Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 137-140:

yo daṇḍena adaṇḍesu appaduṭṭhesu dussati |

dasannam aññataraṃ ṭhānaṃ khippameva nigacchati || 137 ||

vedanaṃ pharusaṃ jāniṃ sarīrassa ca bhedanaṃ |

garukaṃ vāpi ābādhaṃ cittakkhepaṃ va pāpuṇe || 138 ||

rājato vā upassaggaṃ abbhakkhānaṃ va dāruṇaṃ |

parikkhayaṃ va ñātīnaṃ bhogānaṃ’va pabhaṅguraṃ || 139 ||

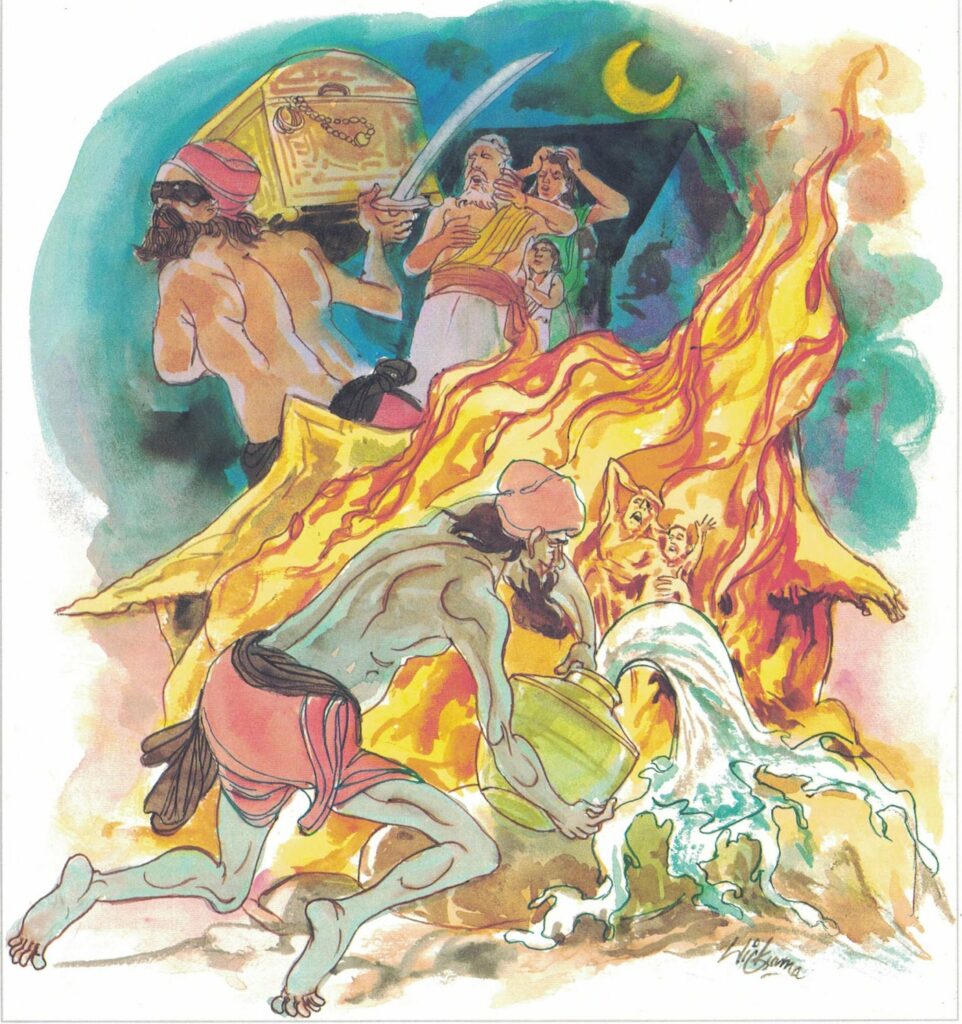

atha v’āssa agārāni aggi ḍahati pāvako |

kāyassa bhedā duppañño nirayaṃ so’upapajjati || 140 ||

137. Whoever forces the forceless or offends the inoffensive, speedily comes indeed to one of these ten states:

138. Sharp pain or deprivation, or injury to the body, or to a serious disease, derangement of the mind;

139. Troubled by the government, or else false accusation, or by the loss of relatives, destruction of one’s wealth;

140. Or one’s houses burn in raging conflagration, at the body’s end, in hell arises that unwise one.

The Story of Venerable Mahā Moggallāna

While residing at the Jītavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to Venerable Mahā Moggallāna. Once upon a time the heretics met together and said to each other, “Brethren, do you know the reason why the gifts and offerings to the Buddha have waxed great?” “No, we do not know; but do you know?” “Indeed we do know; it has all come about through one Venerable Moggallāna. For Venerable Moggallāna goes to heaven and asks the deities what deeds of merit they performed; and then he comes back to earth and says to men, ‘By doing this and that men receive such and such glory.’ Then he goes to hell and asks also those who have been reborn in hell what they did; and comes back to earth and says to men, ‘By doing this and that men experience such and such suffering.’ Men listen to what he says, and bring rich gifts and offerings. Now if we succeed in killing him, all these rich gifts and offerings will fall to us.”

“That is a way indeed!” exclaimed all the heretics. So all the heretics with one accord formed the resolution, “We will kill him by hook or by crook.” Accordingly they roused their own supporters, procured a thousand pieces of money, and formed a plot to kill Venerable Moggallāna. Summoning some wandering thieves, they gave them the thousand pieces of money and said to them, “Venerable Moggallāna lives at Black Rock. Go there and kill him.” The money attracted the thieves and they immediately agreed to do as they were asked. “Yes, indeed,” said the thieves;“we will kill the Venerable.” So they went and surrounded the Venerable’s place of abode.

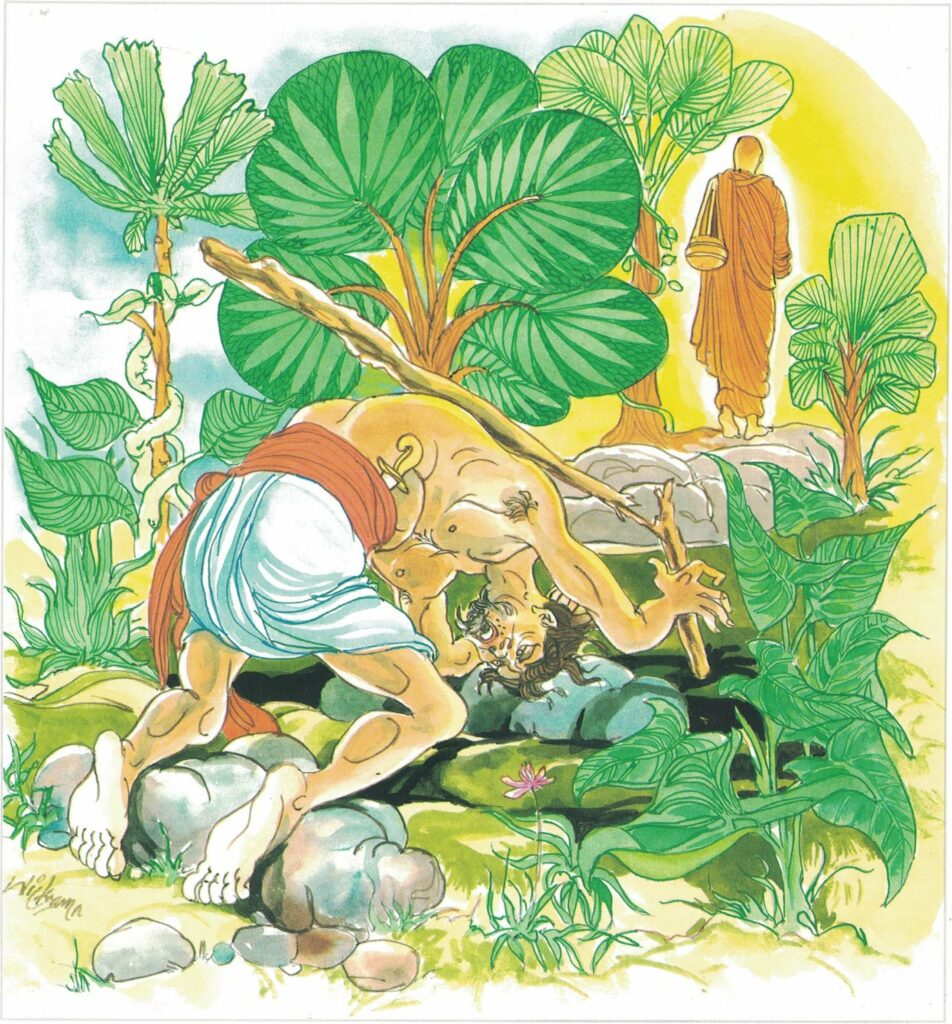

The Venerable, knowing that his place of abode was surrounded, slipped out through the keyhole and escaped. The thieves, not seeing the Venerable that day, came back on the following day, and again surrounded the Venerable’s place of abode. But the Venerable knew, and so he broke through the circular peak of the house and soared away into the air. Thus did the thieves attempt both in the first month and in the second month to catch the Venerable, but without success. But when the third month came, the Venerable felt the compelling force of the evil deed he had himself committed in a previous state of existence, and made no attempt to get away.

At last the thieves succeeded in catching the Venerable. When they had so done, they tore him limb from limb, and pounded his bones until they were as small as grains of rice. Then thinking to themselves, “He is dead,” they tossed his bones behind a certain clump of bushes and went their way. The Venerable thought to himself, “I will pay my respects to the Buddha before I pass into Nibbāna.” Accordingly he swathed himself with meditation as with a cloth, made himself rigid, and soaring through the air, he proceeded to the Buddha, paid obeisance to the Buddha, and said to him, “Venerable, I am about to pass into Nibbāna.” “You are about to pass into Nibbāna, Moggallāna?” “Yes, Venerable.” “To what region of the earth are you going?” “To Black Rock, Venerable.” “Well then, Moggallāna, preach the Law to me before you go, for hereafter I shall have no such disciple as you to look upon.” “That will I do, Venerable,” replied Venerable Moggallāna. So first paying obeisance to the Buddha, he rose into the air, performed all manner of miracles just as did the Venerable Sāriputta on the day when he passed into Nibbāna, preached the Dhamma, paid obeisance to the Buddha, and then went to Black Rock forest and passed into Nibbāna.

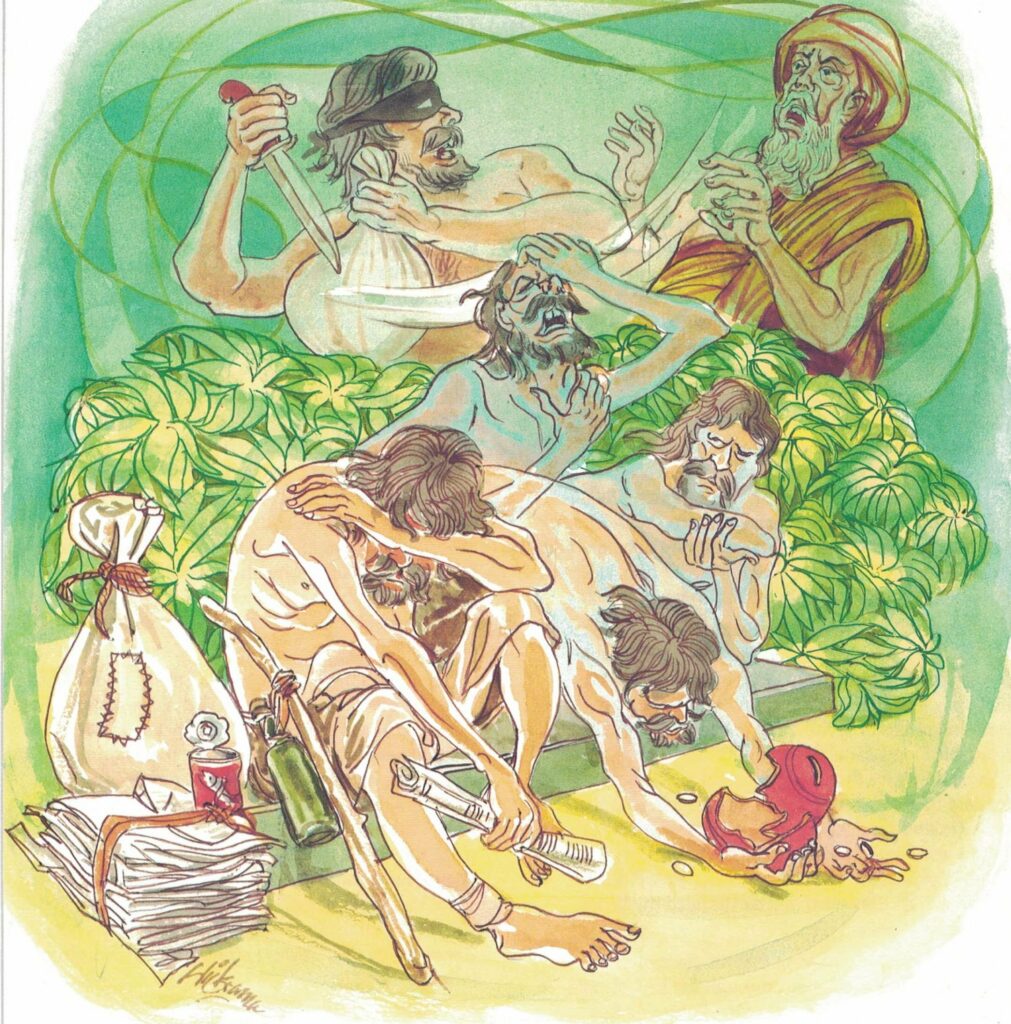

Immediately the report spread all over South Asia. “Thieves have killed the Venerable.” Immediately King Ajātasattu sent out spies to search for the thieves. Now as those very thieves were drinking strong drink in a tavern, one of them struck the other on the back and felled him to the ground. Immediately the second thief reviled the first, saying, “You scoundrel, why did you strike me on the back and fell me to the ground?” “Why, you vagabond of a thief, you were the first to strike Venerable Moggallāna.” “You don’t know whether I struck him or not.” There was a babel of voices crying out, “’Twas I struck him,’Twas I struck him.”

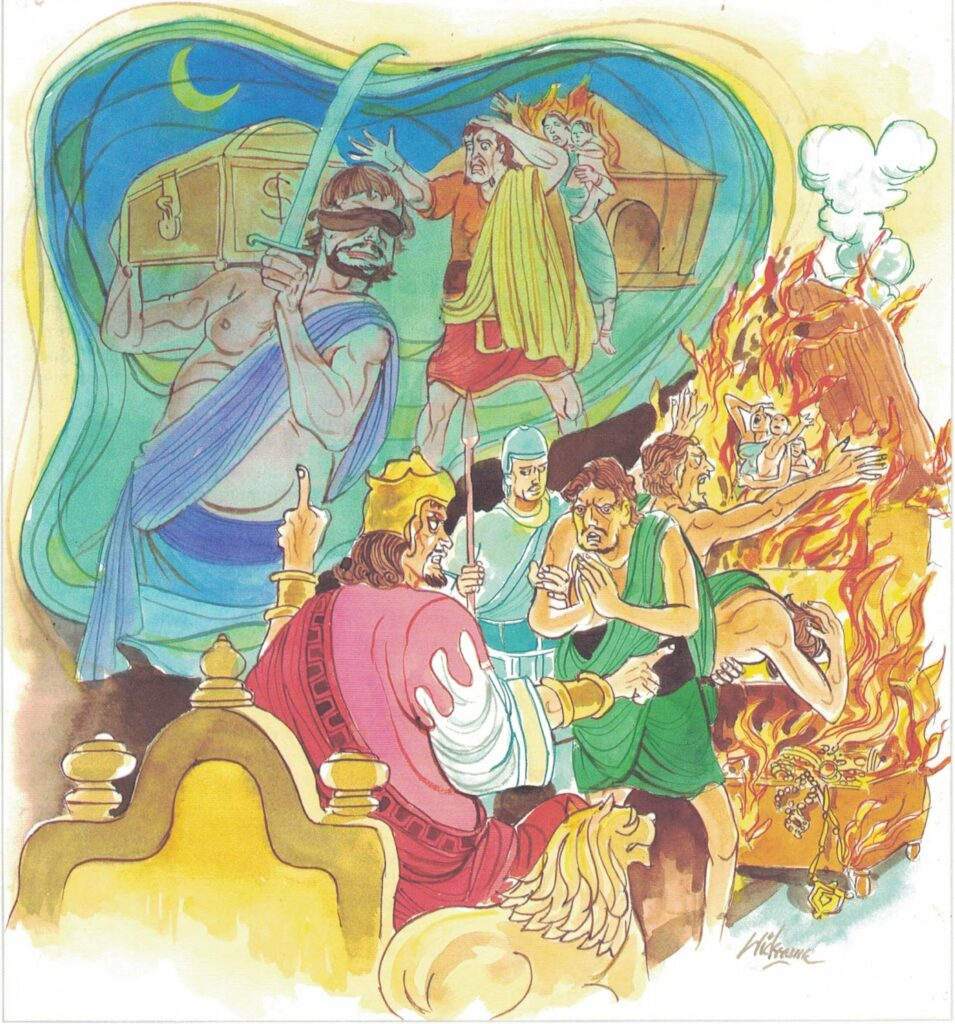

Those spies heard what the thieves said, captured all the thieves, and made their report to the king. The king caused the thieves to be brought into his presence and asked them, “Was it you that killed the Venerable?” “Yes, your majesty.” “Who, pray, put you up to it?” “The naked ascetics, your majesty,” The king had the five hundred naked ascetics caught, placed them, together with the five hundred thieves, waist-deep in pits which he had dug in the palace-court, caused their bodies to be covered over with bundles of straw, and then caused the bundles of straw to be lighted. When he knew that they had been burned, he caused their bodies to be plowed with iron plows and thus caused them all to be ground to bits.

The monks began a discussion in the hall of truth: “Venerable Moggallāna met death which he did not deserve.” At that moment the Buddha approached and asked them, “Monks, what are you saying as you sit here all gathered together?” When they told him, he said, “Monks, if you regard only this present state of existence, Venerable Moggallāna indeed met a death which he did not deserve. But as a matter of fact, the manner of death he met was in exact conformity with the deed he committed in a previous state of existence.” Thereupon the monks asked the Buddha, “But, venerable, what was the deed he committed in a previous state of existence?” In reply the Buddha related his former deed in detail.

The story goes that once upon a time in the distant past a certain youth of good family performed with his own hand all of the household duties, such as pounding rice and cooking, and took care of his mother and father also. One day his mother and father said to him, “Son, you are wearing yourself out by performing all of the work both in the house and in the forest. We will fetch you home a certain young woman to be your wife.” The son replied, “Dear mother and father, there is no necessity of your doing anything of the sort. So long as you both shall live I will wait upon you with my own hand.” In spite of the fact that he refused to listen to their suggestion, they repeated their request time and again, and finally brought him home a young woman to be his wife.

For a few days only she waited upon his mother and father. After those few days had passed, she was unable even to bear the sight of them and said to her husband with a great show of indignation, “It is impossible for me to live any longer in the same house with your mother and father.” But he paid no attention to what she said. So one day, when he was out of the house, she took bits of clay and bark and scum of rice-gruel and scattered them here and there about the house. When her husband returned and asked her what it meant, she said, “This is what your blind old parents have done; they go about littering up the entire house; it is impossible for me to live in the same place with them any longer.” Thus did she speak again and again. The result was that finally even a being so distinguished as he, a being who had fulfilled the Perfection, broke with his mother and father.

“Never mind,” said the husband, I shall find some way of dealing with them properly.” So when he had given them food, he said to them, “Dear mother and father, in such and such a place live kinsfolk of yours who desire you to visit them; let us go thither.” And assisting them to enter a carriage, he set out with them. When he reached the depths of the forest, he said to his father, “Dear father, hold these reins; the oxen know the track so well that they will go without guidance; this is a place where thieves lie in wait for travellers; I am going to descend from the carriage.” And giving the reins into the hands of his father, he descended from the carriage and made his way into the forest.

As he did so, he began to make a noise, increasing the volume of the noise until it sounded as if a band of thieves were about to make an attack. When his mother and father heard the noise, they thought to themselves, “A band of thieves are about to attack us.” Therefore they said to their son, “Son, we are old people; save yourself, and pay no attention to us.” But even as his mother and father cried out thus, the son, yelling the thieves’ yell, beat them and killed them and threw their bodies into the forest. Having so done, he returned home.

When the Buddha had related the foregoing story of Venerable Moggallāna’s misdeed in a previous state of existence, he said, “Monks, by reason of the fact that Venerable Moggallāna committed so monstrous a sin, he suffered torment for numberless hundreds of thousands of years in hell; and thereafter, because the fruit of his evil deed was not yet exhausted, in a hundred successive existences he was beaten and pounded to pieces in like manner and so met death. Therefore the manner of death which Venerable Moggallāna suffered was in exact conformity with his own misdeed in a previous state of existence. Likewise the five hundred heretics who with the five hundred thieves offended against my son who had committed no offense against them, suffered precisely that form of death which they deserved. For he that offends against the offenseless, incurs misfortune and loss through ten circumstances.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 137)

yo adaṇḍesu appaduṭṭhesu daṇḍena dussati

dasannam aññataraṃ ṭhānaṃ khippam eva nigacchati

yo: if a person; adaṇḍesu: the non-violent ones; appaduṭṭhesu: one bereft of evil; daṇḍena: through violence; dussati: hurts; dasannam: (of) ten forms of suffering; aññataraṃ ṭhānaṃ [ṭhāna]: one form of suffering; khippam eva: without delay; nigacchati: will happen

If one attacks one who is harmless, or ill-treats innocent beings, ten woeful states lie here and now to one of which he shall fall.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 138)

pharusaṃ vedanaṃ jāniṃ sarīrassa bhedanaṃ vā

api garukaṃ ābādhaṃ va cittakkhepaṃ va pāpuṇe

pharusaṃ [pharusa]: severe; vedanaṃ [vedana]: pain; jāniṃ [jāni]: disaster; sarīrassa bhedanaṃ [bhedana]: physical damage; vā api: also; garukaṃ ābādhaṃ [ābādha]: serious illness; cittakkhepaṃ [cittakkhepa]: mental disorder; pāpuṇe: will occur

The following ten forms of suffering will come to those who hurt the harmless, inoffensive saints: severe pain; disaster; physical injury; serious illness; mental disorder.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 139)

rājato upassaggaṃ vā dārunaṃ abbhakkhānaṃ vā

ñātīnaṃ parikkhayaṃ vā bhogānaṃ pabhaṅguraṃ vā

rājato [rājata]: from kings; upassaggaṃ vā: trouble; dārunaṃ [dāruna]: grave; abbhakkhānaṃ [abbhakkhāna]: charges; vā ñātīnaṃ [ñātīna]: of relatives; parikkhayaṃ [parikkhaya]: loss; bhogānaṃ pabhaṅguraṃ [pabhaṅgura]: loss of property

Trouble from rulers; grave charges; loss of relatives; property loss.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 140)

atha ivā assa agārāni pāvako aggi ḍahati so

duppañño kāyassa bhedā nirayaṃ upapajjati

atha ivā: or else; assa: his; agārāni pāvako aggi ḍahati: houses the fire will burn; so duppañño [duppañña]: that ignorant person; kāyassa bhedā: on dissolution of the body; nirayaṃ [niraya]: in hell; upapajjati: will be born

Or else, his houses will be burnt by fire and, upon death, that wicked person will be reborn in hell.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 137-140)

Venerable Moggallāna: These four stanzas relate to the demise, under tragic circumstances, of the Chief Disciple Moggallāna. If Sāriputta could be regarded as the Chief Disciple on the right of Buddha, Moggallāna was the Chief Disciple on His left. They were born on the same day and were associated with each other during many previous lives; so were they during the last life. It is one of the oldest recorded friendships in the world. Venerable Moggallāna was foremost in the noble Sangha in psychic power. Once a king of cobras called Nandopananda, also noted for psychic feats, was threatening the Buddha and some arahats. The Buddha was besieged with offers from various members of the noble sangha to subdue the snake king. At last Venerable Moggallāna’s turn came and the Buddha readily assented. He knew he was equal to the task The result was a psychic confrontation with the Naga King who was worsted and he begged for peace. The Buddha was present throughout the encounter.

This epic feat is commemorated in the seventh verse of the Jayamangala Gāthā which is recited at almost every Buddhist function. Whether in shaking the marble palace of Sakka, the heavenly ruler, with his great toe, or visiting hell, he was equally at ease. These visits enabled him to be a sort of an information bureau. He could graphically narrate, to dwellers of this earth, the fate of their erstwhile friends or relatives. How, by evil Kamma, some get an ignominious rebirth in hell, and others, by good Kamma, an auspicious rebirth in one of the six heavens. These ministrations brought great fame to the dispensation, much to the chagrin of other sects. His life is an example and a grim warning. Even a chief disciple, capable of such heroic feats, was not immune from the residue of evil kamma sown in the very remote past. It was a heinous crime. He had committed matricide and patricide under the most revolting circumstances. Many rebirths in hell could not adequately erase the evil effects of the dire deed. Long ago, to oblige his young wife, whose one obsession was to get rid of her parents-in-law, he took his aged parents to a forest, as if going on a journey, waylaid and clubbed them to death, amidst cries of the parents imploring the son to escape from the robbers, who they imagined were clubbing them. In the face of such cruelty, the love of his parents was most touching. In the last life of Moggallāna, he could not escape the relentless force of kamma. For, with an arahat’s parinibbāna, good or bad effects of kamma come to an end. He was trapped twice by robbers but he made good his escape. But, on the third occasion, he saw with his divine eye, the futility of escape. He was mercilessly beaten, so much so that his body could be put even in a sack. But death must await his destiny. It is written that a chief disciple must not only predecease the Buddha, but also had to treat the Buddha before his death (parinibbāna), and perform miraculous feats and speak verses in farewell, and the Buddha had to enumerate his virtues in return. He was no exception. The curtain came down closing a celebrated career.

The noble Sangha was bereft of the most dynamic figure. Chief Disciple Moggallāna’s life story is intimately linked with that of co-Chief Disciple Sāriputta.

Not far from Rājagaha, in the village Upatissa, also known as Nālaka, there lived a very intelligent youth named Sāriputta. Since he belonged to the leading family of the village, he was also called Upatissa. Though nurtured in Brāhmanism, his broad outlook on life and matured wisdom compelled him to renounce his ancestral religion for the more tolerant and scientific teachings of the Buddha Gotama. His brothers and sisters followed his noble example. His father, Vanganta, apparently adhered to the Brāhmin faith. His mother, who was displeased with the son for having become a Buddhist, was converted to Buddhism by himself at the moment of his death.

Upatissa was brought up in the lap of luxury. He found a very intimate friend in Kolita, also known as Moggallāna, with whom he was closely associated from a remote past. One day, as both of them were enjoying a hill-top festival, they realized how vain, how transient, were all sensual pleasures. Instantly they decided to leave the world and seek the path of release. They wandered from place to place in quest of peace.

The two young seekers went at first to Sanjaya, who had a large following, and sought ordination under him. Before long, they acquired the meager knowledge which their master imparted to them, but dissatisfied with his teachings, as they could not find a remedy for that universal ailment with which humanity is assailed–they left him and wandered hither and thither in search of peace. They approached many a famous brāhmin and ascetic, but disappointment met them everywhere. Ultimately, they returned to their own village and agreed amongst themselves that, whoever would first discover the Path should inform the other.

It was at that time that the Buddha dispatched His first sixty disciples to proclaim the sublime Dhamma to the world. The Buddha Himself proceeded towards Uruvela, and the Venerable Assajī, one of the first five disciples, went in the direction of Rājagaha.

The good kamma of the seekers now intervened, as if watching with sympathetic eyes their spiritual progress. For Upatissa, while wandering in the city of Rājagaha, casually met an ascetic whose venerable appearance and saintly deportment at once arrested his attention. This ascetic’s eyes were lowly fixed a yoke’s distance from him, and his calm face showed deep peace within him. With body well composed, robes neatly arranged, this venerable figure passed with measured steps from door to door, accepting the morsels of food which the charitable placed in his bowl. “Never before have I seen,” he thought to himself, “an ascetic like this. Surely, he must be one of those who have attained arahatship, or one who is practicing the path leading to arahatship. How if I were to approach him and question, ‘For whose sake, Sire, have you retired from the world? Who is your teacher? Whose doctrine do you profess?’”

Upatissa, however, refrained from questioning him, as he thought he would thereby interfere with his silent begging tour. The Arahat Assajī, having obtained what little he needed, was seeking a suitable place to eat his meal. Upatissa seeing this, gladly availed himself of the opportunity to offer him his own stool and water from his own pot. Fulfilling thus the preliminary duties of a pupil, he exchanged pleasant greetings with him, and reverently inquired, “Venerable, calm and serene are your organs of sense, clean and clear is the hue of your skin. For whose sake have you retired from the world? Who is your teacher? Whose doctrine do you profess?” The unassuming Arahat Assajī modestly replied, as is the characteristic of all great men, “I am still young in the sangha, brother, and I am not able to expound the Dhamma to you at length.”

“I am Upatissa, Venerable. Say much or little according to your ability, and it is left to me to understand it in a hundred or thousand ways.”

“Say little or much,” Upatissa continued, “tell me just the substance. The substance only do I require. A mere jumble of words is of no avail.”

The Venerable Assajī spoke a four line stanza, thus skillfully summing up the profound philosophy of the Master, on the truth of the law of cause and effect.

Ye dhammā hetuppabhavā

tesaṃ hetuṃ tathāgato

Aha tesañ ca yo nirodho

evaṃ vādi mahā samano.(Of things that proceed from a cause, their cause the Buddha has told, and also their cessation. Thus teaches the great ascetic.)

Upatissa was sufficiently enlightened to comprehend such a lofty teaching succinctly expressed. He was only in need of a slight indication to discover the truth. So well did the Venerable Assajī guided him on his upward path that immediately on hearing the first two lines, he attained the first stage of sainthood, sotāpatti. The new convert Upatissa must have been, no doubt, destitute of words to thank to his heart’s content his Venerable teacher for introducing him to the sublime teachings of the Buddha. He expressed his deep indebtedness for his brilliant exposition of the truth, and obtaining from him the necessary particulars with regard to the master, took his leave. Later, the devotion showed towards his teacher was such that since he heard the Dhamma from the Venerable Assajī, in whatever quarter he heard that his teacher was residing, in that direction he would extend his clasped hands in an attitude of reverent obeisance and in that direction he would turn his head when he lay down to sleep.

Now, in accordance with the agreement he returned to his companion Kolita to convey the joyful tidings. Kolita, who was as enlightened as his friend, also attained the first stage of Sainthood on hearing the whole stanza. Overwhelmed with joy at their successful search after peace, as in duty bound, they went to meet their teacher Sanjaya with the object of converting him to the new doctrine. Frustrated in their attempt Upatissa and Kolita, accompanied by many followers of Sanjaya who readily joined them, repaired to the Veluvana Monastery to visit their illustrious Teacher, the Buddha.

In compliance with their request, the Buddha admitted both of them into the sangha by the mere utterance of the words–Etha Bhikkhave! (Come, O Monks!). A fortnight later, the Venerable Sāriputta attained arahatship on hearing the Buddha expound the Vedanā Pariggaha Sutta to the wandering ascetic Dīghanakha. On the very same day in the evening, the Buddha gathered round Him His disciples, and the exalted positions of the first and second disciples in the Sangha, were respectively conferred upon the Venerables Upatissa (Sāriputta) and Kolita (Moggallāna), who also had attained arahatship a week earlier.