Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 206-208:

sāhu dassanamariyānaṃ sannivāso sadā sukho |

adassanena bālānaṃ niccam’eva sukhī siyā || 206 ||

bālasaṅgatacārī hi dīghamaddhāna socati |

dukkho bālehi saṃvāso amitteneva sabbadā |

dhīro ca sukhasaṃvāso ñātīnaṃ’va samāgamo || 207 ||

tasmā hi:

dhīrañ ca paññañ ca bahussutaṃ ca dhorayhasīlaṃ vatavantam āriyaṃ |

taṃ tādisaṃ sappurisaṃ sumedhaṃ bhajetha nakkhattapathaṃ’va candimā || 208 ||

206. So fair’s the sight of Noble Ones, ever good their company, by relating not to fools ever happy one may be.

207. Who moves among fools’ company must truly grieve for long, for ill the company of fools as ever that of foes, but weal’s a wise one’s company as meetings of one’s folk.

208. Thus go with the steadfast, wise well-versed, firm of virtue, practice-pure, Ennobled ‘Such’, who’s sound, sincere, as moon in wake of the Milky Way.

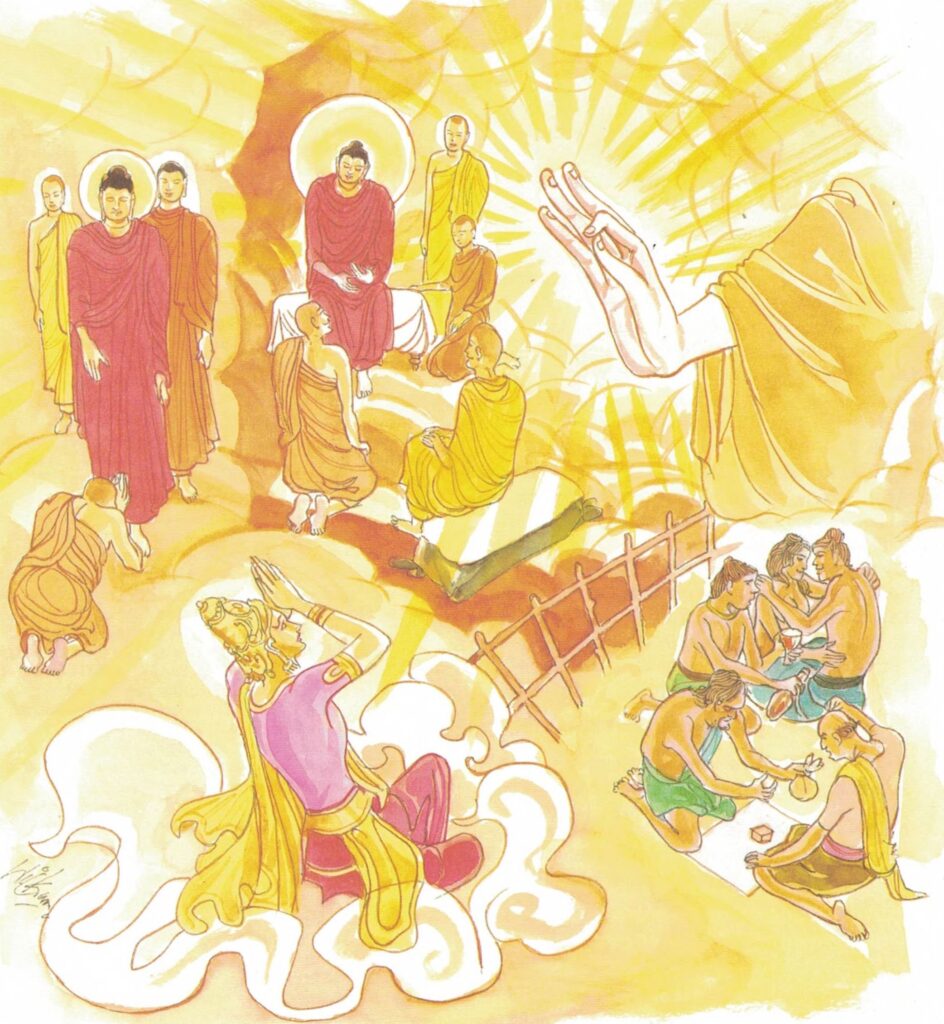

The Story of Sakka

While residing at the village of Veluvana, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to Sakka, the chief of deities.

For when the Buddha’s aggregate of life was at an end and he was suffering from an attack of dysentery, Sakka king of deities became aware of it and thought to himself, “It is my duty to go to the Buddha and to minister to him in his sickness.” Accordingly he laid aside his own body, three-quarters of a league in height, approached the Buddha, saluted him, and with his own hands rubbed the Buddha’s feet. The Buddha said to him, “Who is that?” “It is I, Venerable, Sakka.” “Why did you come here?” “To minister to you in your sickness, Venerable.” “Sakka, to the gods the smell of men, even at a distance of a hundred leagues, is like that of carrion tied to the throat; depart hence, for I have monks who will wait upon me in my sickness.” “Venerable, at a distance of eight-four thousand leagues I smelt the fragrance of your goodness, and therefore came I hither; I alone will minister to you in your sickness.” Sakka permitted no other so much as to touch him and the vessel which contained the excrement of the Buddha’s body; but he himself carried the vessel out on his own head. Moreover, he carried it out without the slightest contraction of the muscles of his mouth, acting as though he were bearing about a vessel filled with perfumes. Thus did Sakka minister to the Buddha. He departed only when the Buddha felt more comfortable.

The monks began a discussion, saying, “Oh, how great must be the affection of Sakka for the Buddha! To think that Sakka should lay aside such heavenly glory as is his, to wait upon the Buddha in his sickness! To think that he should carry out on his head the vessel containing the excrement of the Buddha’s body, as though he were removing a vessel filled with perfumes, without the slightest contraction of the muscles of his mouth!” Hearing their talk, the Buddha said, “What say you, monks? It is not at all strange that Sakka king of gods should cherish warm affection for me. For because of me this Sakka king of gods laid aside the form of old Sakka, obtained the fruit of conversion, and took upon himself the form of young Sakka. For once, when he came to me terrified with the fear of death, preceded by the celestial musician Pañcasikha, and sat down in Indasāla Cave in the midst of the company of the gods, I dispelled his suffering by saying to him, “Vāsava, ask me whatever question you desire in your heart to ask; I will answer whatever question you ask me.” “Having dispelled his suffering, I preached the Dhamma to him. At the conclusion of the discourse fourteen billion of living beings obtained comprehension of the Dhamma, and Sakka himself, even as he sat there, obtained the fruit of conversion and became young Sakka. Thus I have been a mighty helper to him, and it is not at all strange that he should cherish warm affection for me. For, monks, it is a pleasant thing to look upon the noble, and it is likewise a pleasant thing to live with them in the same place; but to have aught to do with simpletons brings suffering.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 206)

ariyānaṃ dassanaṃ sādhu sannivāso sadā sukho

bālānaṃ adassanena niccaṃ eva sukhī siyā

ariyānaṃ [ariyāna]: of noble beings; dassanaṃ [dassana]: sight; sādhu: (is) good;sannivāso [sannivāsa]: associating with them; sadā: (is) always; sukho [sukha]: happy; bālānaṃ [bālāna]: the ignorant; adassanena: not seeing; niccaṃ eva: always; sukhī siyā: is conducive to happiness

Seeing noble ones is good. Living with them is always conducive to happiness. Not seeing the ignorant makes one always happy.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 207)

hi bālasaṅgatacārī dīghaṃ addhānaṃ socati

bālehi saṃvāso amittena iva sabbadā dukkho

dhīro ca ñātīnaṃ samāgamo iva sukha saṃvāso

hi: it is true; bālasaṅgatacārī: he who keeps the intimate company of the ignorant; dīghaṃ addhānaṃ [addhāna]: over a long period of time; socati: regrets (grieves); bālehi saṃvāso [saṃvāsa]: associating with the ignorant; amittena iva sabbadā dukkho [dukkha]: is always as grievous as living with an enemy; dhīro ca: (with) the wise indeed; ñātīnaṃ samāgamo iva: just like the warm company of relations; sukha saṃvāso [saṃvāsa]: is a get-together that is conducive to happiness

A person who keeps company with the ignorant will grieve over a long period of time. Association with the ignorant is like keeping company with enemies–it always leads to grief. Keeping company with the wise is like a reunion with ones’ kinsfolk–it always leads to happiness.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 208)

tasmā hi, dhīraṃ ca paññaṃ ca bahussutaṃ ca dhorayhasīlaṃ vatavantaṃ ariyaṃ

sumedhaṃ tādisaṃ taṃ sappurisaṃ candimā nakkhatta pathaṃ iva bhajetha

tasmā hi: therefore; dhīraṃ ca: wise ones; paññaṃ ca: possessing wisdom; bahussutaṃ ca: well learned; dhorayhasīlaṃ [dhorayhasīla]: practicing the teaching carefully; vatavantaṃ [vatavanta]: adept in following the spiritual routine; ariyaṃ [ariya]: noble; sumedhaṃ [sumedha]: discreet; tādisaṃ [tādisa]: that kind of; taṃ sappurisaṃ [sappurisa]: the virtuous person; candimā iva: just like the moon; nakkhatta pathaṃ [patha]: (associating) the sky–the path of the stars; bhajetha: (you must) associate

The moon keeps to the path of the stars. In exactly the same way, one must seek the company of such noble persons who are nonfluctuating, endowed with deep wisdom, greatly learned, capable of sustained effort, dutiful, noble, and are exalted human beings.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 206-208)

The Buddha’s illness: These three verses refer to the last days of the Buddha. When the Buddha was ill, Sakka came down from heaven to tend and nurse him. The Buddha’s illness, that led to his Great Demise, has been extensively recorded in Buddhist Literature. The Buddha was an extraordinary being. Nevertheless He was mortal, subject to disease and decay as are all beings. He was conscious that He would pass away in His eightieth year. Modest as He was, He decided to breathe His last not in renowned cities like Sāvatthi or Rājagaha, where His activities were centred, but in a distant and insignificant hamlet, like Kusinārā.

Here is a detailed account of the Passing Away of the Buddha.

The Buddha, in the company of the Venerable Ānanda, entered the stream Kakudha, drank its water, and bathed there. After crossing the stream, He entered the mango grove and spoke to the Venerable Cunda. Addressing the Venerable Ānanda, the Buddha said that Cunda should have no remorse that the Buddha fell ill after partaking of the meal offered by him. The Buddha came in the company of monks to the Sāla grove of the Mallas of Kusinārā on the further side of the River Hirannavatī. There the Buddha spoke to the Venerable Ānanda: “Prepare me a bed with its head to the North between the twin Sāla trees. I am tired, and I wish to lie down.”

On the bed prepared there, the Buddha lay down with a steadfast mind on His right side, in the pose of a lion, with one leg resting on the other. Now the twin Sāla trees were in full bloom out of season, and the body of the Buddha was covered with the flowers fallen out of reverence. Divine Mandāra flowers were falling from above. Divine sandal wood powder was dropping from heaven. All these covered the Buddha’s body out of reverence. Divine music filled the atmosphere. The Buddha addressed Ānanda: “O Ānanda, all these flowers, sandal wood powder and divine music are offerings to me in reverence. But no reverence can be made by these alone. If any monk or a nun or a male or female lay disciple were to live according to my teaching and follow my teaching, he pays me the proper respect; he does me the proper honour; and that is the highest offering to me, Therefore, Ānanda, you should act according to my teaching and follow the doctrine, and it should be so taught.”

Now the Venerable Upavāna was standing before the Buddha, and was fanning Him. The Buddha did not like him standing there, and asked him to go to one side. The Venerable Ānanda knew that the Venerable Upavāna was a long-standing attendant of the Buddha, and he could not understand why he was asked to go to one side. So he asked the Buddha why that monk was asked to go to one side. The Buddha explained that at that time all around the Sāla grove of the Mallas up to a distance of twelve leagues, there were heavenly beings standing, leaving no space even for a pin to drop, and that they were grumbling that they could not see the Buddha at His last moment as He was covered by a great monk. The Buddha said how the worldly gods were overgrieved at His passing away, but that the gods who were free from attachment and were mindful had consoled themselves with the thought that all aggregates are impermanent.

The Buddha addressed the Venerable Ānanda again, and said: “There are these four places, Ānanda, which a faithful follower should see with emotion. They are the place of birth of the Buddha, the place where the Buddha attained enlightenment, where the wheel of the doctrine was set in motion, and where the Buddha passed away. Those who may die while on their pilgrimage of these places, will be born in good states after death.” In answer to the Venerable Ānanda, the Buddha said that the funeral rites for the Buddha should be as for a Universal Monarch, and that a Stūpa should be erected at a junction of four roads in honour of the Buddha. The Buddha also said that there are four persons in whose memory a Stūpa should be erected, and that they are the Buddha, a Pacceka Buddha, a disciple of the Buddha and a Universal Monarch.

It was the wish of the Venerable Ānanda that the Buddha should pass away not in a lesser and small town like Kusinārā, but in a great city like Campā. Rājagaha pointed out that Kusinārā had been a great city with a long history, and requested the Venerable Ānanda to inform the Malla princes of Kusinārā of the imminent passing away of the Buddha. Accordingly, the Mallas were so informed at their Town Hall. The Mallas came to the Sāla grove in great grief, and were presented to the Buddha in the first watch of the night.

Just at this time, a wandering ascetic by the name of Subhaddha wanted to see the Buddha to get a certain point clarified, but he was refused admission thrice by the Venerable Ānanda. The Buddha overheard their conversation and entertained him. He wished to know whether the six religious teachers, such as Pūrana Kassapa, were on the correct path. The Buddha said that only those who were on the eightfold noble path shown by Him were on the correct road to emancipation. Subhaddha wished to be a disciple of the Buddha. Accordingly, he was admitted as the last disciple of the Buddha, and he became a sanctified one. In giving further advice to the fraternity of monks, the Buddha said that in the future, the younger monks should not address their elders by their names or clan names or as friends, but as Venerable, or Reverend sir. The elder monks, however, could address the younger monks as friend or by clan name.

The Buddha further said: “If any of you have any doubt or uncertainty whatsoever as to the Buddha, the teaching, the fraternity of monks, the path or the practice, you may seek clarification now. Do not say later that you were facing the Buddha.” Although the Buddha spoke so thrice, no question was asked, and the Venerable Ānanda assured the Master of their answering faith in Him. The Buddha said that even the last of those five hundred monks had attained the path of Sotāpatti, and was certain of emancipation.

Then the Buddha addressed His last words to the monks; “Now, O monks, I exhort you. All component things are subject to decay. Work for your salvation in earnest.”

The Buddha entered into a number of stages of the mind, and after rising from the fourth stage of the trance, passed away. Immediately there arose a frightening and terrifying earthquake, and there burst forth thunders of heaven.

As the Buddha passed away, the Venerable Anuruddha uttered forth: “The exhaling and the inhaling of the passionless Buddha of steadfast mind have ceased, and He has passed away into the final state of bliss. With an open mind He bore up the pain, and the release of His mind was like the extinction of a flame.” The Venerable Ānanda observed: “The passing away of the Buddha is followed by terror with hair standing on ends.” Sahampati Brahma remarked: “Since this Teacher, the supreme individual in the world, endowed with all power and omniscience has passed away, it is natural for all beings in the world to cast away their lives.” Sakka uttered: “All component things are, indeed, impermanent. Everything is in the nature of rise and decay. Whatever that rise is subject to cessation, and blissful is their setting down.” There followed lamentations from worldly monks, but the Venerable Anuruddha exhorted them not to continue their lamentations.

The Venerable Anuruddha and the Venerable Ānanda spent the rest of that night in religious discussion. Then the Venerable Anuruddha suggested that the sad news of the passing away of the Buddha should be conveyed to the Malla princes of Kusinārā. Accordingly, the Venerable Ānanda, accompanied by another monk, went to their assembly at the Town Hall, and conveyed the sad news to them. The Malla princes, as well as the other who heard the news, were overcome with grief, and were in great lamentation.

The Mallās collected all the flowers and perfumes in their kingdom, and with all the music at their disposal went to see the body of the Buddha. For seven days, they paid their highest respects to the body of the Buddha. On the seventh day, eight leaders of the Mallās bathed themselves and being decked in clean garments, tried to raise the body to take it out through the southern gate for cremation. But, they were unable to move the body, and consulted the Venerable Anuruddha on the matter. The Venerable Anuruddha told them that it was the wish of the gods that the body of the Buddha be honoured by the gods as they like and be removed through the northern gate into the middle of the city and be taken out through the eastern gate to be cremated at the Makutabandhana Cetiya of the Mallās. Then the matter was left to the wish of the deities.

Now the entire city of Kusinārā was strewn with divine Mandāra flowers up to knee deep uninterruptedly. After due respect was paid by both gods and the Mallās with flowers, perfumes and music, the body was taken to the Makutabandhana Cetiya of the Mallās. In consultation with the Venerable Ānanda, the Mallās treated the body with all the honour due to a universal monarch. Four leaders of the Mallās, dressed in new garments, tried to set fire to the pyre, but they failed in their attempts. They consulted the Venerable Anuruddha on this point, and were told that until the Venerable Mahā Kassapa came and paid his respects to the body, no one could set fire to the pyre. Now at this time, the Venerable Mahā Kassapa was proceeding from Pava towards Kusinārā, in the company of five hundred monks. On the way, he was resting at the foot of a tree by the side of the road. When he saw an ascetic with a Mandārā flower in his hand coming from the direction of Kusinārā. The Venerable asked him, “Friend, do you know our Teacher?” “Yes, my friend I know Him. He is the Venerable Gotama, who passed away seven days ago. I have taken this Mandārā flower from the place of death.”

When the worldly monks heard this sad news, they began to weep and lament, but the sanctified ones among them consoled themselves by observing that all aggregates are impermanent. One monk by the name of Subhadda, who had entered the order in his old age, expressed his feeling of relief at the passing away of the Buddha as they would no longer be bound by various rules of discipline, etc. The Venerable Kassapa gave an admonition to all the monks there, and proceeded towards Kusinārā.

The Venerable Mahā Kassapa reached the Makutabandhana Cetiya of the Mallās, and went up to the funeral pyre of the Buddha. He adjusted his hands in reverence, went round the pyre three times. Then he uncovered the feet of the Buddha’s body, and worshipped them. The five hundred monks who accompanied him, too, paid their last respects to the Buddha likewise. Immediately, the pyre caught fire by itself, and the body of the Buddha was consumed by the flames. Streams of water from above and from beneath a water tank, and scented water from the Mallās, for one week protected and honoured the remains of the Buddha at the Town Hall.

A portion of the remains of the Buddha was claimed by each of the following, namely, King Ajātasattu of Magadha, Licchavis of Vesāli, Sākyās of Kapilavatthu, Bulis of Allakappa, Koliyas of Rāmagāma, Mallās of Pāvā, and a Brāhmin of Vethadīpa. But the Mallās of Kusinārā maintained that the Buddha passed away within their kingdom, and that they should give no part of the remains to anybody. The Brāhmin Dona settled the dispute by stating that it was not proper to quarrel over the remains of such a sacred personality who taught the world forbearance, and he measured the remains into eight portions, and gave each claimant one measure of the remains. He said for the empty measure, and erected a Stūpa in their respective kingdoms embodying the sacred relics of the Buddha.

sappurisaṃ: the virtuous person. These verses extol the virtues of good people, the ariyas. The qualities and characteristics of virtuous ones are carefully discussed. The following view point establishes the nature of a sappurisa, a good person.

To observe morality is like putting up a fence to protect the house against robbers. The social, economic, political and religious ideals are centred in ethics. The blood of life is love, and morality is its backbone. Without virtue life cannot stand, and without love life is dead. The development of life depends upon the development of virtue and the overflow of love rises when virtue rises.

Since man is not perfect by nature, he has to train himself to be good. Thus morality becomes for everyone the most important aspect in life. Morality is not, for instance, a matter of clothing. The dress that is suitable for one climate, period or civilisation may be considered indecent in another; it is entirely a question of custom, not in any way involving moral considerations, yet the conditions of convention are continually being confused with principles that are valid and unchanging.