Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 9-10:

anikkasāvo kāsāvaṃ yo vatthaṃ paridahessati |

apeto damasaccena na so kāsāvamarahati || 9 ||

yo ca vantakasāvassa sīlesu susamāhito |

upeto damasaccena sa ve kāsāvamarahati || 10 ||

9. One who wears the stainless robe who’s yet not free from stain, without restraint and truthfulness for the stainless robe’s unfit.

10. But one who is self-cleansed of stain, in moral conduct firmly set, having restraint and truthfulness is fit for the stainless robe.

The Story of Devadatta

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery in Sāvatthi, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to Devadatta. For on a certain occasion the two Chief Disciples, each with a retinue of five hundred monks, took leave of the Buddha and went from Jetavana to Rājagaha. The residents of Rājagaha united in twos and threes and in larger groups gave alms in accordance with the custom of giving alms to visitors. Now one day Venerable Sāriputta said, in making the Address of Thanksgiving, “Lay brethren, one man himself gives alms, but does not urge another to give; that man receives in future births the blessing of wealth, but not the blessing of a retinue. Another man urges his neighbour to give, but does not himself give; that man receives in future births the blessing of a retinue, but not the blessing of wealth. Another man neither himself gives alms nor urges others to give; in future births that man receives not so much as a bellyful of sour rice-gruel, but is forlorn and destitute. Yet another both himself gives alms and urges his neighbour to give; that man, in future births in a hundred states of existence, in a thousand states of existence, in a hundred thousand states of existence, receives both the blessing of wealth and the blessing of a retinue.” Thus did Venerable Sāriputta preach the law.

One person invited the Venerable to take a meal with him, saying, “Venerable, accept my hospitality for tomorrow.” For the alms-giving someone handed over a piece of cloth, worth one hundred thousand, to the organizers of the alms giving ceremony. He instructed them to dispose of it and use the proceeds for the ceremony should there be any shortage of funds, or if there were no such shortage, to offer it to anyone of the monks they thought fit. It so happened that there was no shortage of anything and the cloth was to be offered to one of the monks. Since the two Chief Disciples visited Rājagaha only occasionally, the cloth was offered to Devadatta, who was a permanent resident of Rājagaha.

It came about this way. Some said, “Let us give it to the Venerable Sāriputta.” Others said, “The Venerable Sāriputta has a way of coming and going. But Devadatta is our constant companion, both on festival days and on ordinary days, and is ever ready like a water-pot. Let us give it to him.” After a long discussion it was decided by a majority of four to give the robe to Devadatta. So they gave the robe to Devadatta. Devadatta cut it in two, fashioned it, dyed it, put one part on as an undergarment and the other as an upper garment, and wore it as he walked about. When they saw him wearing his new robe, they said, “This robe does not befit Devadatta, but does befit the Venerable Sāriputta. Devadatta is going about wearing under and upper garments which do not befit him.” Said the Buddha, “Monks, this is not the first time Devadatta has worn robes unbecoming to him; in a previous state of existence also he wore robes which did not befit him.” So saying, he related the following.

Once upon a time, when Brahmadatta ruled at Benāres, there dwelt at Benāres a certain elephant-hunter who made a living by killing elephants. Now in a certain forest several thousand elephants found pasture. One day, when they went to the forest, they saw some Private Buddhas. From that day, both going and coming, they fell down on their knees before the Private Buddha before proceeding on their way.

One day the elephant-hunter saw their actions. Thought he, “I too ought to get a yellow robe immediately.” So he went to a pool used by a certain Private Buddha, and while the latter was bathing and his robes lay on the bank, stole his robes. Then he went and sat down on the path by which the elephants came and went, with a spear in his hand and the robe drawn over his head. The elephants saw him, and taking him for a Private Buddha, paid obeisance to him, and then went their way. The elephant which came last of all he killed with a thrust of his spear. And taking the tusks and other parts which were of value and burying the rest of the dead animal in the ground, he departed.

Later on the Future Buddha, who had been reborn as an elephant, became the leader of the elephants and the lord of the herd. At that time also the elephant-hunter was pursuing the same tactics as before. The Buddha observed the decline of his retinue and asked, “Where do these elephants go that this herd has become so small?” “That we do not know, master.” The Buddha thought to himself, “Wherever they go, they must not go without my permission.” Then the suspicion entered his mind, “The fellow who sits in a certain place with a yellow robe drawn over his head must be causing the trouble; he will bear watching.”

So the leader of the herd sent the other elephants on ahead and walking very slowly, brought up the rear himself. When the rest of the elephants had paid obeisance and passed on, the elephant-hunter saw the Buddha approach, whereupon he gathered his robe together and threw his spear. The Buddha fixed his attention as he approached, and stepped backwards to avoid the spear. “This is the man who killed my elephants,” thought the Buddha, and forthwith sprang forwards to seize him. But the elephant-hunter jumped behind a tree and crouched down. Thought the Buddha, “I will encircle both the hunter and the tree with my trunk, seize the hunter, and dash him to the ground.” Just at that moment the hunter removed the yellow robe and allowed the elephant to see it. When the Great Being saw it, he thought to himself, “If I offend against this man, the reverence which thousands of Buddhas, Private Buddhas, and Arahats feel towards me will of necessity be lost.” Therefore he kept his patience. Then he asked the hunter, “Was it you that killed all these kinsmen of mine?” “Yes, master,” replied the hunter. “Why did you do so wicked a deed? You have put on robes which become those who are free from the passions, but which are unbecoming to you. In doing such a deed as this, you have committed a grievous sin.” So saying, he rebuked him again for the last time. “Unbecoming is the deed you have done,” said he.

When the Buddha had ended this lesson, he identified the characters in the Jātaka as follows, “At that time the elephanthunter was Devadatta, and the noble elephant who rebuked him was I myself. Monks, this is not the first time Devadatta has worn a robe which was unbecoming to him.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 9)

anikkasāvo damasaccena apeto yo kāsāvaṃ

vatthaṃ paridahessati so kāsāvaṃ na arahati

anikkasāvo [anikkasāva]: uncleaned of the stain of defilements; damasaccena: emotional control and awareness of reality; apeto [apeta]: devoid of; Yo: some individual; kāsāvaṃ vatthaṃ [vattha]: the stained cloth; paridahessati: wears; so: that person; kāsāvaṃ [kāsāva]: the stained robe; na arahati: is not worthy of.

A monk may be stained with defilements, bereft of self-control and awareness of reality. Such a monk, though he may wear the ‘stained cloth’ (the monk’s robe which has been specially coloured with dye obtained from wild plants), he is not worthy of such a saintly garb.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 10)

yo ca vantakasāvassa sīlesu susamāhito

damasaccena so upeto sa ve kāsāvaṃ arahati

Yo ca: if some person; vantakasāvassa: free of the stain of defilements; sīlesu: well conducted; susamāhito [susamāhita]: who is tranquil within; damasaccena: with emotional control and awareness of reality; upeto [upeta]: endowed; so: that person; ve: certainly; kāsāvaṃ [kāsāva]: the stained cloth; arahati: is worthy of.

Whoever dons the ‘stained cloth’, being free of defilements, who is well conducted and tranquil within, having emotions under control and aware of reality, such a person is worthy of the sacred ‘stained cloth.’

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 9-10)

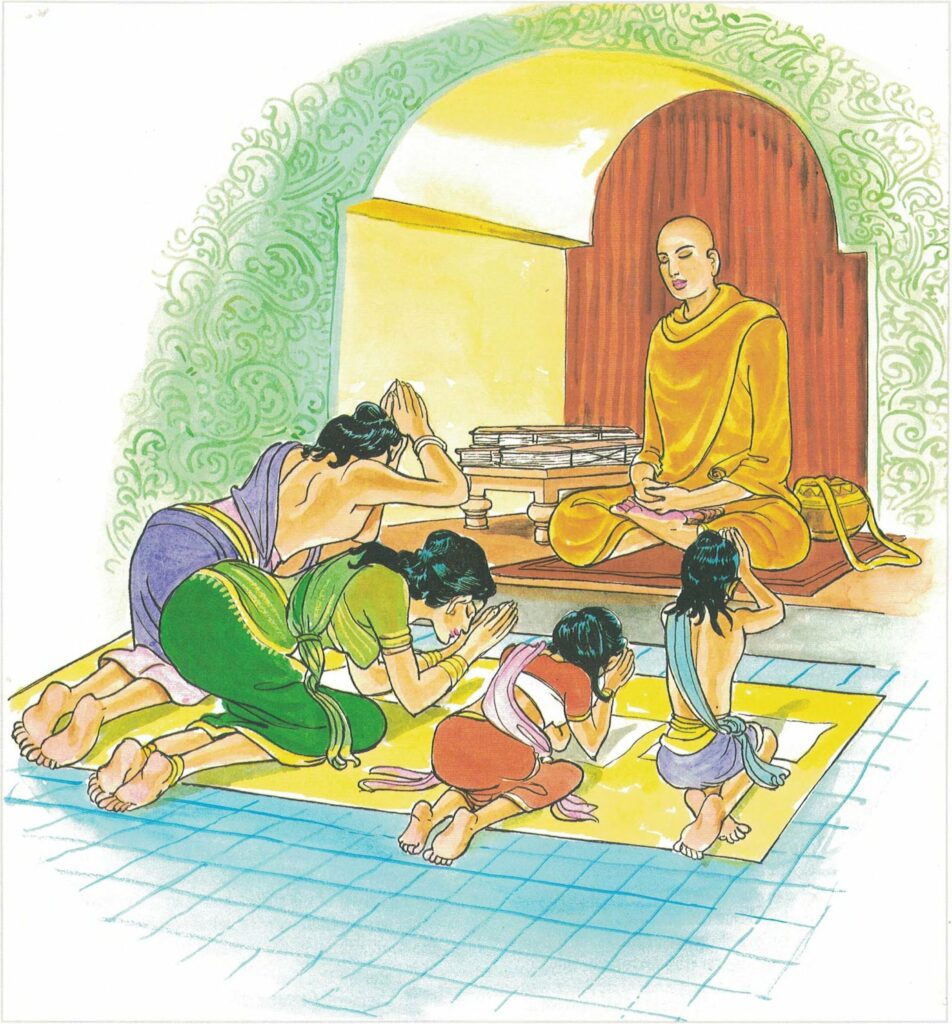

The ‘stained cloth’ is a symbol of purity for the Buddhist. He holds as sacred and holy this specially prepared monk’s robe. The Buddhist bows down in homage to the wearer of this robe. The robe signifies the Sangha which is a part of the Holy Trinity of the Buddhist: Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha.

When a person is ordained as a Buddhist monk, the person feels that he has risen above the mundane realm and become a holy person. This feeling is reinforced when laymen bow down before him. This new ‘self-image’ helps the newly ordained person to start a new life of holiness. The layman too gets inspiration by seeing and worshiping the wearer of the robe. This veneration of the robe, therefore, is an important part of the Buddhist practice.

This is why a person contaminated by profanity is not worthy of the yellow cloth. It is a sacrilege to wear it, if he is impure. It is a desecration of the sacred robe.