Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 97:

assaddho akataññū ca sandhicchedo ca yo naro |

hatāvakāso vantāso sa ve uttamaporiso || 97 ||

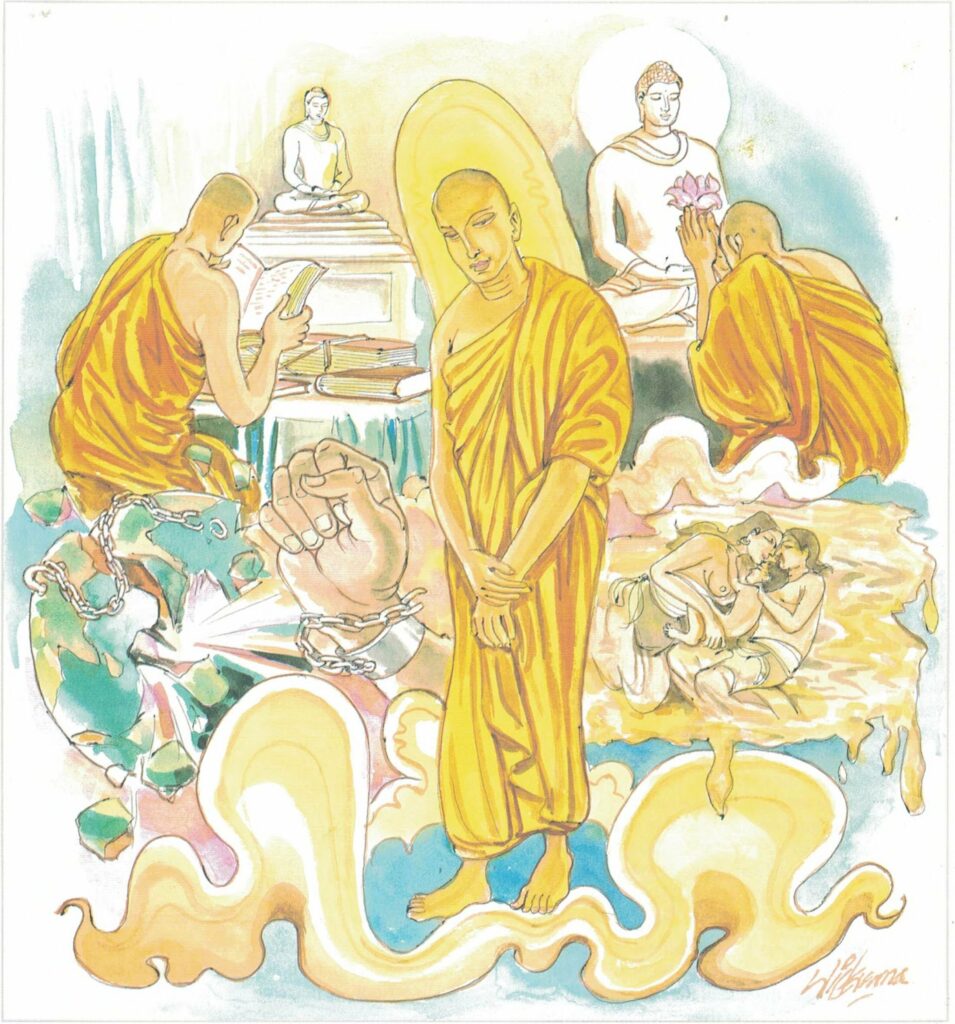

97. With no beliefs, the Unmade known, with fetters finally severed, with kammas cut and cravings shed, attained to humanity’s heights.

The Story of Venerable Sāriputta

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to Venerable Sāriputta.

One day thirty forest-dwellers approached the Buddha, paid obeisance to him, and sat down. The Buddha, seeing that they possessed the requisite faculties for attaining arahatship, addressed Venerable Sāriputta as follows, “Sāriputta, do you believe that the quality of faith, when it has been developed and enlarged, is connected with the deathless and terminates in the deathless?” In this manner the Buddha questioned the Venerable with reference to the five moral qualities.

Said the Venerable, “Venerable, I do not go by faith in the Buddha in this matter, that the quality of faith, when it has been developed and enlarged, is connected with the deathless and terminates in the deathless. But of course, Venerable, those who have not known the deathless or seen or perceived or realized or grasped the deathless by the power of reason, such persons must of necessity go by the faith of others in this matter; namely, that the faculty of faith, when it has been developed and enlarged, is connected with the deathless and terminates in the deathless.” Thus did the Venerable answer his question.

When the monks heard this, they began a discussion: “Venerable Sāriputta has never really given up false views. Even today he refused to believe even the supremely Enlightened One.” When the Buddha heard this, he said, “Monks, why do you say this? For I asked Sāriputta the following question, ‘Sāriputta, do you believe that without developing the five moral qualities, without developing tranquillity and spiritual insight, it is possible for a man to realize the paths and the fruits?’ And he answered me as follows, ‘There is no one who can thus realize the paths and the fruits.’ Then I asked him, ‘Do you not believe that there is such a thing as the ripening of the fruit of almsgiving and good works? Do you not believe in the virtues of the Buddhas and the rest?’ But as a matter of fact, Sāriputta walks not by the faith of others, for the reason that he has, in and by himself, attained states of mind to which the Paths and the Fruits lead, by the power of spiritual insight induced by ecstatic meditation. Therefore he is not open to censure.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 97)

yo naro assaddho akataññū ca sandhicchedo

hatāvakāso vantāso ca, so ve uttamaporiso

yo naro: a person; assaddho [assaddha]: not believing false views; akataññū: aware of nibbāna; ca sandhicchedo [sandhiccheda]: also having severed all connections; hatāvakāso [hatāvakāsa]: having destroyed all the opportunities; vantāso [vantāsa]: having given up all desires; so: he; ve: without any doubt; uttamaporiso [uttamaporisa]: is a noble person

He has no faith in anyone but in himself. He is aware of deathlessness–the unconditioned. He is a breaker of connections, because he has severed all his worldly links. He has destroyed all the opportunities for rebirth. He has given up all desires. Because of all these he–the arahat–is a truly noble person.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 97)

assaddho: non-believer; he so firmly believes his own view and that of the Buddha he does not need to believe in any other.

akataññū: literally, ‘ungrateful’; but, in this context, ‘aware of the unconditioned–that is Nibbāna’.

sandhicchedo: is the term usually given to a burglar, because he breaks into houses. But, here, it signifies severing all worldly connections.

hatāvakāso: a person who has given up all opportunities. But, here it is meant having given up opportunities for rebirth.

Special Note: All the expressions in this stanza can be interpreted as applying to persons who are not noble, but to depraved persons. But, the interpretation of those forms to give positive spiritually wholesome meanings and not negative ones, is quite intriguing. In other words, the Buddha has, in this stanza, used a set of expressions used in general parlance to denote people of mean behaviour. But, due to the implications attributed to them by the Buddha, these depraved terms acquire a high significance.