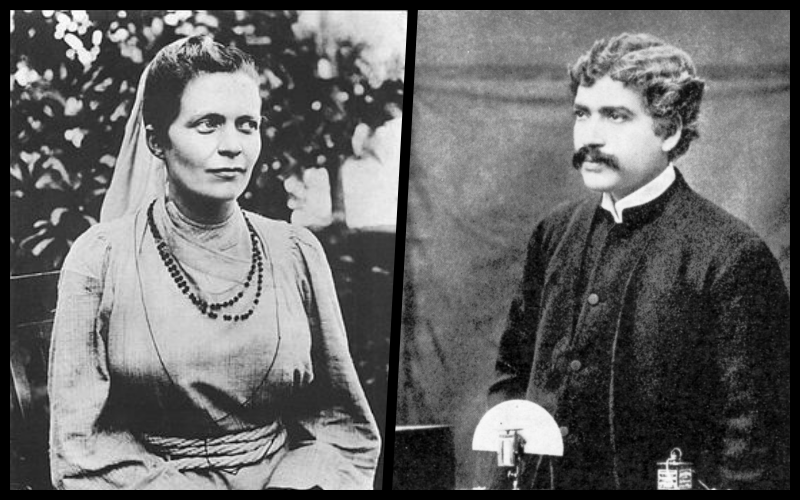

The Scientist and the Nun

Margaret Elizabeth Noble, later Sister Nivedita, was born on 28th October 1867 in North Ireland in a Scottish Irish family. Losing her father at the age of ten, she studied in a charity institution – Halifax School and Orphan Home, and after completing her school, took up a teaching job – a vocation getting common among the women in Britain then. She was an innovative teacher influenced by the New Education Movement that was sweeping the West then, the patron-saints of which were the Swiss educationist Pestalozzi and his German disciple Froebel who developed the concept of the kindergarten. Nivedita’s life changed after she met Vivekananda in 1895 in England. Inspired to walk in his footsteps, Margaret arrived in India in January 1898 and was given the name ‘Nivedita’ by Vivekananda.

While Nivedita is remembered variously today, this piece highlights her contribution towards supporting perhaps the greatest pioneering Indian scientist, Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose. She not only acted as his chief motivator, but also for years organised financial support for all his work. Bose, even when he had built considerable reputation in late 1890s as one of the pioneers in radio transmission, was given a highly discriminatory treatment – getting a small fraction of the salary of what his English colleagues in at Presidency College Calcutta received (in protest, he declined to accept any remuneration for his work until it was corrected), getting blocked out of paper publications in journals, and almost a total absence of facilities for conducting research. His subsequent work was pushing the boundaries between ‘living’ and ‘non-living’, between – in his own words – physics and physiology.

Nivedita was quick to assess the man’s genius and knew he was best-suited to raise the national prestige at a time when it was said that no Indian university had produced even a single original mind since the beginning of the universities in the Presidency towns in 1858. Both Vivekananda and Nivedita were with Bose in Paris in 1899 when the latter made considerable impression in the international scientific fraternity by his findings. The Bose couple then stayed at Nivedita’s home in Wimbledon in 1900 where her mother Mary Noble hosted them. Bose, then severely ill, spent a month in recuperation in care of Nivedita’s family.

It was when he was in England that Bose realised that he was up against a whole establishment bent upon crushing his advancement and spirit. In a letter written in 1902 from London to his fellow-Brahmo Rabindranath Tagore describes his state of mind :

“You will not know what difficulties I have to face. You cannot imagine. The publication of my article on ‘Plant Response’, which I wrote in last May in the Royal Society, was stopped by the conspiracy of Waller and Sanderson. But my discoveries have been published by Waller in his own name in a journal last November. All these days I did not know about it.…..I am depressed. I wish to return now and regain the spirit of life by touching the dust of Bharata.”

Ever since then till her death (at the age of 43) in 1911, Nivedita organised the required resources for Bose towards his research and laboratory, chiefly through the gifts from Sara Chapman Bull (widow of the Norwegian violin maestro Ole Bull, a devoted disciple of Vivekananda, whom the latter addressed as Mother or ‘Dhiramata’. Though she was nine years younger to Bose, Nivedita almost had a maternal feeling of protecting him. Indeed she often referred to him as ‘Bairn’ (child).

Nivedita was also fascinated by the theme of his work – which she saw was in line with the Vedantic idea of ‘oneness of the entire existence’. When she realised the extent of discrimination Bose faced in publishing his research in the Western academic journals, she encouraged him to directly take his work to the world by way of books, something Bose too had thought of, but an enterprise he was too depressed to take up then. Recharging his vigour and faith, Nivedita actively helped him write four of his books—Living and Non-Living, Plant Response, Comparative Electro-Physiology, and Irritability of Plants, editing them – indeed the language eminently bears Nivedita’s mark, while not taking any credit for her efforts. She also revised his papers published in the journal ‘Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society’. She continuously wrote about him in newspapers and journals to attract wider attention to his extraordinary talent, tenacity and achievement. Bose was a daily visitor to ‘House of the Sisters’ -17 Bosepara Lane, in the humble neighbourhood of Bagh Bazaar in North Calcutta, where Nivedita along with Sister Christine (a German-American disciple of Vivekananda) stayed. Through most part of 1904 and 1905 they worked together almost every day on the books. Bose’s wife, Lady Abala, as well his sister Labanyaprabha volunteered to teach in Nivedita’s Girls’ School conducted then in the house itself. It was Nivedita’s dream that India should have its own high-class research institute and very much wanted Bose to set up one. She had even arranged continuous stream of funding for Bose’s work in the event of her death. An emotional Bose during the inauguration of the Bose Institute (Basu Vigyan Mandir) in 1917 (6 years after Nivedita’s death) said, “In all my struggling efforts, I have not been altogether solitary. While the world doubted, there have been a few, now in the city of silence, who never wavered in their trust.” In one of his letters he wrote, “Sister Nivedita was also greatly interested in the revival of all intellectual advances made by India, and it was her strong belief in the advance of Modern Science accomplished by Indian Men of Science that led me to found my Research Institute.” In a letter to Nivedita’s younger sister Mrs Wilson, he said, “She had not body, it was all mind.”

At the Bose Institute is placed the bas-relief of a woman with prayer-beads and a lamp in her hand, designed by the Maharshtrian sculptor, Vinayak Pandurang Karmakar, modeled on the famous painting of Nivedita by Nandalal Bose (himself in many ways a protégé of Nivedita) – ‘The lady with the lamp’. A portion of Nivedita’s ashes is also kept there. Its emblem is the ‘Vajra’, which Nivedita designed and proposed for a possible National Emblem and Flag as early as 1906.

No less a person than Tagore, who had the privilege of knowing both Bose and Nivedita well, said after the passing away of Bose in 1937 : ‘In the days of his struggles, Jagadish gained an invaluable energizer and helper in Sister Nivedita and in any record of his life’s work, her name must be given a place of honour.’

The Bose couple used to take Nivedita during the Puja holidays to Darjeeling and sometimes to Mayavati in Uttarakhand where they stayed at the Advaita Ashram of the Ramakrishna Mission. As fate would have it, it was in the company of the Boses that Nivedita spent her last days and breathed her last in Darjeeling. During the Puja break of 1911, they had gone to Darjeeling where the Boses had rented a cottage – Roy Villa – for their stay. As early as 1904, Nivedita had said that she will probably die in 1912. Now broken in health due to years of strain and hard living, she had a severe attack of blood dysentery, and spent her last few days waiting for final departure. During the last night she said to the Boses ‘the boat is sinking but I shall yet see the sun rise’. It was just after dawn when she uttered the famous verse from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad – ‘Asato Ma Sadgamay, Tamaso Ma Jyotirgamay, Mrityorma Amritam Gamay’ – and passed into Eternal Sleep. Lady Abala Bose later said, ‘How manifold were the blessings she conferred on all who came in contact with her, and in how many directions she had effectively served our Motherland, it is too early yet to speak.’

Nivedita was cremated in Darjeeling and her last funeral procession was one seldom witnessed before in the hill-station. An inscription at her cremation-spot says : ‘Here Reposes Sister Nivedita Who Gave Her All To India’. Few have ever deserved the description more befittingly.