at all a serious problem. The only thing he wanted was to be with the Master. At this time Sri Ramakrishna also felt the necessity of an attendant, And when he proposed the name of Latu to Ramchandra, the latter at once agreed to spare him. Thus Latu got the long-wished-for opportunity of serving Sri Ramakrishna. As a mark of endearment, the Master would call him ‘Leto’, or ‘Neto’. But ‘Latu’ was the name which remained current.

How service to the guru leads to God-realisation is exemplified in the life of Latu Maharaj. He was to Sri Ramakrishna what Hanuman was to Sri Ramachandra. He did not care for anything in the world, his only concern in life was how to serve the Master faithfully. A mere wish of the Master was more than a law—a sacred injunction with Latu. Latu was once found sleeping in the evening. Perhaps he was overtired by the day’s work. The Master mildly reproved Latu for sleeping at such an odd time, saying, ‘If you sleep at such a time, when will you meditate?’ That was enough, and Latu gave up sleeping at night. For the rest of his life, he would have a short nap in the daytime, and the whole night he would pass awake, a living illustration of the verse in the Gita: ‘What is night to the ordinary people is day to the Yogi.’

Unsophisticated as Latu was, he had this great advantage: he would spend all his energy in action and waste no time in vain discussions. Modern minds, the sad outcome of the education they receive, will doubt everything they hear, and therefore discuss, reason, and examine to see if that be true or false. Thus so much energy is lost in arriving at the truth that nothing is left for action. It was just the opposite with Latu. As soon as he heard a word from the Master he rushed headlong to put it into practice. In later life, he would rebuke devotees, who came to him for instruction, by saying, ‘You will simply talk and talk and do nothing. What’s the use of mere discussions?’ Of course Latu was fortunate in having a guru in whose words there was no room for any doubt or discussion and whom it was blessedness to obey and the more implicit that obedience, the greater was the benefit that could be reaped. And Latu was a fit disciple to take the fullest advantage of this rare privilege.

When Latu came to the Master he did not bother much about the spiritual greatness of his guru. He loved him and so he longed to be with him. But the influence of such holy association was sure to have its effect. So there began to come a gradual transformation in the life of Latu. He was fully conscious of his shortcomings, and attributed all his spiritual progress to the Master. One day the Master asked him what God might be doing at the moment. Latu naturally pleaded ignorance. When thereafter the Master remarked that God was passing a camel through the eye of a needle, Latu understood thereby, humility personified as he was, that unfit though he was, God was moulding his life to make him a proper recipient of His grace.

Many incidents are told of Latu’s power of deep meditation. One day he was meditating sitting on the bank of the Ganga. Then there came the flood-tide, and waters surrounded Latu. But he was unconscious of the external world. The news reached the Master, who at once came and brought back his consciousness by loudly calling him. Another day Latu went to meditate in one of the Shiva temples just after noon. But it was almost evening, and still there was no news of Latu. The Master was anxious about him and sent someone to search for him. It was found that Latu was deeply absorbed in meditation and his whole body was wet with perspiration. On hearing this, Sri Ramakrishna came to the temple and began to fan him. After some time Latu returned to the plane of consciousness and felt greatly embarrassed at seeing the Master fanning him. Sri Ramakrishna, however, removed his embarrassment by his sweet and affectionate words. At this time, Latu was day and night in high spiritual moods. With reference to this, the Master himself once remarked, ‘Latu will not come down, as it were, from his ecstatic condition.’

Latu loved Kirtan—congregational songs to the accompaniment of instrumental music and devotional dance. Even while at the house of Ramchandra, if he would see a Kirtan party, he would run to join it, sometimes forgetful of his daily work. When Latu came to Dakshineswar he got greater opportunities to attend the Kirtan parties. On many occasions he would go into ecstasy while singing with them.

A straw best shows which way the wind blows. Sometimes insignificant incidents indicate the direction of the mind of a man. One day Latu, along with others, was playing an indoor game called ‘Golokdham’, which term means the heavenly abode called ‘Golok’ or ‘Goloka’. The point aimed at by each player was that his ‘piece’ should reach ‘Goloka’. In the course of the play, when the ‘piece’ of Latu reached the destination, he was so beside himself with joy that one could see that he felt as if he had actually reached the salvation of life. When Sri Ramakrishna, who was there, saw the great ecstasy of Latu, he remarked that Latu was so happy because in personal life he was greatly eager to attain liberation.

Sri Ramakrishna used to say that frankness is a virtue which one gets as a result of hard tapasya in many previous births; and having frankness, one can expect to realise God very easily. Latu was so very frank that one would wonder at seeing such a childlike trait in him. He would unreservedly speak of his struggle with the flesh to the Master and receive instructions from him.

Once the Master told Latu, ‘Don’t forget Him throughout the day or night.’ And of all forms of spiritual practices it seems Latu laid the greatest stress on repeating the sacred Name. This was also his instruction to others who came to him for guidance in later days. To a devotee who asked him, ‘How can we have self-surrender to God whom we have never seen’, Latu Maharaj said in his inimitable simple way, ‘It does not matter if you do not know Him. You know His name. Just take His name, and you will progress spiritually. What do they do in an office? Without having seen or known the officer, one sends an application addressed to his name. Similarly send your application to God, and you will receive His grace.’

With all his spiritual longing, Latu’s chief endeavour in life was to serve the Master. Once he said in reply to one who questioned him as to how the disciples of the Master got time for worship when they were so much devoted to his service: ‘Well, service to him was our greatest worship and meditation.’

Latu accompanied the Master as a devoted attendant when he was removed for treatment to Shyampukur and thence to Cossipore and served him till the last moment. Latu was one of the chosen twelve to whom the Master gave the gerua cloth as a symbol of detachment. Afterwards when the actual rite for sannyasa was performed and the family name had to be changed, Latu was named Swami Adbhutananda, perhaps because the life of Latu Maharaj was so wonderful—Adbhuta—in every respect.

Spiritual practice at Baranagore

After the passing away of the Master Latu Maharaj accompanied the Holy Mother to Vrindavan and stayed there for a short period. His love and reverence for the Holy Mother was next to that for the Master, if not equal. The Holy Mother also looked upon him exactly as her own child. At Dakshineswar when she had to pass through hard days of work, Latu had been her devoted assistant. Brought up in a village atmosphere, she was very shy and would not talk with anyone outside a limited group. But as Latu was very young and had a childlike attitude towards her, she was free with him. The depth of love and devotion of Latu Maharaj to the Holy Mother throughout his life was amazing and beggars description.

After his return from Vrindavan, he joined the Baranagore monastery. At Baranagore, Latu Maharaj, along with other brother disciples, passed continuously one year and a half in hard spiritual practices, in one or other form of which he would spend the whole night, and in the daytime he would have a short sleep. That became his habit for the whole life. Even if ill, he would sit for meditation in the evening. At Baranagore he was at one time very ill with pneumonia. He was too weak to rise. But he would insist that he should be helped to sit in the evening. When reminded that the doctor had forbidden him to do so, he would show great resentment and say, ‘What does the doctor know? It is his (the Master’s) direction, and it must be done.’ He would be so engrossed in spiritual practices and always so much in spiritual mood that he could not stick to any regular time for food and drink. Because of this characteristic, sometimes food had to be sent to his room at the Baranagore monastery. But on many days the food that was sent in the morning remained untouched till at night. Latu Maharaj had no idea that he had not taken any meal. At night when others retired, Latu Maharaj would lie in his bed feigning sleep. When others were fast asleep, he would quietly rise and tell his beads. Once a funny incident happened on one of such occasions. While Latu Maharaj was telling his beads, a little sound was made. Swami Saradananda thought that a rat had come into the room and he kindled a light to drive it away. At this, all found out the trick that Latu Maharaj was playing on them, and they began to poke fun at him.

Latu Maharaj had his own way of living and he could not conform to the routine life of an institution. Because of this he would afterwards live mostly outside the monastery with occasional short stays at the Alambazar or Belur Math. Swami Vivekananda once made it a rule that everyone should get up in the early hours of the morning, with the ringing of a bell, and meditate. The next day Latu Maharaj was on his way to leave the Math. Swamiji heard the news and asked Latu Maharaj what the matter was with him. Latu Maharaj said, ‘My mind has not reached such a stage that it can with the ringing of your bell be ready for meditation. I shall not be able to sit for meditation at your appointed hours.’ Swamiji understood the whole situation and waived the rule in favour of Latu Maharaj.

Sometimes Latu Maharaj stayed at the house of devotees, sometimes in a room at the Basumati Press belonging to Upendra Nath Mukherjee, a lay disciple of the Master, and very often he lived on the bank of the Ganga without any fixed shelter. The daytime he would pass at one bathing ghat, the night time he would spend at some other ghat with or without any roof. The policeman, who kept watch, came to know him and so would not object to his remaining there at night.

One night, while it was raining, Latu Maharaj took shelter in an empty railway wagon that stood nearby. Soon the engine came and dragged the wagon to a great distance before Latu Maharaj was conscious of what had happened. He then got down and walked back to his accustomed spot. About his food Latu Maharaj was not at all particular. Sometimes a little quantity of gram soaked in water would serve for him the purpose of a meal. He lived on a plane where physical needs do not very much trouble a man, nor can the outside world disturb the internal peace. When asked how he could stay in a room in a printing press where there was so much noise, Latu Maharaj replied that he did not feel much difficulty.

The fact is that the main source of strength of Latu Maharaj was his dependence on the Master. He would always think that the Master would supply him with everything that he needed or was good for him. Later, he would say to those who sought guidance from him, ‘Your dependence on God is so very feeble. If you do not get a result according to your own liking, in two days you give up God and follow your own plan as if you are wiser than He. Real self-surrender means that you will not waver in your faith even in the face of great losses.’ There was nothing in the world which could tempt Latu Maharaj away from his faith in God and the guru.

Wanderings

It is very difficult to trace the chronological events of Latu Maharaj’s life: first because there were no events in his life, except the fact that it was one long stillness of prayer, and secondly because now and then he was out of touch with all. Latu Maharaj made it a point to live within a few miles of Dakshineswar, the great seat of the Master’s sadhana. Rarely did he go further away. In 1895 he once went to Puri; in 1903 he was again at that holy city for about a month; and in the same year he visited some places of Northern India like Varanasi, Allahabad, and Vrindavan. Swamiji took him in his party on his tour in Kashmir and Rajputana. Excepting these occasions Latu Maharaj lived mostly in Calcutta or near about. Latu Maharaj prayed to Jagannath at Puri that he might be vouchsafed two boons— first that he could engage himself in spiritual practices without having a wandering habit and second that he might have a good digestion. When asked why he asked for the second boon which seemed so strange, Latu Maharaj remarked: ‘Well, it is very important in monastic life. There is no knowing what kind of food a monk will get. If he has got a good stomach, he can take any food that chance may bring, and, thus preserving his health, can devote his energy to spiritual practices.’

Towards the end of 1898, when Ramchandra Datta was on his deathbed, Latu Maharaj was by his side. For more than three weeks he incessantly nursed his old master. He took upon himself the main brunt of looking after the patient. With the same earnestness did he nurse the wife of Ramchandra Datta, whom he regarded as his mother, in her dying moments. For about a month or so, with anxious care and unsparingly, Latu Maharaj attended her. It was only when she passed away that he left the house.

Plato and Loren

Though Latu Maharaj was never closely connected with the works of the Ramakrishna Mission, his love for his brother disciples, especially for the leader, whom he would call ‘Loren’ or ‘Loren-bhai’, brother Naren, in his distorted pronunciation, was very great. Latu Maharaj could not identify himself with the works started by Swamiji as they caused distraction to the inner flow of his spiritual life. But he had great faith in one whom the Master praised so much. He used to say, ‘I am ready to take hundreds of births if I can have the companionship of ‘Loren-bhai.’ Swamiji infinitely reciprocated the love of Latu Maharaj. When on his return to Calcutta from the West, he was given a splendid reception and everybody was eager to see and talk with him, Swamiji made anxious inquiry about Latu Maharaj; and when the latter came, he took him by his hand and asked why he had not come for so long. Latu Maharaj with his characteristic frankness said that he was afraid he would be a misfit in the aristocratic company where the Swami was. At this Swamiji very affectionately said, ‘You are ever my Latu-bhai (brother Latu) and I am your Loren-bhai’, and dragged Latu Maharaj with him to take their meals together. The childlike simplicity and open-mindedness of Latu Maharaj made a special appeal to his brother disciples. Sometimes they would poke fun at him taking advantage of his simplicity. But they also had a deep regard for his deep spirituality. Swami Vivekananda used to say, ‘Our Master was original, and everyone of his disciples also is original. Look at Latu. Born and brought up in a poor family, he has attained to a level of spirituality which is the despair of many. We came with education. This was a great advantage. When we felt depressed or life became monotonous, we could try to get inspiration from books. But Latu had no such opportunity for diversion. Yet simply through one-pointed devotion he has made his life exalted. This speaks of his great latent spirituality. Now and then Swamiji would lovingly address Latu Maharaj as ‘Plato’ distorting the name ‘Lato’ as pronounced by the Master, into that famous Greek name bearing indirect testimony to the wisdom the latter had attained. Sometimes the happy relationship between Latu Maharaj and his brother disciples would give rise to very enjoyable situations. Once in Kashmir, Swami Vivekananda, after visiting a temple, remarked that it was two or three thousand years old. At this Latu Maharaj questioned how he could come to such a strange conclusion. Swamiji was in a fix and replied, ‘It is very difficult to explain the reasons for my conclusion to you. It would be possible if you had got modern education.’ Latu Maharaj, instead of feeling abashed at this, said, ‘Well, such is your wisdom that you cannot enlighten an illiterate person like myself.’ The reply threw all into roaring laughter.

Residence at Balaram Bose’s House

In 1903 Latu Maharaj was persuaded to take up his residence at the house of the great devotee Balaram Bose. There he stayed for about nine years till 1912. A very unusual thing for Latu Maharaj! When the request for staying there came to Latu Maharaj, he at first refused on the ground that there was no regularity about his time of taking food and therefore he did not like to inconvenience anyone. But the members of the family earnestly reiterated their request saying that it would be rather a blessing than any inconvenience if he put up at their house and that arrangements would be made so that he might live in any way he liked.

Even at this place where everyone was eager to give him all comforts, Latu Maharaj lived a very stern ascetic life. An eyewitness describes him as he was seen at Balaram Babu’s place: ‘Latu Maharaj was a person of few words. He was also a person of few needs. His room bore witness to it. It lay immediately to the right of the house-entrance. The door was nearly always open, and as one passed, one could see the large empty space with a small thin mat on the floor, at the far end a low table for a bed, on one side a few half-dead embers in an open hearth and on them a pot of tea. I suspect that the pot of tea represented the whole of Latu Maharaj’s concession to the body.’

In this room Latu Maharaj passed the whole day almost alone, absorbed in his own thoughts. Only in the mornings and then evenings he would be found talking with persons who approached him for the solution of their spiritual problems. Outwardly Latu Maharaj was stern and at times he would not reply though asked questions repeatedly. But when in a mood to talk and mix with people, he was amazingly free and sociable. He had not the least trace of egotism in him. Beneath the rough exterior, he hid a very soft heart. Those who were fortunate in having access to that found in him a friend, philosopher, and guide. Even little boys were very free with him. They played with him, scrambled over his shoulders, and found in him a delightful companion. Persons who were lowly and despised found a sympathetic response from his kindly heart. Once asked how he could associate himself with them, he replied, ‘They are at least more sincere.’

Once a man, tipsy with drink, came to him at midnight with some articles of food and requested that Latu Maharaj must accept them, for after that he himself could partake of them as sacramental food. A stern ascetic like Latu Maharaj quietly submitted to the importunities of this vicious character, and the man went away satisfied, all the way singing merry songs. When asked how he could stand that situation, Latu Maharaj said, ‘They want a little sympathy. Why should one grudge that?’

Another day a devotee came to him drenched with rain. Latu Maharaj at once gave him his own clothes to put on. The devotee got alarmed at the very suggestion of wearing the personal clothes of the much revered Latu Maharaj and also because they were ochre clothes, which it was sacrilegious for a layman to put on. But Latu Maharaj persuaded him to wear them as otherwise he might fall ill and fail to attend the office—a very gloomy prospect for a poor man like him.

Latu Maharaj maintained an outward sternness perhaps to protect himself against the intrusion of people. But however stern he might be externally in order to keep off people or however much he might be trying to hide his spiritual fire, people began to be attracted by his wonderful personality. Though he had no academic education whatsoever, he could solve the intricate points of philosophy or the complex problems of spiritual life in such an easy way that one felt he saw the solutions as tangibly as one sees material objects.

Once there came two Western ladies to Latu Maharaj. They belonged to an atheist society. As such, they believed in humanitarian works but not in God. ‘Why should you do good to others?’ asked Latu Maharaj in the course of the conversation with them, ‘Where lies your interest in that? If you don’t believe in the existence of God, there will always remain a flaw in your argument. Humanitarian work is a matter that concerns the good of society. You cannot prove that it will do good to yourself. So after some time you will get tired of doing the work that does not serve your self-interest. On the contrary, if you believe in God there will be a perennial source of interest, for the same God resides in others as in you.’ ‘But can you prove that the one God resides in many?’ asked one of the ladies. ‘Why not?’ came the prompt reply, ‘but it is a subjective experience. Love cannot be explained to another. Only one who loves understands it and also the one who is loved. The same is the case with God. He knows and the one whom He blesses knows. For others He will ever remain an enigma.’

‘How can it be possible that I am the Soul, I being finite and the Soul being infinite?’ asked a devotee. ‘Where is the difficulty?’ replied Latu Maharaj who had the perception of the truth as clear as daylight, ‘Have you not seen jasmine flowers? The petals of those flowers are very small. But even those petals, dew-drops falling on them, reflect the infinite sky. Do they not? In the same way through the grace of God this limited self can reflect the Infinite.’

‘How can an aspirant grasp Brahman which is infinite?’ asked a devotee with a philosophical bent of mind. ‘You have heard music,’ said the monk who was quite innocent of any knowledge of academic philosophy, ‘you have seen how the strings of a Sitar bring out songs. In the same way the life of a devotee expresses Divinity.’

Once, at Baranagore Math, Swami Turiyananda, who had very deep knowledge of scriptures, was saying that God was all kind and was above any sense of hatred or partiality. At this Latu Maharaj ejaculated, ‘Nice indeed! You are defending God as if He is a child.’ ‘If God is not impartial’, said Swami Turiyananda, ‘is He then a despot like the Czar of Russia, doing whatever He likes according to His caprice?’ ‘All right, you may defend your God if you please’, replied Latu Maharaj, ‘but this you should not forget that He is also the power behind the despotism of a Czar.’

Though he had no book-learning, Latu Maharaj could instinctively see the inner significance of scriptures because of his spiritual realisations. Once a pundit was reading the Kathopanishad. When he read the following mantra: ‘The Purusha of the size of a thumb, the inner soul, dwells always in the heart of beings. One should separate Him from the body with patience as the stalk from a grass’, Latu Maharaj was overjoyed and exclaimed, ‘Just the thing,’ as if he was giving out his own inner experience of life.

Though he himself could not read, he liked to hear scriptures read out to him. Once at the dead of night—to him day and night had no difference—he awakened a young monk who slept in his room and asked him to read out the Gita to him. The young monk did so in compliance with his wish.

Mahasamadhi

Latu Maharaj talked of high spiritual things when the mood for that came, but he was too humble to think that he was doing any spiritual good to anybody. Though by coming into contact with him many lives were changed, he did not consciously make any disciple. He used to say that only those persons who were born with a mission like Swami Vivekananda were entitled to make disciples or preach religion. He had a contempt for those who talked or lectured on religion without directing their energies to building up their own character. He used to say that the so-called preachers go out to seek people to listen to them, but if they realise the Truth, people of their own accord would flock around them for spiritual help. Whenever he felt that his words might be interpreted as if he had taken the role of a teacher, he would rebuke himself muttering half-audible words. Thus Latu Maharaj was an unconscious teacher, but the effect of his unintentional teaching was tremendous on the people who came to him.

In 1912 Latu Maharaj went to Varanasi to pass his last days in that holy city. He stayed at various places there. But wherever he lived he radiated the highest spirituality and people circled round him. Even in advanced age he passed the whole night in spiritual practices. Sometimes in the daytime also, when he lay on his bed covered with a sheet and people took him to be sleeping, on careful observation he would be found to be absorbed in his own spiritual thoughts. During the last period of his life, he would not like very much to mix with people. But if he would talk, he would talk only of higher things. He would grow warm with enthusiasm while talking about the Master and Swamiji.

Hard spiritual practices and total indifference to bodily needs told upon his once strong health. The last two or three years of his life he suffered from dyspepsia and various other accompanying ailments. Still he remained as negligent about his health as ever, and one would very often hear him say, ‘It is a great botheration to have a body.’ In the last year of his life he had a blister on his leg which developed gangrene. In the course of the last four days before his passing away, he was daily operated upon twice or thrice. But the wonder of wonders was, he did not show the least indication of any feeling of pain. It was as if the operation was done on some external thing. His mind soared high up, and even the body-idea was forgotten. Later, he would always remain indrawn. As the last moment approached, he became completely self-absorbed. His gaze remained fixed between his brows, and his thoughts were withdrawn from the external world. Wide awake, but oblivious of his surroundings, he stood midway between the conscious and the superconscious planes, till at last the great soul was completely freed from the encagement of the body. Latu Maharaj entered into Mahasamadhi on 24 April 1920.

Those who witnessed the scene say that even after the passing, in his face there was such an expression of calm joy and compassion that they could not distinguish between death and the living state. Everyone was struck by that unique sight. A wonderful life culminated in a wonderful death. Indeed Sri Ramakrishna was a unique alchemist. Out of dust he could create gold. He transformed an orphan boy of lowly birth, wandering in the streets of Calcutta for a means of livelihood, into a saint who commanded the spontaneous veneration of one and all. It is said that when Latu Maharaj passed away, Hindus, Mohammedans—all, irrespective of caste or creed—rushed to pay homage to that great soul. Such was his influence!

Leave a Reply