Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 92:

yesaṃ sannicayo natthi ye pariññātabhojanā |

suññato animitto ca vimokkho yesa gocarā |

ākāse’va sakuntānaṃ gati tesaṃ durannayā || 92 ||

92. For those who don’t accumulate, who well reflect upon their food, they have as range the nameless and the void of perfect freedom too. As birds that wing through space, hard to trace their going.

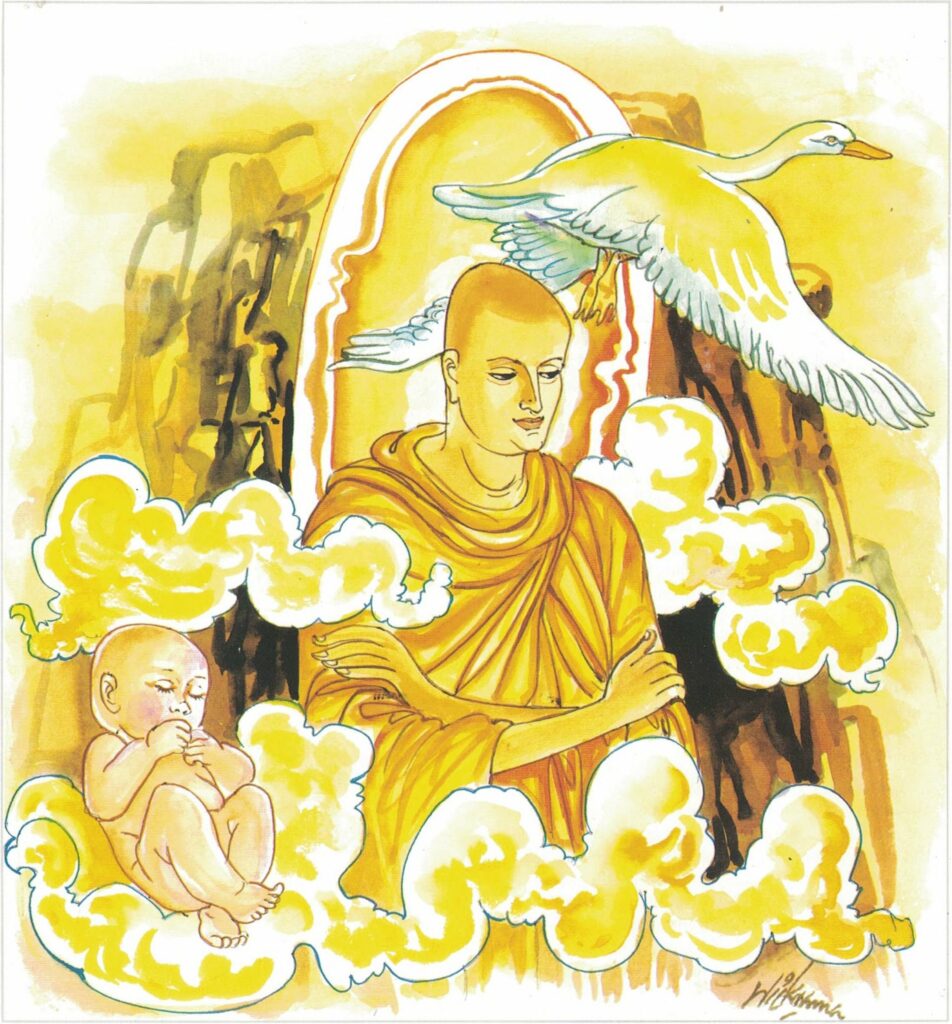

The Story of Venerable Bellaṭṭhisīsa

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to Venerable Bellaṭṭhisīsa.

Venerable Bellaṭṭhisīsa, after going on an alms-round in the village, stopped on the way and took his food there. After the meal, he continued his round of alms for more food. When he had collected enough food he returned to the monastery, dried up the rice and hoarded it. Thus, there was no need for him to go on an alms-round every day; he then remained in jhāna (one-pointed) concentration for two or three days. Arising from jhāna concentration he ate the dried rice he had stored up, after soaking it in water. Other monks thought ill of the thera on this account, and reported to the Buddha about his hoarding of rice. Since then, the hoarding of food by the monks has been prohibited.

As for Venerable Bellaṭṭhisīsa, since he stored up rice before the ruling on hoarding was made and because he did it not out of greed for food, but only to save time for meditation practice, the Buddha declared that the thera was quite innocent and that he was not to be blamed.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 92)

yesaṃ sannicayo natthi ye pariññatabhojanā

yassa suññato animitto vimokkho ca gocaro

tesaṃ gati ākāse sakuntānaṃ iva durannayā

yesaṃ [yesa]: to those (liberated persons); sannicayo natthi: there is no amassing; ye: they; pariññatabhojanā: full of understanding of the nature of food; yassa: to whom; suññato [suññata]: emptiness; animitto [animitta]: objectlessness; vimokkho [vimokkha]: freedom of mind; ca gocaro [gocara]: are the field; tesaṃ gati: their whereabouts; ākāse sakuntānaṃ iva: like the birds in the sky; durannayā: are difficult to be perceived or known

With full understanding that nature is empty and objectless the mind is free of craving and leaves no trace of its whereabouts like the paths of birds in flight.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 92)

sannicayo natthi: no hoarding. The evolved persons–the saintly individuals–do not hoard anything. This statement is true in two ways. It is quite clear that they do not hoard worldly requisites and material things. They do not also accumulate fresh merit or sin. They do not accumulate new Kamma. Because of that they do not have a rebirth. An arahat may commit an act of virtue. He does not accumulate new merit for that act.

arahat: This stanza dwells on the special qualities of an arahat. Who, then, are the arahats? They are those who cultivate the path and reach the highest stage of realization (arahatta), the final liberation from suffering.

Victors like me are they, indeed,

They who have won defilements’ end.

Arahats have given up all attachments, even the subtlest. Therefore, an arahat’s mind roams only on emptiness, objectlessness and total freedom of thought.

The Buddha, however, also made clear to his disciples the difference between himself and the arahats who were his disciples. They were declared by the Buddha to be his equals as far as the emancipation from defilements and ultimate deliverance are concerned:

‘The Buddha, O disciples, is an Arahat, a fully Enlightened One. It is

He who proclaims a path not proclaimed before, He is the knower of a path, who understands a path, who is skilled in a path. And now His disciples are way-farers who follow in His footsteps. That is the distinction, the specific feature which distinguishes the Buddha, who is an Arahat; a Fully Enlightened One, from the disciple who is freed by insight.’ Sanskrit arhat ‘the Consummate One’, ‘The Worthy One’: are titles applied exclusively to the Buddha and the perfected disciples. As the books reveal, the first application of the term to the Buddha was by himself. That was when the Buddha was journeying from Gayā to Bārānasi to deliver his first sermon to the five ascetics. On the way, not far from Gayā, the Buddha was met by Upaka, an ascetic, who, struck by the serene appearance of the Master, inquired: ‘Who is thy teacher? Whose teaching do you profess?’

Replying in verse, the Buddha said:

‘I, verily, am the Arahat in the world,

A teacher peerless am I…’

He used the word for the second time when addressing the five ascetics thus: ‘I am an Arahat, a Tathāgata, fully enlightened.’

The word is applied only to those who have fully destroyed the taints. In this sense, the Buddha was the first Arahat in the world as he himself revealed to Upaka.