Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 113:

yo ca vassasataṃ jīve apassaṃ udayavyayaṃ |

ekā’haṃ jīvitaṃ seyyo passato udayavyayaṃ || 113 ||

113. Though one should live a hundred years not seeing rise and fall, yet better is life for a single day seeing rise and fall.

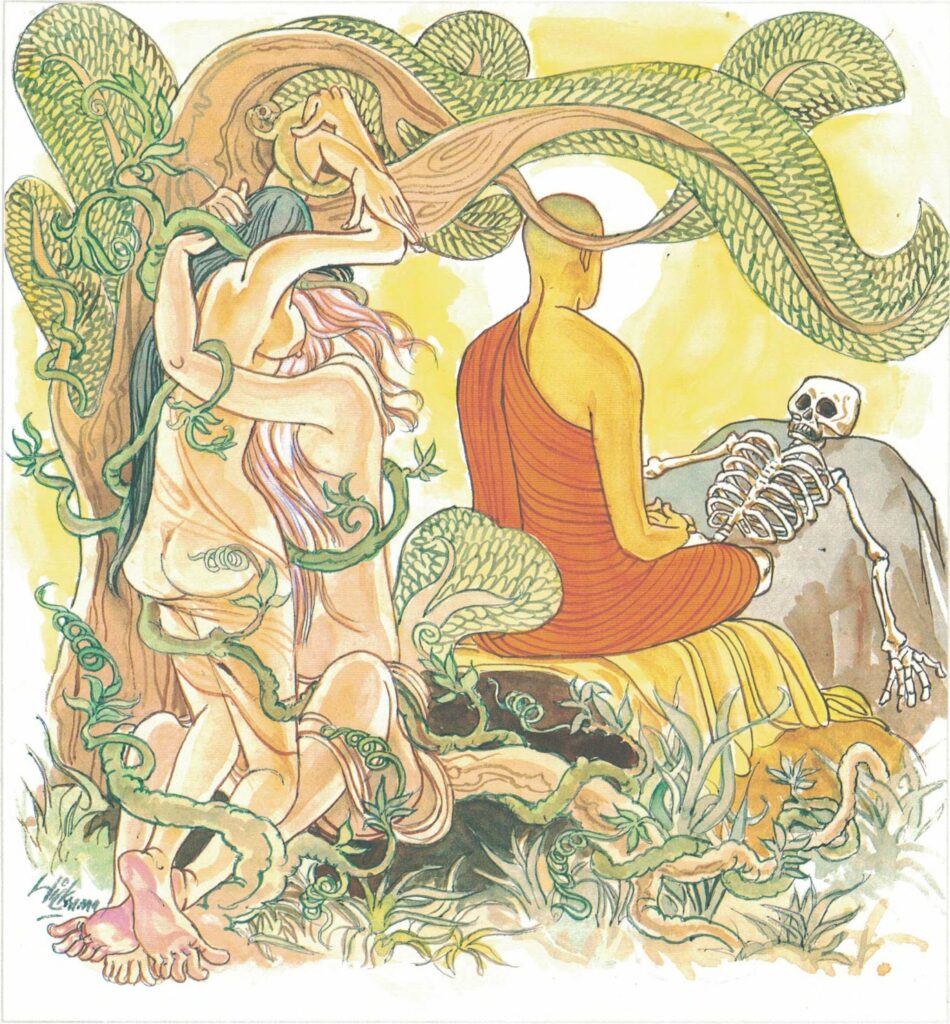

The Story of Nun Patācārā

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to Patācārā.

Patācārā was the daughter of a rich man from Sāvatthi. She was very beautiful and was guarded very strictly by her parents. But one day, she eloped with a young male attendant of the family and went to live in a village, as a poor man’s wife. In due course she became pregnant and as the time for confinement drew near, she asked permission from her husband to return to her parents in Sāvatthi, but her husband discouraged her. So, one day, while her husband was away, she set out for the home of her parents. He followed her and caught up with her on the way and pleaded with her to return with him; but she refused. It so happened that as her time was drawing so near, she had to give birth to a son in one of the bushes. After the birth of her son she returned home with her husband.

Then, she was again with child and as the time for confinement drew near, taking her son with her, she again set out for the home of her parents in Sāvatthi. Her husband followed her and caught up with her on the way; but her time for delivery was coming on very fast and it was also raining hard. The husband looked for a suitable place for confinement and while he was clearing a little patch of land, he was bitten by a poisonous snake, and died instantaneously. Patācārā waited for her husband, and while waiting for his return she gave birth to her second son. In the morning, she searched for her husband, but only found his dead body. Saying to herself that her husband died on account of her, she continued on her way to her parents. Because it had rained incessantly the whole night, the Aciravati River was in spate; so it was not possible for her to cross the river carrying both her sons. Leaving the elder boy on this side of the river, she crossed the stream with her day-old son and left him on the other bank. She then came back for the elder boy. While she was still in the middle of the river, a large hawk hovered over the younger child taking it for a piece of meat. She shouted to frighten away the bird, but it was all in vain;the child was carried away by the hawk. Meanwhile, the elder boy heard his mother shouting from the middle of the stream and thought she was calling out to him to come to her. So he entered the stream to go to his mother, and was carried away by the strong current. Thus Patācārā lost her two sons as well as her husband. So she wept and lamented loudly, “A son is carried away by a hawk, another son is carried away by the current, my husband is also dead, bitten by a poisonous snake!” Then, she saw a man from Sāvatthi and she tearfully asked after her parents. The man replied that due to a violent storm in Sāvatthi the previous night, the house of her parents had fallen down and that both her parents, together with her three brothers, had died, and had been cremated on one funeral pyre. On hearing this tragic news, Patācārā went stark mad. She did not even notice that her clothes had fallen off from her and that she was half-naked. She went about the streets, shouting out, “Woe is me!”

While the Buddha was giving a discourse at the Jetavana Monastery, he saw Patācārā at a distance; so he willed that she should come to the congregation. The crowd seeing her coming tried to stop her, saying “Don’t let the mad woman come in.” But the Buddha told them not to prevent her coming in. When Patācārā was close enough to hear him, he told her to be careful and to keep calm. Then, she realized that she did not have her skirt on and shamefacedly sat down. Someone gave her a piece of cloth and she wrapped herself up in it. She then told the Buddha how she had lost her sons, her husband, her brothers and her parents. She later became a nun and attained liberation.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 113)

udayabbayaṃ apassaṃ yo ca vassasataṃ jīve (tato)

udayabbayaṃ passato kusīto hīnavīriyo ekāhaṃ jīvitaṃ seyyo

udayabbayaṃ [udayabbaya]: the rise and decline; apassaṃ [apassa]: does not see; yo ca: an individual; vassasataṃ [vassasata]: a hundred years; jīve: were to live; udayabbayaṃ [udayabbaya]: the arising and disappearance; passato [passata]: he who sees; ekāhaṃ [ekāha]: even one day’s; jīvitaṃ [jīvita]: life; seyyo [seyya]: is noble

A single day’s life of a person who perceives the arising and the disappearance of things experienced is nobler and greater than the hundred-year life-span of a person who does not perceive the process of the arising and the disappearance of things.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 113)

udayabbayaṃ: the coming into being of the five-fold totality of experience (panca khanda): (1) form; (2) sensation; (3) perception; (4) conception and (5) cognition.