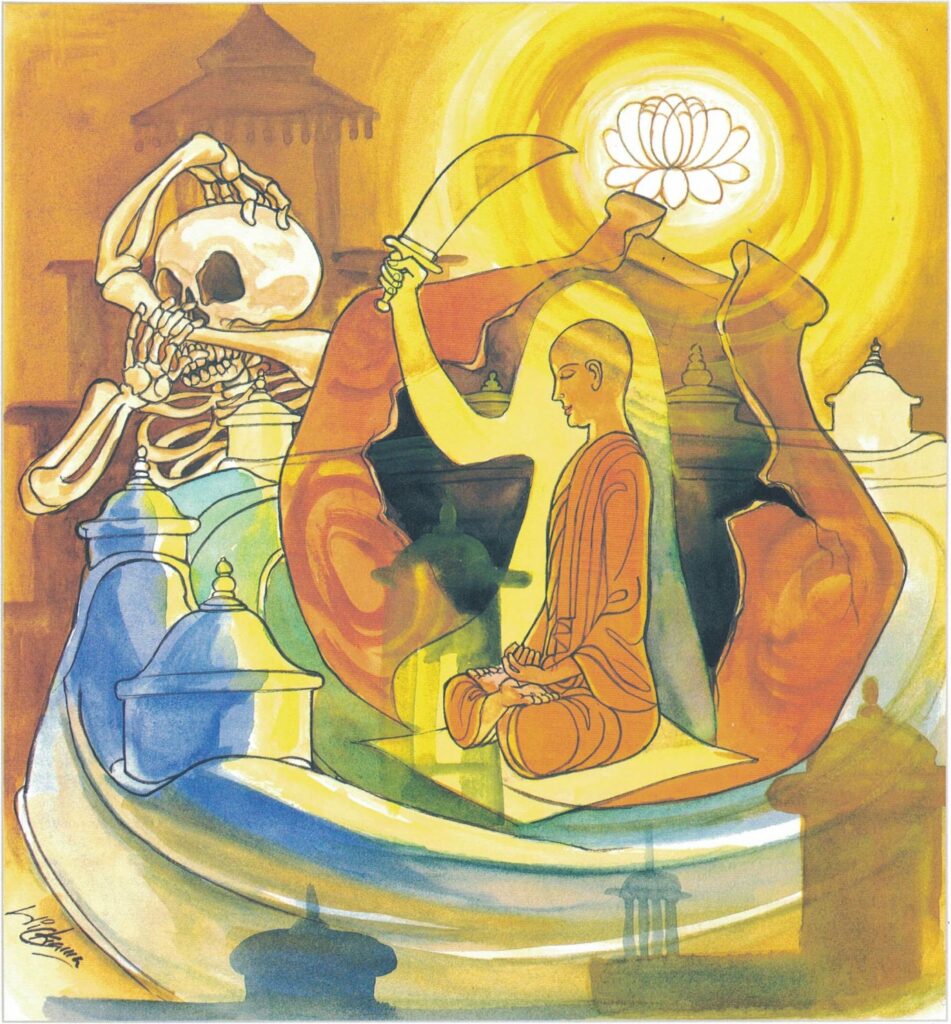

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 40:

kumbhūpamaṃ kāyamimaṃ viditvā nagarūpamaṃ cittamidaṃ ṭhapetvā |

yodhetha māraṃ paññāyudhena jitañca rakkhe anivesano siyā || 40 ||

40. Having known this urn-like body, made firm this mind as fortress town, with wisdom-weapon one fights Māra while guarding booty, unattached.

The Story of Five Hundred Monks

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to five hundred monks.

Five hundred monks from Sāvatthi, after obtaining a meditation topic from the Buddha, travelled for a distance of one hundred leagues away from Sāvatthi and came to a large forest grove, a suitable place for meditation practice. The guardian spirits of the trees dwelling in that forest thought that if those monks were staying in the forest, it would not be proper for them to live with their families. So, they descended from the trees, thinking that the monks would stop there only for one night. But the monks were still there at the end of a fortnight; then it occurred to them that the monks might be staying there till the end of the vassa. In that case, they and their families would have to be living on the ground for a long time. So, they decided to frighten away the monks, by making ghostly sounds and frightful apparitions. They showed up with bodies without heads, and with heads without bodies. The monks were very upset and left the place and returned to the Buddha, to whom they related everything. On hearing their account, the Buddha told them that this had happened because previously they went without any protection and that they should go back there armed with suitable protection.

So saying, the Buddha taught them the protective discourse Metta Sutta at length (Loving-Kindness) beginning with the following stanza:

karanīyamattha kusalena—yaṃ taṃ santaṃ padaṃ abhisamecca

sakko ujū ca sūjū ca—suvaco c’assa mudu anatimāni.“He who is skilled in (acquiring) what is good and beneficial, (mundane as well as supramundane), aspiring to attain perfect peace (Nibbāna) should act (thus): He should be efficient, upright, perfectly upright, compliant, gentle and free from conceit.”

The monks were instructed to recite the sutta from the time they came to the outskirts of the forest grove and to enter the monastery reciting it. The monks returned to the forest grove and did as they were told. The guardian spirits of the trees receiving loving-kindness from the monks reciprocated by welcoming them and not harming them. There were no more ghostly sounds and frightening sights. Thus left in peace, the monks meditated on the body and came to realize its fragile and impermanent nature. From the Jetavana monastery, the Buddha, by his supernormal power, learned about the progress of the monks and sent forth his radiance making them feel his presence. To them he said, “Monks just as you have realized, the body is, indeed, impermanent and fragile like an earthen jar.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 40)

imaṃ kāyaṃ kumbhūpamaṃ viditvā, idaṃ cittaṃ

nagarūpamaṃ ṭhapetvā paññāyudhena māraṃ

yodhetha jitaṃ ca rakkhe anivesano siyā

imaṃ kāyaṃ [kāya]: this body; kumbhūpamaṃ viditvā: viewing as a clay pot; idaṃ cittaṃ [citta]: this mind; nagarūpamaṃ [nagarūpama]: as a protected city; ṭhapetvā: considering; paññāyudhena: with the weapon of wisdom; Māraṃ [Māra]: forces of evil; yodhetha: attack; jitaṃ [jita]: what has been conquered; rakkhe: protect too; anivesano [anivesana]: no seeker of an abode; siyā: be

It is realistic to think of the body as vulnerable, fragile, frail and easily disintegrated. In fact, one must consider it a clay vessel. The mind should be thought of as a city. One has to be perpetually mindful to protect the city. Forces of evil have to be fought with the weapon of wisdom. After the battle, once you have achieved victory, live without being attached to the mortal self.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 40)

kumbhūpamaṃ: compared to an earthen pot. The monks are asked to think of the human body as an earthen pot–fragile, very vulnerable.

cittaṃ nagarūpamaṃ: think of the mind as a guarded citadel. The special quality of the citadel is within it all valuable treasures are stored and guarded. Any outsider can enter and plunder if this is unguarded. It, too, could be attacked by blemishes.

yodhetha Māraṃ paññāyudhena: oppose Māra (evil) with the weapon of wisdom. When forces of evil attack the mind–the city to be guarded–the only weapon for a counter offensive is wisdom, which is a perfect awareness of the nature of things in the real sense.

Give Up the Finite for Infinite

Swami Vivekananda says —

You remember that passage in the sermon of Buddha, how he sent a thought of love towards the south, the north, the east, and the west, above and below, until the whole universe was filled with this lose, so grand, great, and infinite. When you have that feeling, you have true personality. The whole universe is one person; let go the little things. Give up the small for the Infinite, give up small enjoyments for infinite bliss. It is all yours, for the Impersonal includes the Personal. So God is Personal and Impersonal at the same time.

And Man, the Infinite, Impersonal Man, is manifesting Himself as person. We the infinite have limited ourselves, as it were, into small parts. The Vedanta says that Infinity is our true nature; it will never vanish, it will abide for ever. But we are limiting ourselves by our Karma, which like a chain round our necks has dragged us into this limitation. Break that chain and be free. Trample law under your feet. There is no law in human nature, there is no destiny, no fate. How can there be law in infinity? Freedom is its watchword.

Freedom is its nature, its birthright. Be free, and then have any number of personalities you like. Then we will play like the actor who comes upon the stage and plays the part of a beggar. Contrast him with the actual beggar walking in the streets. The scene is, perhaps, the same in both cases, the words are, perhaps, the same, but yet what difference! The one enjoys his beggary while the other is suffering misery from it. And what makes this difference?

The one is free and the other is bound. The actor knows his beggary is not true, but that he has assumed it for play, while the real beggar thinks that it is his too familiar state and that he has to bear it whether he wills it or not. This is the law. So long as we have no knowledge of our real nature, we are beggars, jostled about by every force in nature; and made slaves of by everything in nature; we cry all over the world for help, but help never comes to us; we cry to imaginary beings, and yet it never comes. But still we hope help will come, and thus in weeping, wailing, and hoping, one life is passed, and the same play goes on and on. (Source: Practical Vedanta by Swami Vivekananda)