Early Life

One day at Dakshineswar Sri Ramakrishna in a state of ecstasy sat on the lap of a young man and said afterwards, ‘I was testing how much weight he could bear.’ The young man was none other than Sharat Chandra, and the burden he had to bear in later life as the Secretary of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission required superhuman strength. He succeeded because with implicit faith in the Master he could maintain his equanimity under trying circumstances and could tell all around him, ‘The Master will set everything right. Be at rest.’

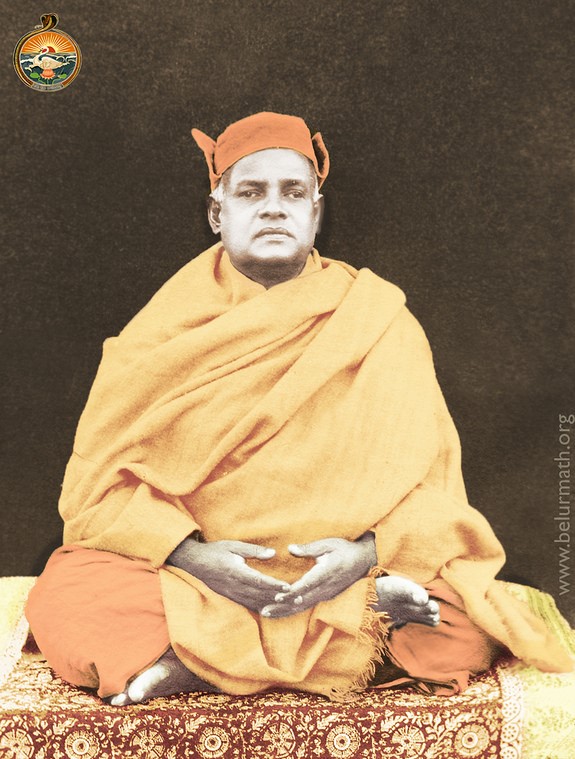

Swami Saradananda came of a rich and orthodox brahmin family, living in Amherst Street, Calcutta. His early name was Sharat Chandra Chakravarti. He was born on 23 December 1865. As the time of birth was a Saturday evening, many were alarmed as to the future of the child. But an uncle of Sharat Chandra, an expert in astrology, predicted that the newborn baby would be so great that he would shed lustre on his family.

From his very boyhood Sharat Chandra was so quiet that this could be mistaken for dullness. But soon he showed his extraordinary intelligence in school. In almost all examinations he topped the list of successful boys. He took delight in many extra-academic activities, and became a prominent figure in the debating class, and his strong physique developed through physical exercise, attracted notice.

His deep religious nature expressed itself even in his early boyhood. He would sit quietly by the side of his mother when she was engaged in worshipping the family deity, and afterwards faultlessly repeat the ritual before his friends. On festive occasions he would want images of deities and not the dolls which average children buy, and for a long time the play which interested him most was to perform imitation-worship. After he was invested with the sacred thread, he was privileged to perform regular worship in the family shrine. He was also strict about the daily meditations required of a brahmin boy.

Sharat was very courteous by nature. He was incapable of using any harsh word to anybody or of hurting anyone’s feelings in any way. He had a very soft and feeling heart, and lost no opportunity to help his poor class friends as far as his means permitted. The small sum of money which he got from home for tiffin, he often spent for poor boys. Sometimes he would give away his personal clothing to those who needed them more. Relatives and friends, acquaintances and neighbours, servants and housemaids—whoever fell ill, Sharat Chandra was sure to be by their side. Once a maidservant in a neighbouring house fell ill of cholera. Her employer removed her to a corner on the roof of his house to prevent infection, and left her there to die. But as soon as Sharat Chandra came to know of this, he rushed to the spot and all alone did everything that was necessary for her nursing. The poor woman died in spite of all his devoted service. Finding the employer indifferent about her last rites, Sharat made arrangements even for that.

As he grew up, he came under the influence of the great Brahmo leader Keshab Chandra Sen. Gradually, he began to study the literature of the Brahmo Samaj and even to practise meditation according to its system.

In 1882 Sharat Chandra passed the University Entrance Examination from the Hare School and the next year he got himself admitted into the St. Xavier’s College. Father Laffont was then the Principal of that college. Being charmed with the deep religious nature of Sharat, he undertook to teach him the Bible.

Sharat had a cousin, Shashi, who also stayed in the same family and studied at the Metropolitan College. Once a class friend of Shashi said that there was a great saint in the templegarden of Dakshineswar about whom Keshab Chandra had written in glowing terms in the Indian Mirror. In the course of conversation the three decided that one day they would visit the saint.

With Sri Ramakrishna

It was on a certain day in October 1883, that Sharat and Shashi were at Dakshineswar. Sri Ramakrishna received them very cordially. After preliminary inquiries, when the Master learnt that they now and then went to Keshab’s Brahmo Samaj, he was very pleased. Then he said, ‘Bricks and tiles, if burnt after the trademark has been stamped on them, retain these marks for ever. But nowadays parents marry their boys too young. By the time they finish their education, they are already fathers of children and have to run hither and thither in search of a job to maintain the family.’ ‘Then, sir, is it wrong to marry? Is it against the will of God?’ asked one from the audience. The Master asked him to take down one of the books from the shelf and read aloud an extract from the Bible setting forth Christ’s opinion on marriage: ‘For there are some eunuchs, which were so born from their mother’s womb; there are some eunuchs which were made eunuchs of men, and there be eunuchs which have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven’s sake. He that is able to receive let him receive.’ And St. Paul’s: ‘Say therefore to the unmarried and widows, it is good for them if they abide even as I. But if they cannot contain, let them marry: for it is better to marry than to burn.’ When the passage was read, the Master remarked that marriage was the root of all bondage. One among the audience interrupted him saying, ‘Do you mean to say, sir, that marriage is against the will of God? And how can His creation go on if people cease to marry?’ The Master smiled and said, ‘Don’t worry about that. Those who like to marry are at perfect liberty to do so. What I said just now was between ourselves. I say what I have got to say, you may take as much or as little of it as you like.’

These stirring words of renunciation opened up a new vision to Sharat and Shashi. Both were charmed by the personality of Sri Ramakrishna. The college where Sharat was studying remained closed on Thursdays. He made it a rule to visit Dakshineswar every Thursday unless something very important stood in the way. As he came more and more in touch with Sri Ramakrishna, he was more and more attracted towards him. Sharat Chandra was caught in the current of his love.

The Master also noticed the spiritual potentiality of the boy at the very first sight and began to give directions and to watch his spiritual development. One day the Master was seated in his room at Dakshineswar surrounded by a group of devotees. Ganesha, the Hindu god of success, was the topic of conversation. The Master praised highly the integrity of character of this deity, his utter absence of passion and single-minded devotion to his mother, the goddess Durga. Young Sharat was present. Suddenly he said, ‘Well, sir, I like the character of Ganesha very much. He is my ideal.’ The Master at once corrected him saying, ‘No, Ganesha is not your ideal. Your ideal is Shiva. You possess Shiva attributes.’ Then he added, ‘Always think of yourself as Shiva and of me as Shakti. I am the ultimate repository of all your powers.’

On another occasion the Master asked Sharat, ‘How would you like to realise God? What divine visions do you prefer to see in meditation?’ Sharat replied, ‘I do not want to see any particular form of God in meditation. I want to see Him as manifested in all creatures of the world. I do not like visions.’ The Master said with a smile, ‘That is the last word in spiritual attainment. You cannot have it all at once.’ ‘But I won’t be satisfied with anything short of that,’ replied the boy, ‘I shall trudge on in the path of religious practice till that blessed state arrives.’

Sharat Chandra had once met Narendranath—afterwards Swami Vivekananda—even before he came to Sri Ramakrishna. But at that time Sharat had formed a very wrong impression about one whom afterwards he loved and followed as a leader. Sharat had once gone to see a friend in central Calcutta about whom the report was that he had gone astray. At the house of the friend he met a young man who talked of high things but who seemed to be self-conceited and whose manners were anything but decorous. Sharat came to the conclusion that it was by mixing with this young man that his friend had gone wrong.

A few months after this, Sri Ramakrishna was greatly praising a young man named Narendranath. He was speaking so highly of him that Sharat Chandra felt tempted to have a personal acquaintance with such a person, and got his address from Sri Ramakrishna for this purpose. And what was his wonder when on meeting Narendranath, he found that he was none other than the young man whom once he had met at the house of his friend! The first acquaintance soon ripened into close friendship. So great was their attachment to each other that sometimes Sharat and Narendra could be found in the streets of Calcutta, deeply engaged in conversation, till one o’clock in the morning—walking the distance between their homes many times—one intending to escort the other to the latter’s home. Sharat Chandra afterwards used to say, ‘However freely Swamiji (Swami Vivekananda) mixed with us, at the very first meeting I saw that here was one who belonged to a class by himself.’

One interesting incident happened when Narendra once went inside the house of Sharat Chandra. It was the winter of 1884. Sharat and Shashi came to the house of Narendranath at noon. Conversation warmed up, and all forgot how time passed. So long Sharat and Shashi had thought that Sri Ramakrishna was only a saint. Now on hearing what Narendra had experienced with Sri Ramakrishna they began to think he was as great as Jesus or any other prophet of similar rank. In the course of the conversation the day passed into evening. Narendranath took them to Cornwallis Square for an evening stroll. There also the conversation continued, broken by a song sung by him. Suddenly, Sharat woke up to the consciousness of time as he heard a clock strike nine at night. Narendra proceeded with them to give them his company for a little distance. But engaged in talk he came actually to the house of Sharat Chandra, and Sharat requested him to take his meals there. Narendra agreed. But as he entered the house, he stopped in astonishment. It seemed as if he had been in this house before, and knew every corridor, every room there! He wondered if it could be the memory of any past life.

The Master was glad beyond measure when he learnt that Sharat Chandra had not only met Narendranath, but that a deep love had sprung up between the two. He remarked in his characteristic, homely way, ‘The mistress of the house knows which cover will go with which cooking utensil.’

Sharat passed the First Arts Examination in 1885. His father wanted him to study medicine, specially as he had a pharmacy for which he had to employ a doctor. Though Sharat had no aspiration to be a doctor, on the advice of Narendranath he joined the Calcutta Medical College. But destiny willed that Sharat was not to be a medical man. When the Master fell ill, and he was removed to Cossipore, Sharat, along with others, began to serve him there.

Sharat Chandra’s father was alarmed at this development. He had, as his family guru, Jaganmohan Tarkalankar, a famous pundit and an adept in various kinds of Tantrika practices.

Leaving aside such a capable preceptor, should Sharat follow another person! Girish Chandra, Sharat’s father, one day took Jaganmohan Tarkalankar to Sri Ramakrishna at Cossipore. His idea was that in the course of conversation between the family preceptor and Ramakrishna it would transpire what a pigmy the latter was in comparison with the former, and Sharat would clearly see his folly in giving up the family guru. But in a moment’s talk, an adept like the pundit found that he was in the presence of a blazing fire. Secretly he told Girish that his son should be considered blessed to have such a guru.

So Sharat continued to serve the Master. His steadfastness in this work was put to test on the first of January 1886, when the Master in an ecstatic mood blessed many a devotee with a touch which lifted their minds to great spiritual heights. Finding the Master in such a mood of compassion, all who were nearby rushed to the spot to receive his blessings. But Sharat and Latu at that time were engaged in some duty allotted to them. Even the consideration of a spiritual windfall could not tempt them away. Afterwards, when asked as to why he did not go to the Master at that time, Sharat replied, ‘I did not feel any necessity for that. Why should I? Was not the Master dearer than the dearest to me? Then what doubt was there that he would give me, of his own accord, anything that I needed? So I did not feel the least anxiety.’

One day the Master commanded the young disciples to go out and beg their food. They readily obeyed. But with their nice appearance they could hardly hide the fact that they belonged to good families. So when they went out for alms, some were pitied, some were abused, some were treated with utmost sympathy. Sharat Chandra would afterwards narrate his own experience with a smile thus: ‘I entered a small village and stood before a house uttering the name of God just as the begging monks do.

Hearing my call an elderly lady came out and when she saw my strong physique, at once she cried out in great contempt, “With such a robust health are you not ashamed to live on alms? Why don’t you become a tram conductor at least?” Saying this, she closed the door with a bang.’

Baranagore Days

When, after the passing away of the Master, Sharat returned home, his parents were at rest. But Narendranath and others would come to his house now and then and the subject of conversation would be only how to build up their lives in the light of the message of the Master. At their call Sharat would visit the monastery now and then. This alarmed his father, who reasoned with Sharat, ‘So long as Sri Ramakrishna was alive, it was all right that you lived with him—nursing and attending on him. But now that he is no more, why not settle down at home?’ But seeing that arguments had no effect, he locked his son within a room, so that he might not go and mix with the other young disciples of the Master. Sharat was not perturbed in the least. He began to spend his time in meditation and other spiritual practices. But as chance would have it, a younger brother opened the door of the room out of sympathy for his elder brother, who then came out and fled to the monastery at Baranagore.

During the Christmas holidays of 1886, Narendra and others went to Antpur, the birthplace of Swami Premananda, and there they resolved to lead a life of renunciation. Soon after they formally took sannyasa, and Sharat became known as Swami Saradananda. His parents came to know of this and visited Baranagore, this time not to dissuade but to give him the complete liberty to follow the line of action he had chosen.

Now began a life of real tapasya. At Baranagore, at the dead of night, Narendranath and Sharat Chandra would secretly go out to the place where the body of the Master was cremated, or to some such spot, and practise meditation. Sometimes they would spend the whole night in spiritual practices. Though so much inclined towards the meditative life, Sharat Chandra was ever ready to respond to the call of work. And with his innate spirit of service he was sure to be found near the sick-bed if any of the brother disciples fell ill.

Swami Saradananda or Sharat Maharaj, as he was known in the Order, had a sweet musical voice which from a distance could be mistaken for that of a woman. One night some neighbours, led by curiosity as to how a woman could be there at the monastery, scaled the boundary wall and entered the place of music. They were ashamed of themselves after discovering the truth and frankly apologized. When Saradananda read the Chandi or recited hymns with his melodious voice, the bystanders felt spiritually uplifted. Afterwards, even in advanced age, he would sing one or two songs, out of overflowing love and devotion, on the occasion of the birthday of Sri Ramakrishna or Swami Vivekananda.

Austerity and Pilgrimages

Soon Swami Saradananda began to feel a longing for a life of complete reliance on God. So he went to Puri to practise tapasya. After returning to Baranagore he started for Varanasi and Ayodhya and at last reached Rishikesh via Hardwar. Here he passed some months in tapasya, till in the summer of 1890 he started for Kedarnath and Badrinarayan via Gangotri with Swami Turiyananda and Vaikuntha Nath Sannyal. This pilgrimage was full of thrilling experiences for them. Some days they had to go without food, some days without shelter. Even on such a difficult journey he was not slow in doing acts of utmost sacrifice. Once on the way they were climbing down a very steep hill with the help of others. The two gurubhais were ahead, Swami Saradananda was behind. As Swami Saradananda was climbing down slowly, he found a party behind in which there was an old woman. She found it hard to descend as she was without a stick. Swami Saradananda quietly handed his stick to the old lady—following the historic example, ‘Thy need is greater than mine.’

After visiting Kedarnath, Tunganath, and Badrinarayan, Swami Saradananda and Vaikuntha Nath came to Almora on 12 August 1890, and became the guests of Lala Badrinath Shah. Swamiji (Swami Vivekananda) and Swami Akhandananda also reached Almora, and all of them started for Garhwal. After seeing various places in Garhwal, as they arrived at Tehri, Swami Akhandananda fell ill. As there was no good doctor in the town, he was taken to Dehradun. On their way, at Rajpur, below Mussoorie, they met Swami Turiyananda unexpectedly. Swami Turiyananda had separated from Swami Saradananda on the way to Kedarnath and had come here for tapasya. When Swami Akhandananda was slightly better, he went to Meerut, and Swamiji, Turiyananda, and Saradananda went to Rishikesh, where they heard that Swami Brahmananda was practising tapasya at Kankhal near Hardwar. So they all went to meet him at Kankhal, where they learnt that Swami Akhandananda was at Meerut. Hence the whole party went to Meerut to have the pleasure of seeing him. At Meerut they all lived together for a few months before they came to Delhi. At Delhi Swamiji left them to wander alone. Then Swami Saradananda came to Varanasi visiting holy places like Mathura, Vrindavan, Allahabad, on the way. At Varanasi Swami Saradananda stayed for some time practising intense meditation. Here an earnest devotee, in search of a guru, met him and was so much impressed by him that he afterwards took sannyasa from him. He then became Swami Satchidananda. In the summer of 1891, Swami Abhedananda met Swami Saradananda at Varanasi, and the two, accompanied by Swami Satchidananda made a ceremonial circuit on foot, round the sacred area of the city covering about forty square miles. This caused them so much hardship that all the three were attacked by severe fever. Some time after they had recovered from fever Swami Saradananda got dysentery, which compelled him to return to the monastery at Baranagore in September, 1891.

At Baranagore with better facilities for medical care, Swami Saradananda completely recovered. Then he started for the Holy Mother’s native village, Jayrambati, to see her. Although he had a very happy time here, he got malaria and suffered for a long time even after returning to Baranagore.

In Europe and America

When Swamiji’s work in the West made headway, he was in need of an assistant, and the choice finally fell upon Swami Saradananda. So when Swami Vivekananda came to London for the second time in 1896, he met Swami Saradananda who had arrived there on 1 April. Swami Saradananda delivered a few lectures in London, but he was soon sent to New York, where the Vedanta Society had already been established. Soon after his arrival in America he was invited to be one of the teachers at the Greenacre Conference of Comparative Religions. At the close of the Conference, the Swami was invited to lecture in Brooklyn, New York, and Boston. Everywhere his dignity of bearing, gentle courtesy, the readiness to meet questions of all kinds, and above all, the spiritual height from which he could talk, won for him a large number of friends, admirers, and devotees. Swami Saradananda afterwards settled down in New York to carry on the Vedanta movement in a regular and organized way.

Holy Mother in Udbodhan

When Swami Trigunatitananda left for America to take up the work of Swami Turiyananda, the Bengali magazine Udbodhan faced a crisis financially and otherwise. Swami Saradananda now played a decisive part in keeping it alive. A few years later he thought that the Udbodhan should have a house of its own. There was a need also for a house for the Holy Mother to stay in when she came to Calcutta. So the Swami planned to have a building where downstairs there would be the Udbodhan office, and upstairs would be the shrine and the residence of the Holy Mother. Especially the second reason so much weighed with the Swami, that he started the work by borrowing money on his personal responsibility in spite of strong opposition from many quarters.

This was a blessing in disguise. For to repay the loan Swami Saradananda had to write Sri Ramakrishna Lilaprasanga— discourses on the life of the Master—which has become a classic in Bengali literature. Yet for this great achievement the Swami would not accept the least credit. He would say that the Master had made him the instrument to write this book. The book, in five parts, is still incomplete. When hard pressed to complete the book, the Swami would only say with his usual economy of words, ‘If the Master wills, he will have it done.’ One’s admiration for the Swami increases a thousandfold, if one knows the circumstances under which such a scholarly book was written. The house in which he lived was crowded. The Holy Mother was staying upstairs, and there was a stream of devotees coming at all hours of the day. There was the exacting duty of the secretaryship of the Ramakrishna Mission. Even in such a situation the Swami would be found absorbed in writing this book—giving a shape to his love and devotion to the Master and the Holy Mother in black and white—oblivious of the surroundings or any other thing in the world.

The ‘Udbodhan Office’ was removed to the new building towards the end of 1908 and the Holy Mother first came there on 23 May 1909. And what was Swami Saradananda’s joy when the Mother came and stayed in the house! For after Swami Yogananda’s demise and Swami Trigunatita’s departure for the West, Sharat Maharaj felt it his first duty to look after her comfort. To him she was actually a manifestation of the Divine Mother in human form, and he would make no distinction between her and the Master.

In 1909 a situation arose which showed how courageous this quiet-looking Swami was. Two of those who were accused of being revolutionaries connected with the Maniktala Bomb Case—Devavrata Bose and Sachindra Nath Sen came to join the Ramakrishna Order giving up their political activities. To accept them was to invite the wrath of the police and the Government. But to refuse admission to a sincere spiritual aspirant, simply because of his past conduct, was a sheer act of cowardice. Swami Saradananda accepted them and some other young men—political suspects—as members of the Order. He saw the police chief and other high officials in Calcutta and stood guarantee for these young men, all of whom amply repaid the Swami’s trust by their exemplary lives.

Some years later in the Administration Report of the Government of Bengal there was the insinuation that the writings of Swamiji were the source of inspiration behind the revolutionary activities in Bengal. And soon after, Lord Carmichael, the then Governor of Bengal, in his durbar speech at Calcutta in 1916 made some remarks with reference to the Ramakrishna Mission, which had a disastrous effect on its activities. To remedy the evil consequences, Swami Saradananda wrote to the Governor and saw the high officials and removed all misconceptions from their minds about the Mission’s activities.

However much he might try to ignore it, Swami Saradananda was passing through a great strain. As a result, he was not keeping well. Amongst other ailments he got rheumatism, for which the doctors advised a change to Puri where sea bathing would do him good.

The Swami went to Puri in March 1913, and returned in July. There also he did not stop his regular work. Throughout his stay at Puri he made it a rule to go to the temple of Jagannath every morning. During the Car Festival it was a sight for the gods to see a fat person like the Swami holding the rope of the Car and pulling it with great enthusiasm and devotion.

At Puri an incident happened which indicated the inborn courtesy and dignity of the Swami. Swami Saradananda with his party put up at ‘Shashi-Niketan’, a house belonging to the great devotee, the late Balaram Bose. One evening, the Swami on returning to the house after his usual walk, found that it had been occupied by the Raja of Bundi. This was due to the mistake of a priest-guide of the temple. The Swami could easily have asked the Raja to vacate the house. But to save the Raja as well as the guide from embarrassment the Swami agreed to remove to another house temporarily. Not knowing the real situation, the Private Secretary of the Raja at first showed some hauteur. But the reply and attitude of the Swami so much overpowered him, that he soon took the dust off the Swami’s feet as a mark of respect and veneration.

In 1913 there was a great flood in Burdwan. The Ramakrishna Mission started relief work under Swami Saradananda’s leadership; for his heart always bled for the poor and the afflicted. Whenever there was flood or famine the Swami would arrange for raising funds and see that proper workers went to the field of work. This Burdwan relief lasted for many months.

The next year the Swami was attacked by some kidney trouble. The pain was severe, but he bore it with wonderful fortitude. At that time the Holy Mother stayed upstairs. Lest she should become worried, the Swami would hardly give out that he had been suffering from any pain. Fortunately, after a few days, he came round.

In 1917 Swami Premananda fell ill of Kala-Azar. He stayed at the house of Balaram Bose in Calcutta, and Swami Saradananda supervised all arrangements for his treatment. Soon he had to rush to Puri, because Swami Turiyananda was seriously ill there. Whenever anybody in the Math was ill, Swami Saradananda was sure to be by his bedside. If he could not make time to attend the case personally, he would make all arrangements for the treatment. But if any emergency arose, the Swami was the person to meet it. If a patient does not like to take injection, Swami Saradananda would go there. Sometimes by his very presence the patient would change his mind. If a patient was clamouring for some food which would be injurious for him, the Swami in words of extreme love and sympathy, would say he would get the food he wanted, but after some days. The patient, like a child, would agree. There were instances when even in his busy life he passed the whole night by a sick-bed when the patient was difficult to manage. His sympathy was not limited to the members of the Order alone. Once a devotee fell ill of smallpox and was lying uncared for in a cottage on the Ganga. When the Swami heard of this he immediately went there and after careful nursing for a few days cured the patient.

In his old age, he could not personally attend on the patients. But the same love and sympathy were there. Once in his old age, he walked out alone at noon. Feeling anxious as to where he could go at such an odd hour, his attendant followed him. Soon he attracted the notice of the Swami, who at first asked him not to come, but at the latter’s earnest appeal allowed him to follow. The Swami went to a hotel and, entering a room upstairs, sat by the side of a patient. It was not difficult for the Swami’s attendant to understand that the man had tuberculosis. The Swami began to caress the patient lovingly, talking all the while in a tone of greatest sympathy. The patient was careless; as he talked, sputum fell on all sides. Now he got up, cut some fruits, and offered them to the Swami. While returning, the attendant took the liberty of blaming the Swami for eating there under such circumstances. The Swami at first remained quiet, and afterwards said, ‘The Master used to say, ‘it will not do you any harm if you take food offered with love and devotion.’

From 1920 onward the Swami sustained such heavy bereavements that he became altogether broken in heart. In 1920 the Holy Mother passed away. And two years later Swami Brahmananda followed her. There were other deaths too. Brother disciples were passing away. He began to feel lonely in this world. Gradually he began to withdraw his mind from work and to devote greater and greater time to meditation. Those who watched him could easily see that he was preparing for the final exit.

At this time one task which received his most serious attention was the construction of a temple at Jayrambati in sacred memory of the Holy Mother. He would supply money and supervising hands for the work and keep himself acquainted with the minutest details of the construction. He would openly say that after the completion of the temple he would retire from all work. The beautiful temple—emblem of Swami Saradananda’s devotion to the Holy Mother—was dedicated on 19 April 1923.

Another very important work which the Swami did and which will go down in history was the holding of the Ramakrishna Mission Convention at Belur Math in 1926. It was mainly a meeting of the monks of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission centres—about one hundred in number, sprinkled over the whole of India as well as outside India—in order to compare notes and devise future plans of work.

Though not keeping very well, he took great interest in it and worked very hard to make it a success. In the Address of Welcome that the Swami delivered at the first session of the convention he surveyed the past of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission in a sweep, very frankly depicted the present position, and warned the members against the dangers and pitfalls that were lurking in the future. Every new movement passes through three stages—opposition, indifference, and acceptance. There is great opposition when a new movement is started. If it has the strength to stand the opposition, the public accepts it and showers praise and admiration. Then comes the real danger for the movement. ‘For security brings a relaxation of spirits and energy, and a sudden growth of extensity quickly lessens the intensity and unity of purpose that were found among the promoters of the movement.’ The whole speech was full of fire and vigour. It was like a veteran General’s charge to his present army and future unknown soldiers.

Mahasamadhi

After the convention, the Swami virtually retired from active work, devoting more and more time to meditation. With his ill health, finding him devoted so much to meditation and spiritual practices, the doctors got alarmed and raised objections. And after all what was the necessity of any further spiritual practices for a soul like Swami Saradananda! But to all protests the Swami would simply give a loving smile.

It was Saturday, 6 August 1927. Swami Saradananda, as usual, sat in meditation in his room early in the morning. Generally he would be meditating till past noon. But that day he left meditation earlier and entered the shrine. He remained in the shrine for about twenty-five minutes—an unusually long period, and then returned to the door. Again he entered, stood for a few moments near the portrait of the Holy Mother, and returned. This he did several times. When he finally came out, a great serenity shone through his face. He followed his other routines of the day as usual. In the evening, when the usual service was going on in the shrine, he remained absorbed in thought in his own room. After that an attendant came with some papers. As the Swami stood up to put them inside a chest of drawers, he felt uneasy, his head reeled, as it were. He asked the attendant to prepare some medicine and instructed him to keep the news secret lest it should create unnecessary alarm. These were the last words, and he lay down on the bed. It was a case of apoplexy. The Swami passed away at 2.34 a.m. of 19 August.

Swami Saradananda was the living embodiment of the ideal of the Gita in the modern age. To see him was to know how a man can be ‘Sthitaprajna’—steadfast in wisdom—as taught in the Gita. He was alike in heat and cold, praise and blame, nay, his life was tuned to such a high pitch that he was beyond the reach of such things. In spite of all his activities, one could tangibly see that his was the case of a Yogi ‘whose happiness is within, whose relaxation is within, and whose light is within’. He harmonized in his life Jnana, Karma, Bhakti, and Yoga, and it was difficult to find out which was less predominant in him. Everyone of these four paths reached the highest perfection in him, as it were.

We find Swami Saradananda mainly in two roles—as the Secretary of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission and as a spiritual personality. As the Secretary of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission he was so much in the love and esteem of the workers that his slightest desire was fulfilled with utmost veneration. And this love and esteem was the effect of the Swami’s extreme solicitude for their welfare and his unreserved confidence in them. It was very difficult to prejudice him against anybody. And his confidence and trust were never betrayed. He was very democratic in attitude and always kept an open mind. Even to the words of a boy he would listen with great attention and patience. When at any time he found that he had committed a mistake, he would not hesitate to acknowledge it immediately. Once he took a young monk to task for a supposed fault. Afterwards when the Swami knew that the monk was not really at fault, he felt so sorry that he tenderly apologized. Though wielding so much power, he had not the slightest love of power in him. He was humility itself. He felt that anyone might know better than he. His idea was that everyone was striving after Ultimate Freedom, and that such hankering expressed itself in the love of freedom in daily action. So the Swami would not willingly disturb anybody’s freedom.

It must not, however, be forgotten that the secret of his power and influence was his spiritual personality. It was only because spiritually he belonged to a very high plane that he could love one and all so unselfishly, remain unmoved in all circumstances, and keep his faith in humanity under all trials. It is difficult to gauge the spiritual depth of a person from outside, especially of a soul like Swami Saradananda who would overpower a person by his very presence. This much we know that hundreds of persons would come and look up to him for spiritual solace when they became weary of the world or torn with conflict and affliction. And whoever came in touch with him could not help becoming nobler and spiritually richer. Records in his personal diary show that he had communion with the Divine Mother on many occasions, but more than that people would tangibly feel that here was one whose will was completely identified with the will of God. It was because of this perhaps that one or two words from his lips would remove a heavy burden from many a weary heart. Once an attendant, who felt the touch of his love so much that often he could dare to take liberty with him, asked him what he had attained spiritually. The Swami only replied, ‘Did we merely vegetate at Dakshineswar?’ At another time, quite inadvertently, he gave out to this attendant that whatever he had written in Sri Ramakrishna Lilaprasanga about spiritual things, he had experienced directly in his own life. And in that book he has at places delineated the highest experiences of spiritual life.

But with all his spiritual attainment, the Swami was quite modern in outlook. Those who did not believe or had no interest in religion would find joy in mixing with him as a very cultured man. He was in touch with all modern thoughts and movements. This aspect of his life drew many to him, who would afterwards be gradually struck by his spirituality.