Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 296-301:

suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti sadā gotamasāvakā |

yesaṃ divā ca ratto ca niccaṃ buddhagatā sati || 296 ||

suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti sadā gotamasāvakā |

yesaṃ divā ca ratto ca niccaṃ dhammagatā sati || 297 ||

suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti sadā gotamasāvakā |

yesaṃ divā ca ratto ca niccaṃ saṅghagatā sati || 298 ||

suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti sadā gotamasāvakā |

yesaṃ divā ca ratto ca niccaṃ kāyagatā sati || 299 ||

suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti sadā gotamasāvakā |

yesaṃ divā ca ratto ca ahiṃsāya rato mano || 300 ||

suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti sadā gotamasāvakā |

yesaṃ divā ca ratto ca bhāvanāya rato mano || 301 ||

296. Well awakened, they’re awake ever the Buddha’s pupils who constantly by day, by night are mindful of the Buddha.

297. Well awakened, they’re awake ever the Buddha’s pupils who constantly by day, by night are mindful of the Dhamma.

298. Well awakened, they’re awake ever the Buddha’s pupils who constantly by day, by night are mindful of the Sangha.

299. Well awakened, they’re awake ever the Buddha’s pupils who constantly by day, by night are mindful of the body.

300. Well awakened, they’re awake ever the Buddha’s pupils who constantly by day, by night in harmlessness delight.

301. Well awakened, they’re awake ever the Buddha’s pupils who constantly by day, by night in meditation take delight.

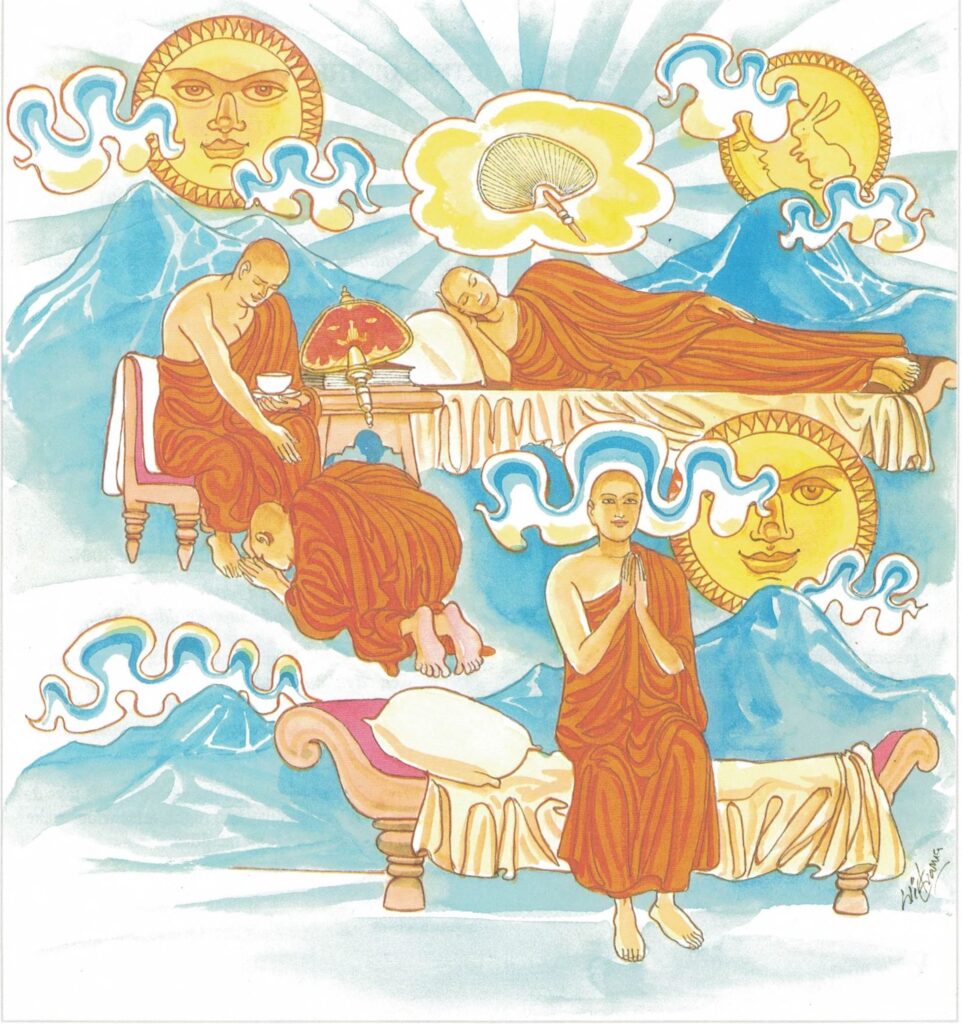

The Story of a Wood Cutter’s Son

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to the son of a wood cutter.

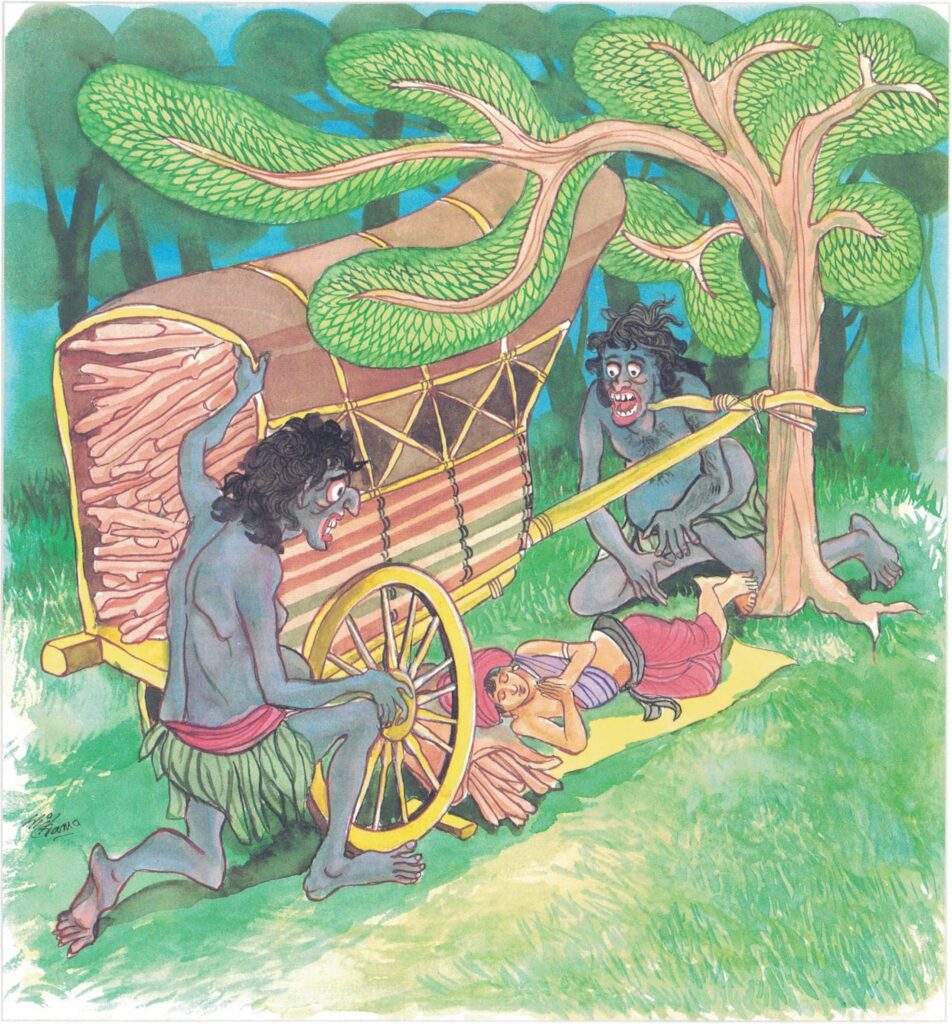

Once, in Rājagaha, a wood cutter went into the woods with his son to cut some firewood. On their return home in the evening, they stopped near a cemetery to have their meal. They also took off the yoke from the two oxen to enable them to graze nearby; but the two oxen went away without being noticed by them. As soon as they discovered that the oxen were missing, the wood cutter went to look for them, leaving his son with the cart of firewood. The father entered the town, looking for his oxen. When he went to return to his son it was getting late and the city gate was closed. Therefore, the young boy had to spend the night alone underneath his cart.

The wood cutter’s son, though young, was always mindful and was in the habit of contemplating the unique qualities of the Buddha. That night, two evil spirits came to frighten and to harm him. When one of the evil spirits pulled at the leg of the boy, he cried out, “I pay homage to the Buddha” (Namo Buddhassa). Hearing those words, the evil spirits got frightened and felt that they must look after the boy. So one of them remained near the boy, guarding him from all dangers; the other went to the king’s palace and brought the food tray of King Bimbisāra. The two evil spirits then fed the boy as if he were their own son. At the palace, the evil spirit left a written message concerning the royal food tray; and this message was visible only to the king.

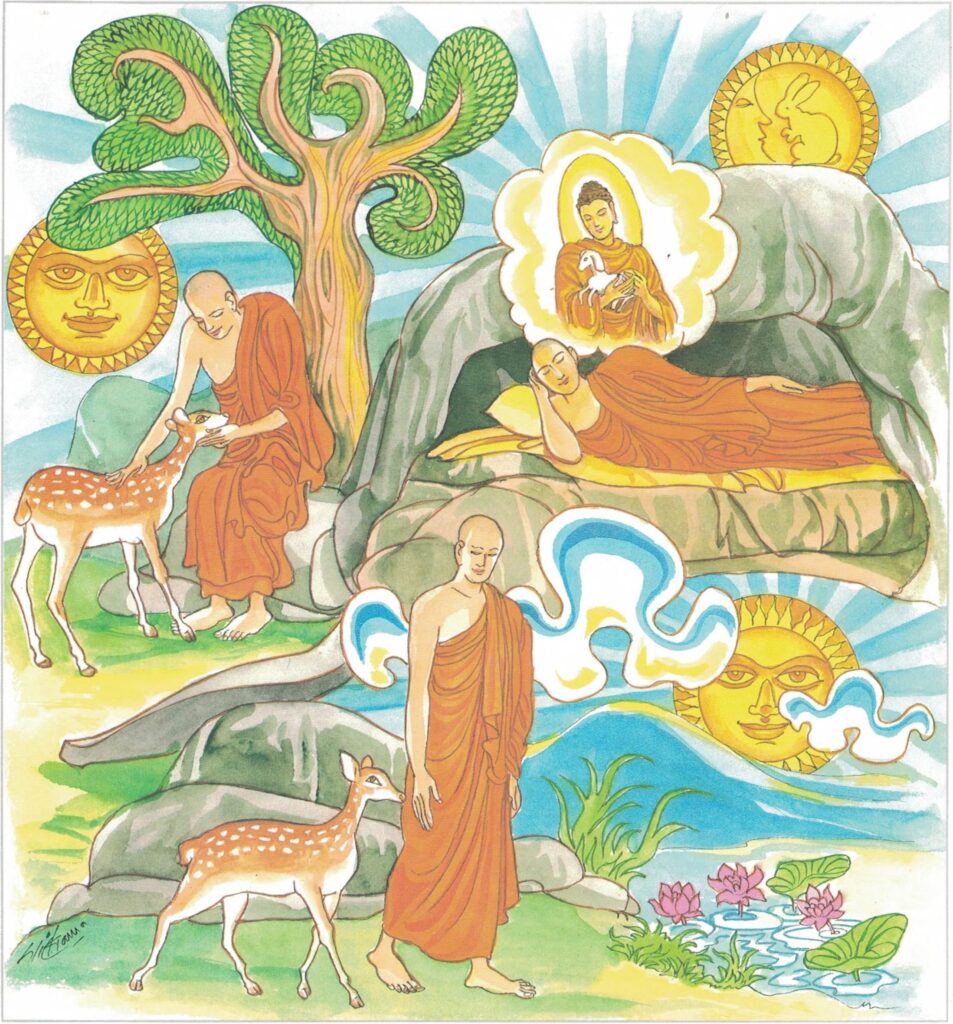

In the morning, the king’s men discovered that the royal food tray was missing and they were very upset and very much frightened. The king found the message left by the evil spirit and directed his men where to look for it. The king’s men found the royal food tray among the firewood in the cart. They also found the boy who was still sleeping underneath the cart. When questioned, the boy answered that his parents came to feed him in the night and that he went to sleep contentedly and without fear after taking his food. The boy knew only that much and nothing more. The king sent for the parents of the boy, and took the boy and his parents to the Buddha. The king, by that time, had heard that the boy was always mindful of the unique qualities of the Buddha and also that he had cried out “Namo Buddhassa” when the evil spirit pulled at his leg in the night.

The king asked the Buddha, “Is mindfulness of the unique qualities of the Buddha the only dhamma that gives one protection against evil and danger, or is mindfulness of the unique qualities of the Dhamma equally potent and powerful?” To him, the Buddha replied, “O king, my disciple! There are six things, mindfulness of which is a good protection against evil and danger.”

Then the Buddha gave a discourse.

At the end of the discourse, the boy and his parents attained sotāpatti fruition. Later, they joined the Sangha and eventually they became arahats.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 296)

yesaṃ divā ca ratto ca niccaṃ Buddhagatāsati

gotamasāvakā sadā suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti

yesaṃ [yesa]: if someone; divā ca: during day; ca ratto [ratta]: and at night; niccaṃ [nicca]: constantly; Buddhagatāsati: practice the Buddha-mindfulness; Gotamasāvakā: those disciples of the Buddha; sadā: always; suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti: arise, well awake

Those disciples of the Buddha who are mindful of the virtues of their Teacher day and night, arise wide awake and in full control of their faculties.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 297)

yesaṃ divā ca ratto ca niccaṃ dhammagatā sati

gotamasāvakā sadā suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti

yesaṃ [yesa]: if someone; divā ca: during day; ca ratto [ratta]: and at night; niccaṃ [nicca]: constantly; Dhammagatā sati: practises the dhamma-mindfulness; Gotamasāvakā: those disciples of the Buddha; sadā: always; suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti: arise, well-awake

Those disciples of the Buddha who are mindful of the virtues of the Dhamma day and night, arise wide awake and in full control of their faculties.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 298)

yesaṃ divā ca ratto ca niccaṃ saṅghagatā

sati sadā suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti

yesaṃ [yesa]: if someone; divā ca: during day; ca ratto [ratta]: and at night; niccaṃ [nicca]: constantly; Saṅghagatā sati: practises the Sangha-mindfulness; Gotamasāvakā: those disciples of the Buddha; sadā: always; suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti: arise, well-awake

The disciples of the Buddha who are mindful of the virtues of the Saṅgha–the brotherhood–day and night, arise wide awake and in full control of their faculties.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 299)

yesaṃ divā ca ratto ca niccaṃ kāyagatā sati

gotamasāvakā sadā suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti

yesaṃ [yesa]: if someone; divā ca: during day; ca ratto [ratta]: and at night; niccaṃ [nicca]: constantly; kāyagatā sati: practises the meditation with regard to physical reality; Gotamasāvakā: those disciples of the Buddha; sadā: always; suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti: arise, well-awake

The disciples of the Buddha who are mindful of the real nature of the body day and night, arise wide awake and in full control of their faculties.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 300)

yesaṃ mano divā ca ratto ca ahimsāya rato

gotamasāvakā sadā suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti

yesaṃ mano: if someone’s mind; divā ca: during day; ca ratto [ratta]: and at night; ahimsāya: in harmlessness; rato delights; Gotamasāvakā: those disciples of the Buddha; sadā: always; suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti: arise, wellawake

The disciples of the Buddha whose minds take delight in harmlessness day and night, arise wide awake and in full control of their faculties.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 301)

yesaṃ mano divā ca ratto ca bhāvanāya rato

gotamasāvakā sadā suppabuddhaṃ pabujjhanti

yesaṃ [yesa]: if someone’s; mano: mind; divā ca ratto ca: day and night; bhāvanāya: in meditation; rato: delights; Gotamasāvakā: those disciples of the Buddha; sadā: always; suppabuddhaṃ [suppabuddha]: wide awake; pabujjhanti: arise

The disciples of the Buddha whose minds take delight in meditation day and night, arise wide awake and in full control of their faculties.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 296-301)

buddhānussati bhāvanā: This form of meditation is suitable to be practiced by everyone both young and old. The word anussati means reflection. Therefore buddhānussati bhāvanā means the meditation practiced while reflecting on the virtues of the Buddha.

The Buddha has infinite virtues. But these are incorporated in nine main virtues. They are called the ninefold virtues of the Buddha enumerated as Itipiso bhagavā… Buddhānussati bhāvanā has to be practiced while reflecting on these virtues.

It is difficult to meditate while reflecting on all the virtues of the Buddha at the same time. Therefore, it is much easier to reflect on one out of many such virtues. Later one could practice meditation, reflecting on all the virtues. One could start with the first virtue, namely arahat, and proceed in the following manner:

Firstly, one should clean oneself and worship the Triple Gem with offerings of flowers and then seek the three-fold refuge and observe the five precepts. Thereafter, seated in a convenient posture before a statue of the Buddha, one should strive to create the image of the Buddha in one’s own mind by looking at it with love and adoration. Then closing the eyes and placing the right hand on the left, one should think thus while being cognizant of the fact that the Buddha is present in one’s mind.

(1) The Lord Buddha does not commit any sin whatsoever even in secret. Therefore he is called Arahat.

(2) One should continue to think in this manner for sometime. Thereafter one should meditate thus: The Buddha does not commit any sin whatsoever even in secret. He has destroyed all defilements. He is worthy of all offerings. Therefore the Buddha is called Arahat.

In this manner one should continue to meditate on the other virtues of the Buddha as well. When we meditate in this manner our minds remain focused directly on the Buddha without straying towards other objects. Thereby our minds become pure and we get solace. We begin to acquire the virtues of the Buddha even though on a small scale. Therefore we should endeavour to practice this meditation.

dhammānupassanā bhāvanā: Dhammānupassanā means reflection on such things as thoughts (cetasika dhamma), aggregates like rūpa, vedanā etc., (khanda), sense-bases like eye and ear, (āyatanadhamma), factors of enlightenment like sati, dhamma vicaya (bojjhangadhamma), and the four noble truths (chaturārya sacca). The meditation could be considered as the most difficult in the satipaṭṭhāna meditation series.

There are five main parts of dhammānupassanā bhāvanā, such as:

- Vivarana pariggaha,

- khandha pariggaha,

- āyatana pariggaha,

- bojjhanga pariggaha, and

- sacca pariggaha.

Nivārana pariggaha: There are five hindrances that obstruct the path to Nibbāna. They are called Nivārana. They are:

- kāmacchanda,

- vyāpāda,

- thīnamiddha,

- uddhacca kukkucca, and

- vicikicchā.

kāmacchanda: means sense desire. This arises as a result of considering objects as satisfactory. One should reflect on kāmacchanda in the following five ways:

- when a sense-desire (kāmacchanda), arises in one’s mind to be aware of its presence;

- when there is no sense-desire in one’s mind to be aware of its absence;

- to be aware of the way in which a sense-desire not hitherto arisen in one’s mind would come into being;

- to be aware of the way in which a sense-desire arisen in one’s mind would cease to be;

- to be aware of the way in which a sense-desire which ceased to exist in one’s mind would not come into existence again.

vyāpāda: This means ill-will. It distorts the mind and blocks the path to Nibbāna. One should reflect on vyāpāda in the following five ways:

- when there arises ill-will (Vyāpāda) in one’s mind, to be aware of its presence;

- when there is no ill-will in one’s mind, to be aware of its absence;

- to be aware of the way in which ill-will not hitherto arisen in one’s mind would come into being;

- to be aware of the way in which ill-will arisen in one’s mind would cease to be;

- to be aware of the way in which ill-will which ceased to exist in one’s mind would not come into existence again.

thīnamiddha: This means sloth in mind and body. This should also be reflected on, in the five ways described earlier as in the case of kāmacchanda and vyāpāda.

uddhacca kukkucca: This means restlessness and worry that arises in the mind. This mental agitation prevents calmness and is a hindrance to the path to Nibbāna. This also should be reflected on, in the five ways already referred to.

vicikicchā: This means skeptical doubt that arises over the following 8 factors regarding the doctrine, namely:

- doubt regarding the Buddha;

- doubt regarding the Dhamma;

- doubt regarding the Sangha;

- doubt regarding the precepts (sikkhā);

- doubt regarding one’s previous birth;

- doubt regarding one’s next birth;

- doubt regarding one’s previous birth and the next birth;

- doubt regarding the doctrine of dependent origination (paticca samuppāda).

This also should be reflected on, in the five ways referred to earlier. The reflection on the fivefold hindrances (nīvarana) taken separately is called nīvarana pariggaha.

khandha pariggaha: A being is composed of five aggregates of clinging. This is the group that grasps life which is based in:

- the aggregate of matter (rūpa upādānakkhandha);

- the aggregate of sensation or feelings (vedanā upādānakkhandha);

- the aggregate of perceptions (saññā upādānakkhandha);

- the aggregate of mental formations (samkhāra upādānakkhandha);

- the aggregate of consciousness (viññāna upādānakkhandha).

One should reflect on matter (rūpa) in the following way:

Matter is of worldly nature. Matter has come into existence in this manner. Matter will cease to be in this manner. The same procedure should be adopted in reflecting on the other aggregates of clinging as well. The aim of this meditation is to get rid of any attachment towards these aggregates and to realize their impermanent nature.

āyatana pariggaha: Āyatana means sense-bases. They are twelve in number and are divided into two parts–external and internal. The six internal sense-bases (adhyātma āyatana) are:

- eye–chakkāyatana,

- ear–sotāyatana,

- nose–ghānāyatana,

- tongue– jivhāyatana,

- body–kāyāyatana, and

- mind–manāyatana.

The six external sense-bases (bāhirāyatana) are:

- form–rūpāyatana,

- sound–saddāyatana,

- smell–gandhāyatana,

- taste–rasāyatana,

- contact–poṭṭhabbāyatana, and

- mental objects–dhammāyatana.

Taking each of these sense-base one should reflect on them in the following five ways:

- knowing what it is,

- knowing how it has come into being,

- knowing how a sense-base not arisen hitherto comes into being,

- knowing how a sense-base that has come into being ceases to be, and

- knowing how a sense-base which has ceased to be does not come into being again.

Once this meditation is practiced with regard to oneself, it could be extended to others as well.

bojjhanga pariggaha: Bojjhanga, or factors of enlightenment, means the conditions that a person striving for enlightenment should follow.

They are seven in number:

- sati sambojjhanga,

- dhamma vicaya sambojjhanga,

- viriya sambojjhanga,

- pīti sambojjhanga,

- passaddhi sambojjhanga,

- samādhi sambojjhanga,

- upekkhā sambojjhanga.

These seven conditions beginning with sati are stages that gradually arise in a person striving for enlightenment and are related to one another. Therefore, it is difficult to describe them separately.

The person who strives for enlightenment acts being mindful of all his thoughts and activities of the body. Such mindfulness is called sati here. With such mindfulness he distinguishes between right and wrong and examines them with wisdom. Such critical examination is called dhammavicaya. This factor of enlightenment connected with wisdom develops in a person striving for enlightenment. The effort of such a person in order to cultivate right (dhamma) having got rid of wrong (adhamma) is here called viriya. The viriya sambojjhanga develops in a person, who strives thus. The happiness that arises in one’s mind by the establishment and the development of right (dhamma) is called pīti sambojjhanga. The calmness that arises in the mind and the body by the development of happiness devoid of sense-desires is called passaddhi. The passaddhi sambojjhanga develops in a person who follows this procedure. Concentrating the mind on a good (kusala) object based on this calmness constitutes the samādhi sambojjhanga. With the development of concentration one realizes the futility of sensations and develops a sense of equanimity (upekkhā) being unaffected by happiness and sorrow. This is called upekkhā sambojjhanga.

In practicing this meditation one should reflect on each of these factors in the following four ways:

- knowing the presence of a factor of enlightenment (bojjhanga) in oneself when it is present;

- knowing the absence of a factor of enlightenment (bojjhanga) when it is absent;

- knowing how a factor of enlightenment could be developed when it is not present in oneself,

- knowing how a factor of enlightenment arisen in oneself could be further developed.

By reflecting in this manner it would be possible to develop the sevenfold factors which assist one to attain Nibbāna.

sacca pariggaha: This means the realization of facts regarding the four noble truths, namely:

- dukkha,

- samudaya,

- nirodha, and

- magga.

dukkha: The truth of suffering: according to the Buddha’s Teaching the entire world, which is in a state of flux, is full of suffering. The Buddha has shown the path to end that suffering. There are twelve ways in which this suffering could be explained.

- Birth is suffering (jāti);

- Old age is suffering (jarā);

- Death is suffering (maraṇa);

- Sorrow is suffering (soka);

- Lamentation is suffering (parideva);

- Physical pain is suffering (dukkha);

- Mental pain is suffering (domanassa);

- Laborious exertion is suffering (upāyāsa);

- Association with unpleasant persons and conditions is suffering (appiyehisampayoga);

- Separation from beloved ones and pleasant conditions is suffering (piyehivippayoga);

- Not getting what one desires is suffering (yampiccam nalabhati tampi dukkaṃ);

- In short, the five aggregates of attachment are suffering (samkhittena pañcupādānakkhandhā dukkhā).

The conception of suffering may also be viewed from seven aspects, as:

- suffering arising from physical pain (dukkha),

- suffering arising from change (viparināmadukkha),

- suffering arising from the coming into being and cessation of conditional states (samkhatadukkha),

- suffering arising from physical and mental ailments but whose cause of arising is concealed (paṭicchannadukkha),

- suffering arising from various trials and tribulations and whose causes of arising are evident (appaṭicchanna dukkha),

- suffering arising from all the types other than dukkha-dukkha (pariyāyadukkha), and

- physical and mental suffering called dukkha-dukkha (nippariyāya dukkha).

Thus one should reflect on suffering in various ways, considering the fact that it is a state conditioned by cause and effect. In this way one should strive to realize the true nature of suffering.

Samudaya: The truth of arising of suffering: by this is meant craving which is the root cause of all suffering.

It is primarily threefold:

- kāma (attachment for worldly objects),

- bhava (attachment for continuity and becoming), and

- vibhava (attachment with the idea that there is no continuity and becoming).

This craving is further classified in relation to the various sense-objects:

- rūpa taṇhā (craving for form),

- sadda taṇhā (craving for sound),

- gandha taṇhā (craving for smell),

- rasa taṇhā (craving for taste),

- poṭṭhabba taṇhā (craving for contact), and

- dhamma taṇhā (craving for mental objects).

Nirodha: Truth of the cessation of suffering: this means the supreme state of Nibbāna resulting from the elimination of all defilements.

It is two-fold, namely:

- attaining Nibbāna and continuing to live (sopadisesa nirvāna), and

- attaining Nibbāna at death (nirupādisesa Nirvāna).

Magga: The noble eight-fold path, which is the only way to attain Nirvāna, is meant by magga which comprises:

- right understanding (sammādiṭṭhi);

- right thought (sammāsankappa);

- right speech (sammāvācā);

- right action (sammākammanta);

- right livelihood (sammā ājīva);

- right effort (sammāvāyāmā);

- right mindfulness (sammāsati);

- right concentration (sammā samādhi).

Each of these factors should be taken separately and reflected on and one should strive to practice them thoughtfully in everyday life.

One should be mindful of one’s thoughts and strive to get rid of evil thoughts and foster right thoughts (sammā saṅkappa) by practicing right understanding (Sammādiṭṭhi). Consequently one should be able to restrain one’s body, speech and mind and through right concentration (sammā samādhi) be able to focus the mind towards the attainment of Nibbāna.

The most significant feature of this four-fold satipaṭṭhāna meditation described so far, is the importance attached therein to the concentration of thoughts without a break from beginning to end. The practice of this meditation diligently will enable one to tread the path to Nibbāna.

According to the visuddhimagga and other important Buddhist texts it is imperative for one who practises this meditation to associate with a learned and noble teacher. This is extremely important because in the absence of such a teacher a person desirous of practicing this meditation could be misled.

By practicing the various sections of the satipaṭṭhāna meditation as part of the daily routine, one would also be able to control and adjust one’s life in a successful manner and thereby lead a household life of peace and contentment.

ahimsāya rato: Takes delight in non-violence, positively takes delight in cultivating loving-kindness. A very special characteristic of the Teaching of the Buddha is the central position given in it to the need to be kind to all beings. Loving-kindness, mettā, the practice of which ensures non-violence, has been extensively dwelt upon by the Buddha.

In his exhortation to Rāhula, the Buddha said: Cultivate, Rāhula, the meditation on loving-kindness; for by cultivating loving-kindness illwill is banished. Cultivate, Rāhula, the meditation on compassion; for by cultivating compassion harm and cruelty are banished.

From this it is clear that mettā and karunā are diametrically opposed to ill-will and cruelty respectively. Ill-will or hate, like sense desire (lust), is also caused by the sense faculties meeting sense objects. When a man’s eye comes in contact with a visible object, which to his way of thinking is unpleasant and undesirable, then repugnance arises if he does not exercise systematic wise attention. It is the same with ear and sound, nose and smell, tongue and taste, body and contact, mind and mental objects. Even agreeable things, both animate and inanimate, which fill man with great pleasure can cause aversion and ill-will. A person, for instance, may woo another whom he loves and entertain thoughts of sensual affection, but if the loved one fails to show the same affection or behaves quite contrary to expectation, conflicts and resentment arise. If he then fails to exercise systematic attention, if he is not prudent, he may behave foolishly, and his behaviour may lead to disaster, even to murder or suicide. Such is the danger of these passions that they will have to be tamed by mettā.

mettā: is a popular term among Buddhists, yet no English word conveys its exact meaning. Friendliness, benevolence, good-will, universal love, loving-kindness are the favourite renderings. Mettā is the wish for the welfare and happiness of all beings, making no restrictions whatsoever. It has the characteristic of a benevolent friend. Its direct enemy is ill-will (hatred) while the indirect or masked enemy is carnal love or selfish affectionate desire (pema, Skt. pema) which is quite different from mettā. Carnal love when disguised as mettā can do much harm to oneself and others. One has to be on one’s guard against this masked enemy. Very often people entertain thoughts of sensual affection, and mistaking it for real mettā think that they are cultivating mettā, and do not know that they are on the wrong track. If one were dispassionately to scrutinize such thoughts one would realize that they are tinged with sensuous attachment. If the feeling of love is the direct result of attachment and clinging, then it really is not mettā.

Carnal love or pema is a kind of longing capable of producing much distress, sorrow and lamentation. This fact is clearly explained by the Buddha in the discourses, and five verses of chapter sixteen on affection in the Dhammapada emphasize it thus:

From what is beloved grief arises,

From what is beloved arises fear.

For him who is free from what he loves

There is no grief and so no fear.From affection, grief arises…

From attachment, grief arises…

From lust grief arises…

From craving grief arises…

As is well known, to love someone means to develop an attachment to the loved one, and when the latter is equally fond of you a bond is created, but when you are separated or when the dear one’s affection towards you wanes, you become miserable and may even behave foolishly. In his formulation of the noble truth of suffering, the Buddha says: Association with the unloved is suffering, separation from the loved is suffering, not to get what one wants is suffering… Mettā, however, is a very pure sublime state of the human, like quicksilver it cannot attach itself to anything. It is a calm, non-assertive super-solvent among virtues.

It is difficult to love a person dispassionately, without any kind of clinging, without any idea of self, me and mine; for in man the notion of ‘I’ is dominant, and to love without making any distinction between this and that, without setting barriers between persons, to regard all as sisters and brothers with a boundless heart, may appear to be almost impossible, but those who try even a little will be rewarded; it is worth while. Through continuous effort and determination one reaches the destination by stages.

A practiser of mettā should be on his guard against callous folk who are egocentric. It often happens that when a person is gentle and sincere others try to exploit his good qualities for their own ends. This should not be encouraged. If one allows the self-centred to make unfair use of one’s mettā, kindliness and tolerance, that tends to intensify rather than allay the evils and sufferings of society.