Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 355:

hananti bhogā dummedhaṃ no ve pāragavesino |

bhogataṇhāya dummedho hanti aññe’va attanaṃ || 355 ||

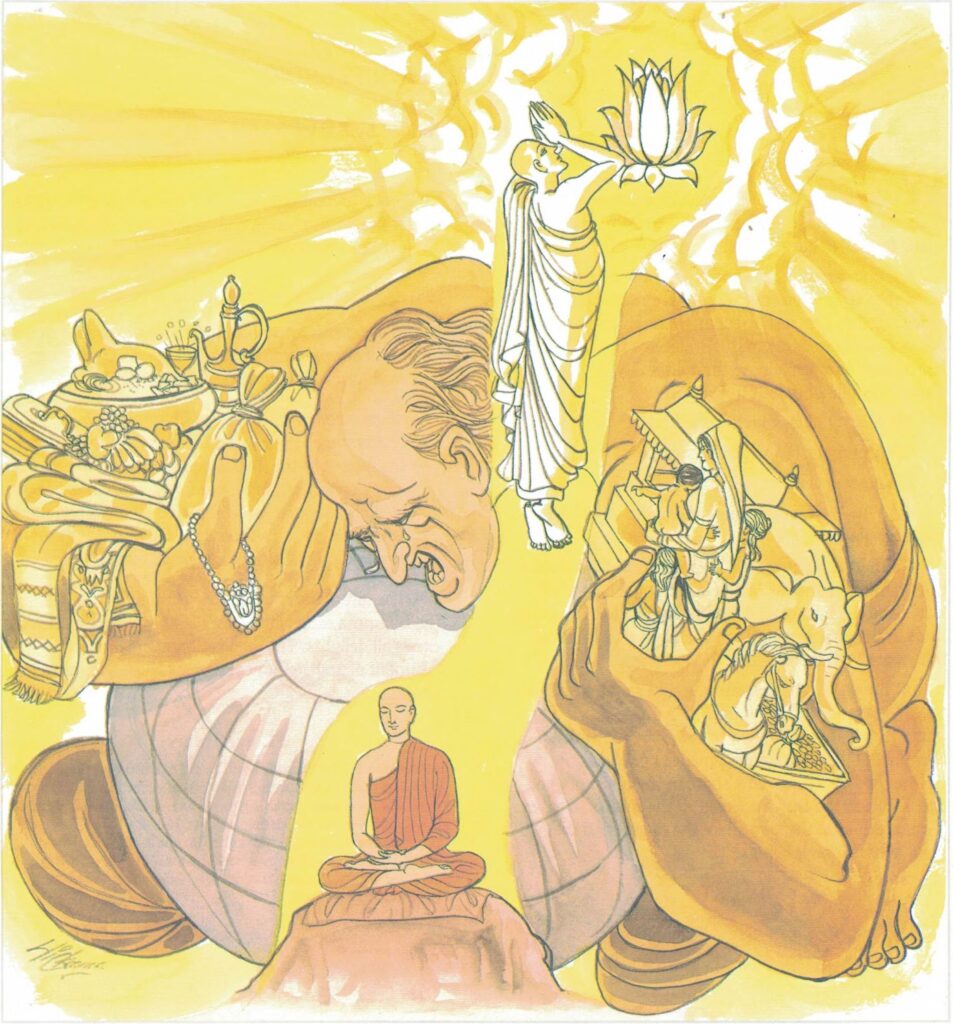

355. Riches ruin a foolish one but not one seeking the Further Shore, craving for wealth a foolish one is ruined as if ruining others.

The Story of a Childless Rich Man

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse with reference to a childless rich man. On one occasion, King Pasenadi of Kosala came to pay homage to the Buddha. He explained to the Buddha that he was late because earlier that day a rich man had died in Sāvatthi without leaving any heirs, and so he had to confiscate all that man’s property. Then, he proceeded to relate about the man who, although very rich, was very stingy. While he lived, he did not give away anything in charity. He was reluctant to spend his money even on himself and, therefore, ate very sparingly and wore only cheap, coarse clothes. On hearing this the Buddha told the king and the audience about the man in a past existence. In that existence also he was a rich man.

One day, when a paccekabuddha (recluse Buddha) came and stood for alms at his house, he told his wife to offer something to the paccekabuddha. His wife thought it was very rarely that her husband gave her permission to give anything to anybody. So, she filled up the alms-bowl with some choice food. The rich man again met the paccekabuddha on his way home and he had a look at the alms-bowl. Seeing that his wife had offered a substantial amount of good food, he thought, “Oh, this monk would only have a good sleep after a good meal. It would have been better if my servants were given such good food; at least, they would have given me better service.” In other words, he regretted that he had asked his wife to offer food to the paccekabuddha. This same man had a brother who also was a rich man. His brother had an only son. Coveting his brother’s wealth, he had killed his young nephew and had thus wrongfully inherited his brother’s wealth on the latter’s death.

Because the man had offered alms-food to the paccekabuddha, he became a rich man in his present life; because he regretted having offered food to the paccekabuddha, he had no wish to spend anything even on himself. Because he had killed his own nephew for the sake of his brother’s wealth he had to suffer in hell for seven existences. His bad kamma having come to an end he was born into the human world but here also he had not gained any good kamma. The king then remarked, “Venerable! Even though he had lived here in the lifetime of the Buddha Himself, he had not made any offering of anything to the Buddha or to his disciples. Indeed, he had missed a very good opportunity; he had been very foolish.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 355)

bhogā dummedhaṃ hananti pāragavesino no ve

dummedho bhogataṇhāya aññe iva attānaṃ hanti

bhogā: wealth; dummedhaṃ [dummedha]: the ignorant; hananti: destroys; pāragavesino [pāragavesina]: those who seek the further shore (truth-seekers questing Nibbāna); no ve: do not destroy; dummedho [dummedha]: the ignorant one; bhogataṇhāya: due to the greed for wealth; aññe iva: as if (destroying) others; attānaṃ [attāna]: one’s own self; hanti: destroys

Wealth destroys the foolish; but it cannot destroy those who seek the other shore (i.e., Nibbāna). By his craving for wealth the fool destroys himself, as he would destroy others.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 355)

paccekabuddha: an independently enlightened one, or separately or individually (=pacceka) enlightened one (renderings as silent or private Buddha, are not very apt). The story that gave rise to this verse refers to paccekabuddhas. Paccekabuddha is a term for an arahat who has realized Nibbāna without having heard the Buddha’s doctrine from others. He comprehends the four noble truths individually (pacceka), independent of any teacher, by his own effort, He has, however, not the capacity to proclaim the Teaching effectively to others, and, therefore, does not become a teacher of gods and men, like a perfect or universal Buddha (sammā-sambuddha). According to tradition, they do not arise in the dispensation of a perfect Buddha; but for achieving perfection after many æons of effort, they have to make this aspiration before a perfect Buddha.

Canonical references are few: they are said to be worthy of a stūpa (dagoba);the treasure-stone Sutta (Nidikhandha Sutta) mentions pacceka-bodhi.