Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 85-86:

appakā te manussesu ye janā pāragāmino |

athāyaṃ itarā pajā tīramevānudhāvati || 85 ||

ye ca kho sammadakkhāte dhamme dhammānuvattino |

te janā pāramessanti maccudheyyaṃ suduttaraṃ || 86 ||

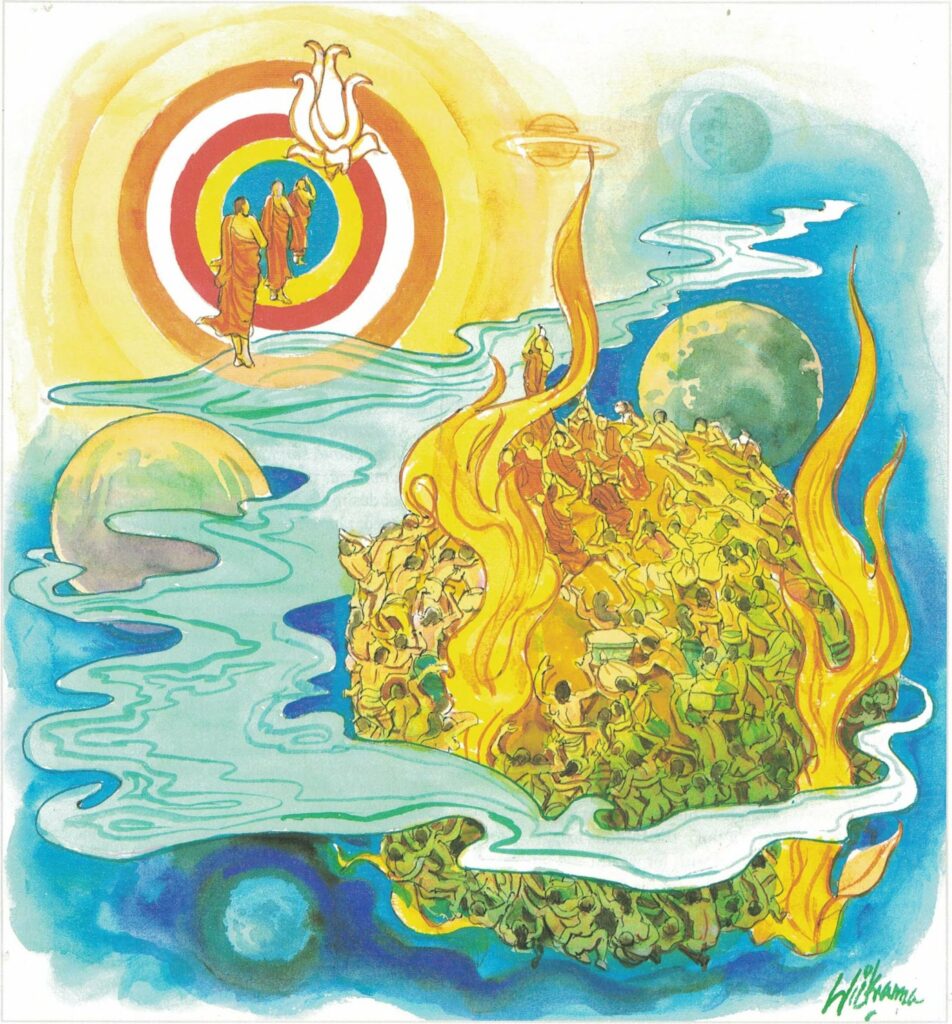

85. Among folk they are few who go to the Further Shore, most among humanity scurry on this hither shore.

86. But they who practise Dhamma according to Dhamma well-told, from Death’s Dominion hard to leave they’ll cross to the Further Shore.

The Story of Dhamma Listeners

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to a congregation of people who had come to listen to a religious discourse in Sāvatthi. On one occasion, a group of people from Sāvatthi made special offerings to the monks collectively and they arranged for some monks to deliver discourses throughout the night, in their locality. Many in the audience could not sit up the whole night and they returned to their homes early; some sat through the night, but most of the time they were drowsy and half-asleep. There were only a few who listened attentively to the discourse.

At dawn, when the monks told the Buddha about what happened the previous night, he replied, “Most people are attached to this world; only a very few reach the other shore (nibbāna).”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 85)

manussesu ye janā pāragāmino te appakā

athā itarā ayaṃ pajā tīraṃ eva anudhāvati

manussesu: of the generality of people; ye janā: those who; pāragāmino [pāragāmina]: cross over to the other shore; ti: they; appakā: (are) only a few; athā: but; itarā: the other; ayaṃ pajā: these masses; tīraṃ eva: on this shore itself; anudhāvati: keep running along

Of those who wish to cross over to the other side only a handful are successful. Those others who are left behind keep running along this shore. Those masses who have not been able to reach liberation continue to be caught up in Saṃsāra.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 86)

ye ca kho sammadakkhāte dhamme dhammānuvattino

te janā suduttaraṃ maccudheyyaṃ pāraṃ essanti

ye ca kho: whosoever; sammadakkhāte: in the well articulated;dhamme: teaching; dhammānuvattino [dhammānuvattina]: who live in accordance with the Teaching; te janā: those people; suduttaraṃ [suduttara]: difficult to be crossed; maccudheyyaṃ [maccudheyya]: the realm of death; pāraṃ essanti: cross over

The realms over which Māra has sway are difficult to cross. Only those who quite righteously follow the way indicated in the well-articulated Teachings of the Buddha, will be able to cross these realms that are so difficult to cross.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 85-86)

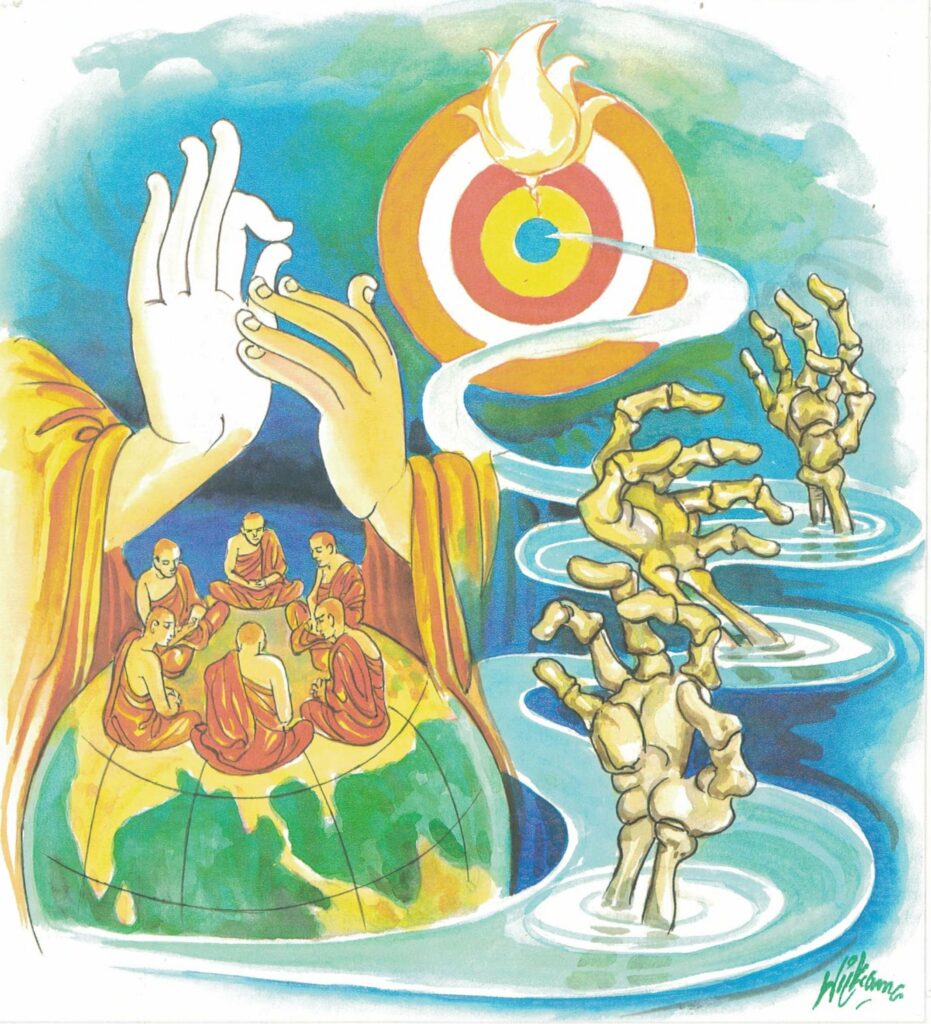

Dhamme Dhammānuvattino: the teaching of the Buddha and those who practice the Teaching. The Buddha expounded his Teaching, initially, to the Five Ascetics and preached his first sermon–“The Turning of the Wheel of Truth”. Thus did the Enlightened One proclaim Dhamma and set in motion the matchless “Wheel of Truth”. With the proclamation of the Dhamma, for the first time, and with the conversion of the five ascetics, the Deer Park at Isipatana became the birth place of the Buddha’s Dispensation, and of the Sangha, the community of monks, the ordained disciples. The Buddha addressed his disciples, the accomplished ones (arahats), and said: “Released am I, monks, from all ties whether human or divine. You also are delivered from fetters whether human or divine. Go now and wander for the welfare and happiness of many, out of compassion for the world, for the gain, welfare and happiness of gods and men. Let not two of you proceed in the same direction. Proclaim the Dhamma that is excellent in the beginning, excellent in the middle, excellent in the end, possessed of the meaning and the letter both utterly perfect. Proclaim the life of purity, the holy life consummate and pure. There are beings with little dust in their eyes who will be lost through not hearing the Dhamma. There are beings who will understand the Dhamma. I also shall go to Uruvelā, to Senānigama to teach the Dhamma. Thus did the Buddha commence his sublime mission which lasted to the end of his life. With his disciples he walked the highways and byways of Jambudīpa, land of the rose apple (another name for India), enfolding all within the aura of his boundless compassion and wisdom. The Buddha made no distinction of caste, clan or class when communicating the Dhamma. Men and women from different walks of life–the rich and the poor; the lowliest and highest; the literate and the illiterate; brāhmins and outcasts, princes and paupers, saints and criminals–listened to the Buddha, took refuge in him, and followed him who showed the path to peace and enlightenment. The path is open to all. His Dhamma was for all. Caste, which was a matter of vital importance to the brāhmins of India, was one of utter indifference to the Buddha, who strongly condemned so debasing a system. The Buddha freely admitted into the Sangha people from all castes and classes, when he knew that they were fit to live the holy life, and some of them later distinguished themselves in the Sangha. The Buddha was the only contemporary teacher who endeavoured to blend in mutual tolerance and concord those who hitherto had been rent asunder by differences of caste and class. The Buddha also raised the status of women in India. Generally speaking, during the time of the Buddha, owing to brahminical influence, women were not given much recognition. Sometimes they were held in contempt, although there were solitary cases of their showing erudition in matters of philosophy, and so on. In his magnanimity, the Buddha treated women with consideration and civility, and pointed out to them, too, the path to peace, purity and sanctity. The Buddha established the order of nuns (Bhikkhunī Sāsana) for the first time in history; for never before this had there been an order where women could lead a celibate life of renunciation. Women from all walks of life joined the order. The lives of quite a number of these noble nuns, their strenuous endeavours to win the goal of freedom, and their paeans of joy at deliverance of mind are graphically described in the ‘Psalms of the Sisters’ (Therīgāthā).

While journeying from village to village, from town to town, instructing, enlightening and gladdening the many, the Buddha saw how superstitious folk, steeped in ignorance, slaughtered animals in worship of their gods.

He spoke to them:

Of life, which all can take but none can give,

Life which all creatures love and strive to keep,

Wonderful, dear and pleasant unto each,

Even to the meanest…

The Buddha never encouraged wrangling and animosity. Addressing the monks he once said: “I quarrel not with the world, monks, it is the world that quarrels with me. An exponent of the Dhamma quarrels not with anyone in the world.”

To the Buddha the practice of the Dhamma is of great importance. Therefore, the Buddhists have to be Dhammānuvatti (those who practice the Teaching). The practical aspects are the most essential in the attainment of the spiritual goals indicated by the Buddha’s Dhamma (Teaching).

There are no shortcuts to real peace and happiness. As the Buddha has pointed out in many a sermon this is the only path which leads to the summit of the good life, which goes from lower to higher levels of the mental realm. It is a gradual training, a training in speech, deed and thought which brings about true wisdom culminating in full enlightenment and the realization of Nibbāna. It is a path for all, irrespective of race, class or creed, a path to be cultivated every moment of our waking life.

The one and only aim of the Buddha in pointing out this Teaching is stated in these words: “Enlightened is the Buddha, He teaches the Dhamma for enlightenment;tamed is the Buddha, He teaches the Dhamma for taming; calmed is the Buddha, He teaches the Dhamma for calming; crossed over has the Buddha, He teaches the Dhamma for crossing over; attained to Nibbāna has the Buddha, He teaches the Dhamma for attainment of Nibbāna.”

This being the purpose for which the Buddha teaches the Dhamma, it is obvious that the aim of the listener or the follower of that path should also be the same, and not anything else. The aim, for instance, of a merciful and understanding physician should be to cure the patients that come to him for treatment, and the patient’s one and only aim, as we know, is to get himself cured as quickly as possible. That is the only aim of a sick person.

We should also understand that though there is guidance, warning and instruction, the actual practice of the Dhamma, the treading of the path, is left to us. We should proceed with undiminished vigour surmounting all obstacles and watching our steps along the right Path–the very path trodden and pointed out by the Buddhas of all ages.

To explain the idea of crossing over, the Buddha used the simile of a raft: “Using the simile of a raft, monks, I teach the Dhamma designed for crossing over and not for retaining.”

The Buddha, the compassionate Teacher, is no more, but he has left a legacy, the sublime Dhamma. The Dhamma is not an invention, but a discovery. It is an eternal law; it is everywhere with each man and woman, Buddhist or non-Buddhist, Eastern or Western. The Dhamma has no labels, it knows no limit of time, space or race. It is for all time. Each person who lives the Dhamma sees its light, sees and experiences it himself. It cannot be communicated to another, for it has to be self-realised.

Kamma: action, correctly speaking denotes the wholesome and unwholesome volitions and their concomitant mental factors, causing rebirth and shaping the destiny of beings. These karmical volitions become manifest as wholesome or unwholesome actions by body, speech and mind. Thus the Buddhist term kamma by no means signifies the result of actions, and quite certainly not the fate of man, or perhaps even of whole nations (the so-called wholesale or mass-karma), which misconceptions have become widely spread in some parts of the world. Said the Buddha, “Volition, O Monks, is what I call action, for through volition one performs the action by body, speech or mind. There is Kamma, O Monks, that ripens in hell. Kamma that ripens in the animal world. Kamma that ripens in the world of men. Kamma that ripens in the heavenly world. Three-fold, however, is the fruit of kamma: ripening during the life-time, ripening in the next birth, ripening in later births.

The three conditions or roots of unwholesome kamma (actions) are: Greed, Hatred, Delusion; those of wholesome kamma are: Unselfishness, Hatelessness (goodwill), Non-delusion.

(See also: Bhagavad Gita 16.21)

“Greed is a condition for the arising of kamma, Hatred is a condition for the arising of kamma, Delusion is a condition for the arising of kamma”.

“The unwholesome actions are of three kinds, conditioned by greed, or hate, or delusion.”

“Killing, stealing, unlawful sexual intercourse, lying, slandering, rude speech, foolish babble, if practiced, carried on, and frequently cultivated, lead to rebirth in hell, or amongst the animals, or amongst the ghosts.” “He who kills and is cruel goes either to hell or, if reborn as man, will be short-lived. He who torments others will be afflicted with disease. The angry one will look ugly, the envious one will be without influence, the stingy one will be poor, the stubborn one will be of low descent, the indolent one will be without knowledge. In the contrary case, man will be reborn in heaven or reborn as man, he will be longlived, possessed of beauty, influence, noble descent and knowledge.”

“Owners of their kamma are the beings, heirs of their kamma. The kamma is the womb from which they are born, their kamma is their friend, their refuge. Whatever kamma they perform, good or bad, thereof they will be the heirs.”

Kilesa: defilements–mind-defiling, unwholesome qualities. “There are ten defilements, thus called because they are themselves defiled, and because they defile the mental factors associated with them.

They are:

- greed;

- hate;

- delusion;

- conceit;

- speculative views;

- skeptical doubt;

- mental torpor;

- restlessness;

- shamelessness;

- lack of moral dread or unconsciousness.

Vipāka: karma-result–is any karmically (morally) neutral mental phenomenon (e.g., bodily agreeable or painful feeling, sense-consciousness etc.), which is the result of wholesome or unwholesome volitional action through body, speech or mind, done either in this or some previous life. Totally wrong is the belief that, according to Buddhism, everything is the result of previous action. Never, for example, is any karmically wholesome or unwholesome volitional action (kamma), the result of former action, being in reality itself kamma.

Karma-produced corporeal things are never called kamma-vipāka, as this term may be applied only to mental phenomena.