Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 368-376:

mettāvihārī yo bhikkhū pasanno buddhasāsane |

adhigacche padaṃ santaṃ saṅkhārū’pasamaṃ sukhaṃ || 368 ||

siñca bhikkhu imaṃ nāvaṃ sittā te lahumessati |

chetvā rāgaṃ dosaṃ ca tato nibbāṇamehisi || 369 ||

pañca chinde pañca jahe pañca c’uttari bhāvaye |

pañca saṅgātigo bhikkhu oghatiṇṇo’ti vuccati || 370 ||

jhāya bhikkhu mā ca pāmado mā te kāmaguṇe bhamassu cittaṃ |

mā lohaguḷaṃ gilī pamatto mā kandi dukkham idan’ti ḍayhamāno || 371 ||

natthi jhānaṃ apaññassa paññā natthi ajhāyato |

yamhi jhānaṃ ca paññā ca sa ve nibbāṇasantike || 372 ||

suññāgāraṃ paviṭṭhassa santacittassa bhikkhuno |

amānusī rati hoti sammā dhammaṃ vipassato || 373 ||

yato yato sammasati khandhānaṃ udayabbayaṃ |

labhati pītipāmojjaṃ amataṃ taṃ vijānataṃ || 374 ||

tatrāyam ādi bhavati idha paññassa bhikkhuno |

indriyagutti santuṭṭhī pātimokkhe ca saṃvaro |

mitte bhajassu kalyāṇe suddhājīve atandite || 375 ||

paṭisanthāravutty’assa ācārakusalo siyā |

tato pāmojjabahulo dukkhassantaṃ karissasi || 376 ||

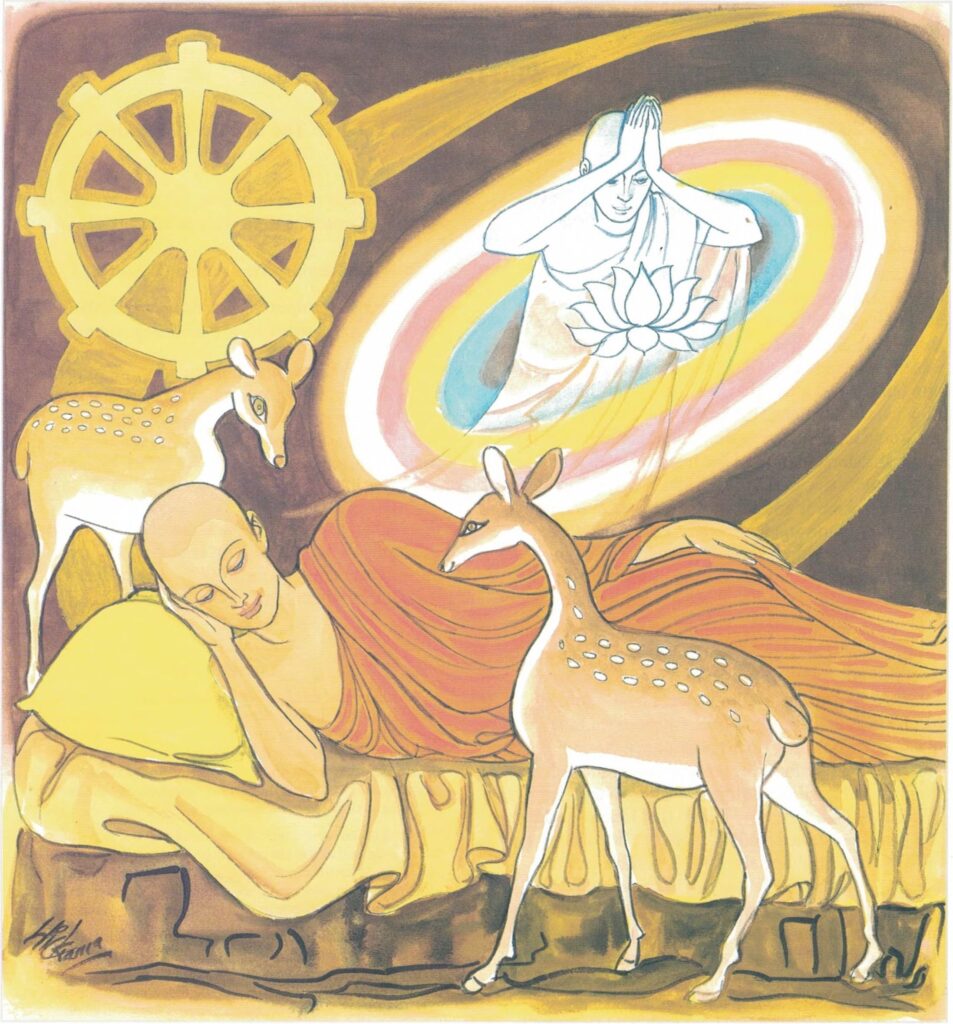

368. The bhikkhu in kindness abiding, bright in the Buddha’s Teaching can come to the Place of Peace, the bliss of conditionedness ceased.

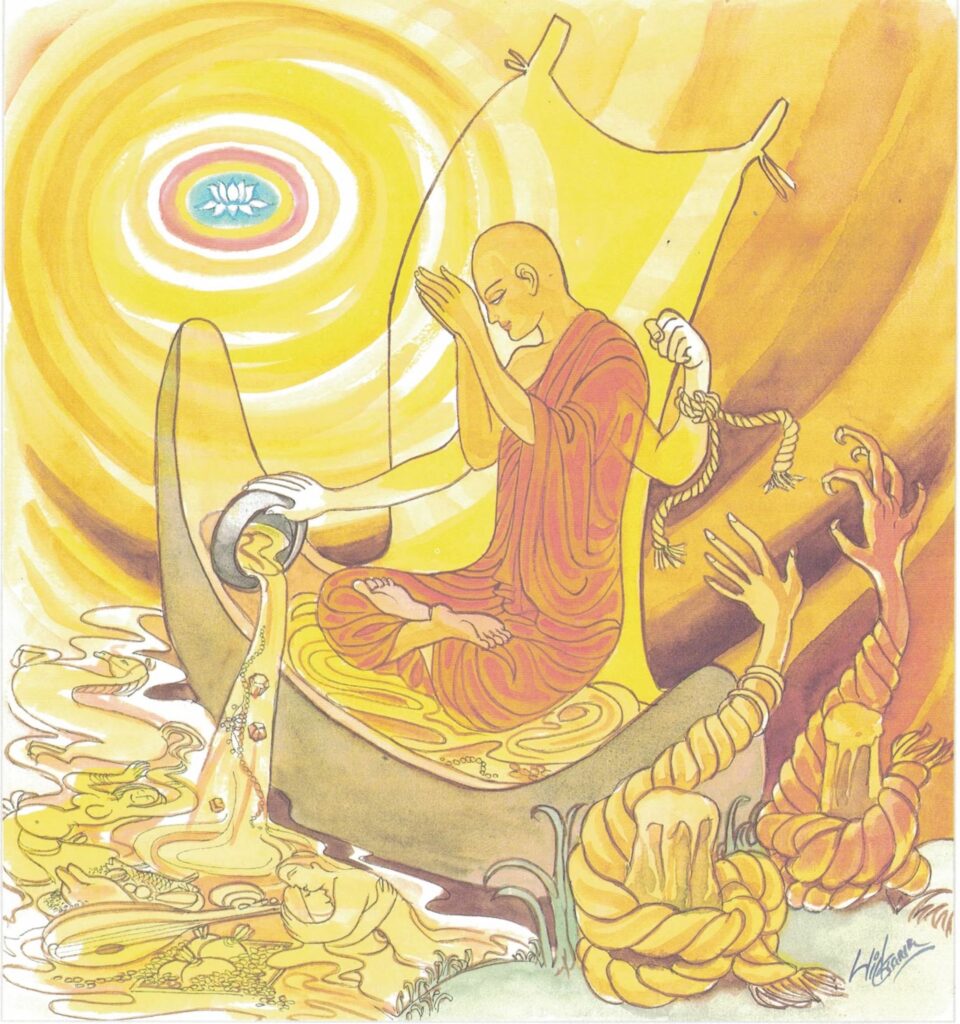

369. O bhikkhu bail this boat, when emptied it will swiftly go. Having severed lust and hate thus to Nibbāna you’ll go.

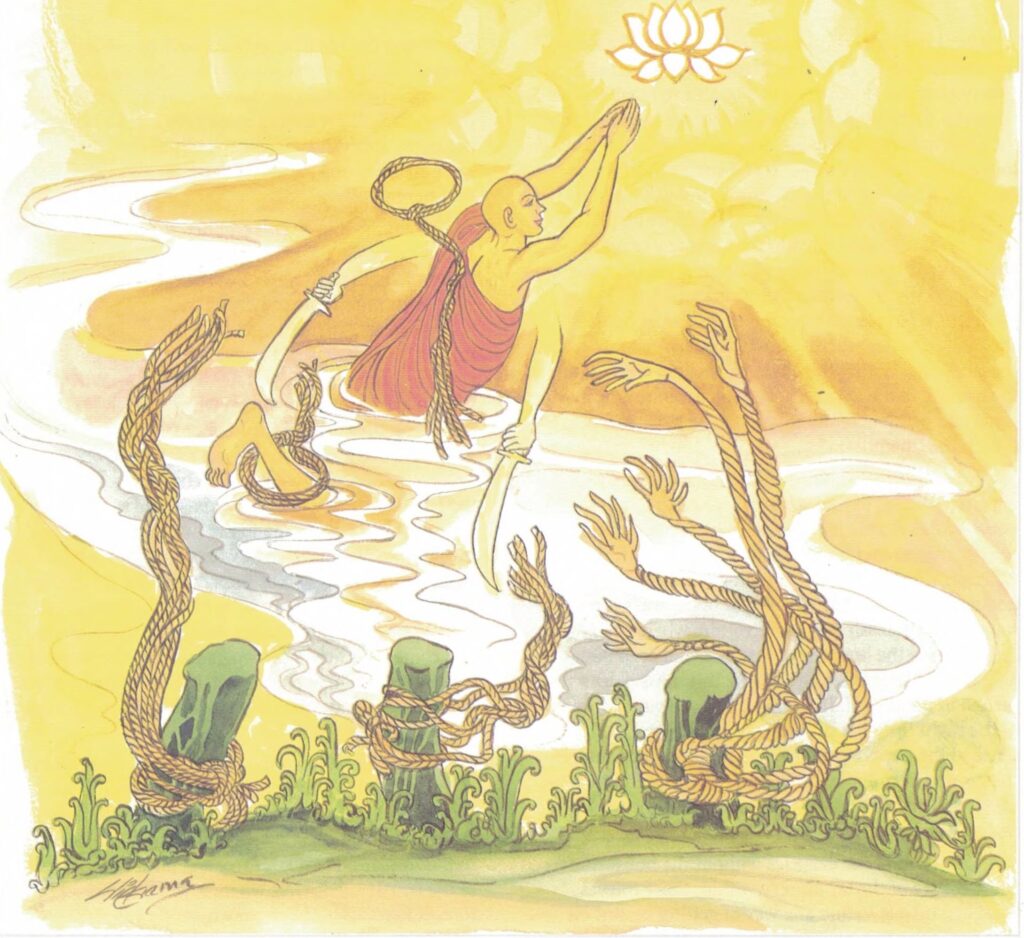

370. Five cut off and five forsake, a further five then cultivate, a bhikkhu from five fetters free is called a ‘Forder of the flood’.

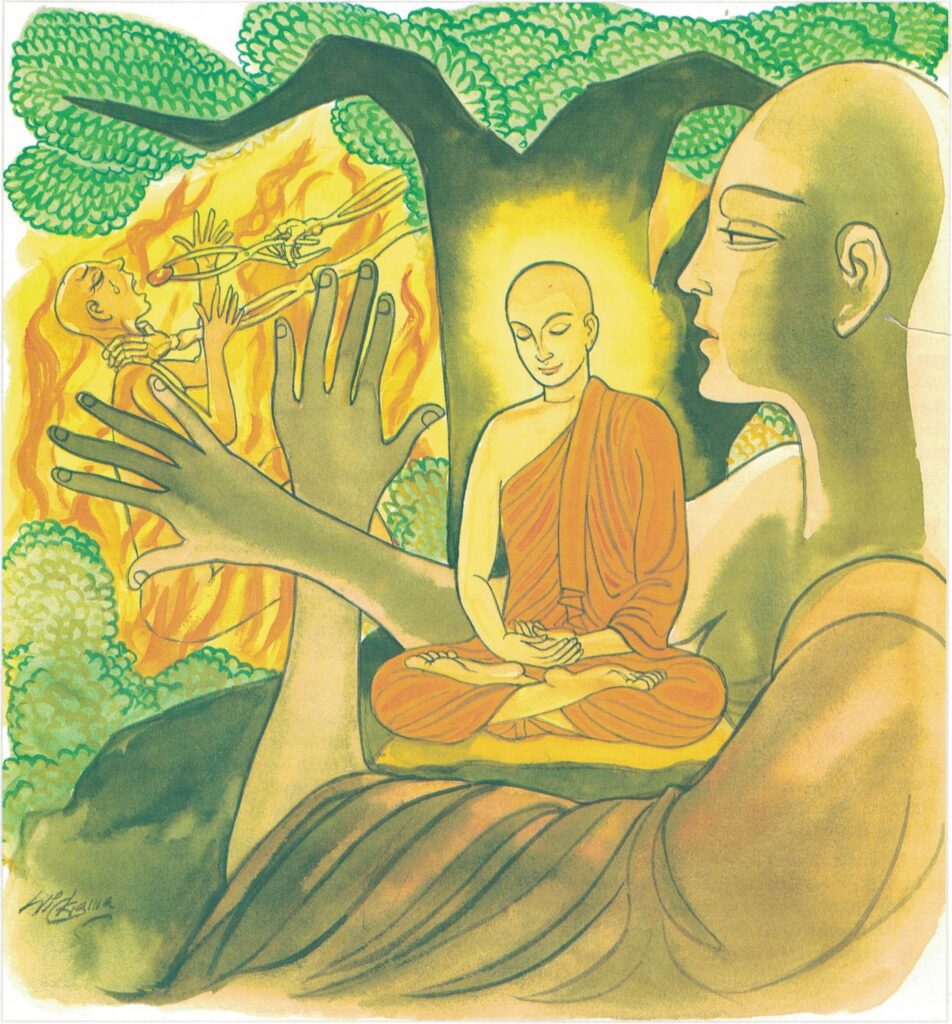

371. Meditate bhikkhu! Don’t be heedless! Don’t let pleasures whirl the mind! Heedless, do not gulp a glob of iron! Bewail not when burning, ‘This is dukkha’!

372. No concentration wisdom lacks, no wisdom concentration lacks, in whom are both these qualities near to Nibbāna is that one.

373. The bhikkhu gone to a lonely place who is of peaceful heart in-sees Dhamma rightly, knows all-surpassing joy.

374. Whenever one reflects on aggregates’ arise and fall one rapture gains and joy. ’Tis Deathlessness for Those-who-know.

375. Here’s indeed the starting-point for the bhikkhu who is wise, sense-controlled, contented too, restrained to limit freedom ways, in company of noble friends who’re pure of life and keen.

376. One should be hospitable and skilled in good behaviour, thereby greatly joyful come to dukkha’s end.

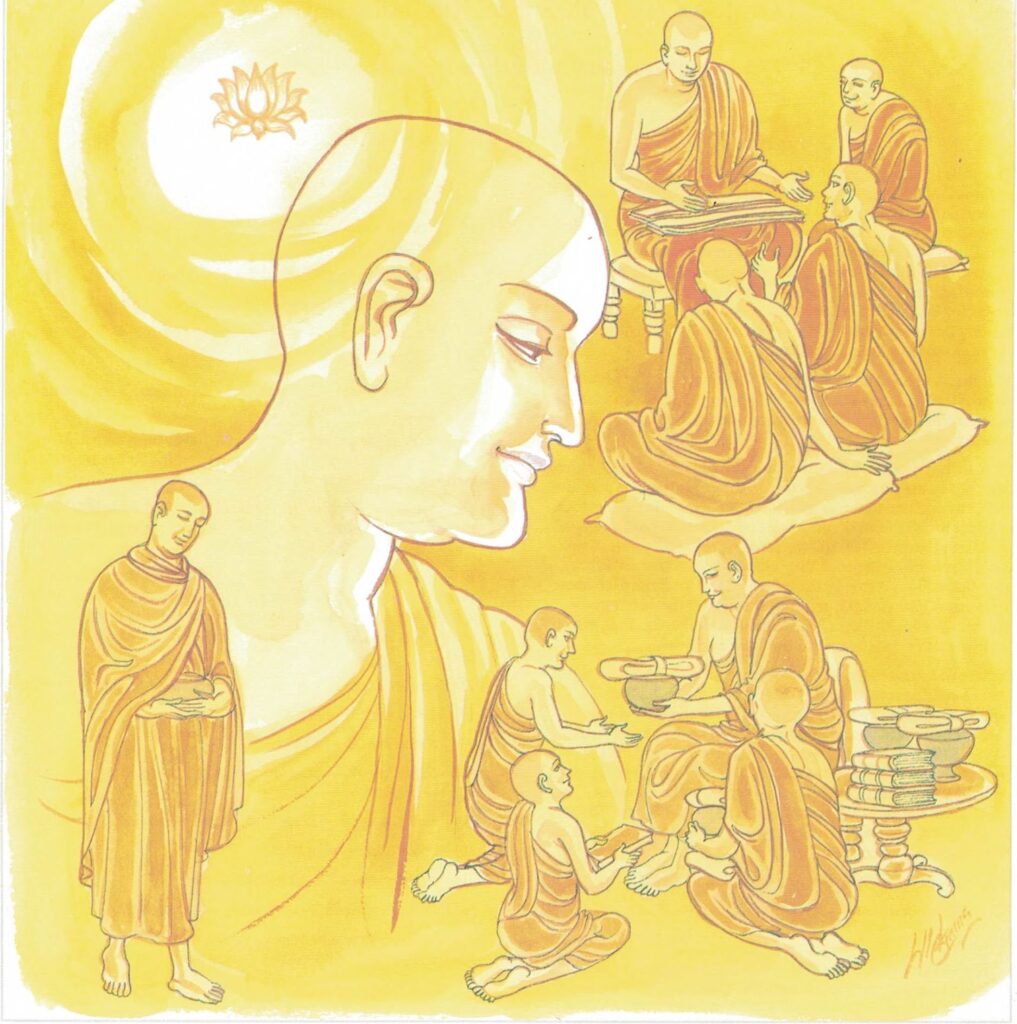

The Story of a Devout Lady and the Thieves

Once upon a time, while Venerable Mahā Kaccāna was in residence in the Avanti country on a mountain near the city of Kurāraghāra, a lay disciple named Soṇa Kūṭikaṇṇa, convinced of the truth of the Dhamma by the preaching of the monk, expressed a desire to retire from the world and become a monk under him. The Venerable kept saying, “Soṇa, it is a difficult matter to eat alone and lodge alone and live a life of chastity,” and twice turned him away.

But Soṇa was determined to become a monk, and on asking the Venerable the third time, succeeded in obtaining admission to the Sangha. On account of the scarcity of monks in the South, he spent three years in that country, and then made his full profession as a member of the Sangha. Desiring to see the Buddha face to face, he asked leave of his preceptor, and taking a message from him, set out for Jetavana Monastery. On reaching Jetavana, he saluted the Buddha, who greeted him in a friendly manner and permitted him to lodge in the perfumed chamber alone with himself.

Soṇa spent the greater part of the night in the open air, and then, entering the perfumed chamber, spent the rest of the night on the couch assigned to him for his own use. When the dawn came, he intoned by command of the Buddha all of the sixteen octads. When he had completed his recitation of the text, the Buddha thanked him and applauded him, saying, “Well done, well done, monk!” Hearing the applause bestowed upon him by the Buddha, the deities, beginning with deities of the earth, nāgas and the supaṇṇas, and extending to the world of brahmā, gave one shout of applause.

At that moment also the deity resident in the house of the eminent female lay disciple who was the mother of the Venerable Soṇa in Kurāraghāra city, at a distance of a hundred and twenty leagues from the Jetavana, gave a loud shout of applause. The female lay disciple said to the deity, “Who is this that gives applause?” The deity replied, “It is I, sister.” “Who are you?” “I am the deity resident in your house.” “You have never before bestowed applause upon me; why do you do so today?” “I am not bestowing applause upon you.” “Then upon whom are you bestowing applause?” “Upon your son Venerable Kūṭikaṇṇa Soṇa.” “What has my son done?”

“Today, your son, residing alone with the Buddha in the perfumed chamber, recited the Dhamma to the Buddha. The Buddha, pleased with your son’s recitation of the Dhamma, bestowed applause upon him; therefore I also bestowed applause upon him. For when the deities heard the applause bestowed upon your son by the Buddha, all of them, from deities of earth to the world of brahma, gave one shout of applause.” “Master, do you really mean that my son recited the Dhamma to the Buddha? Did not the Buddha recite the Dhamma to my son?” “It was your son who recited the Dhamma to the Buddha.”

As the deity thus spoke, the five kinds of joy sprang up within the disciple, suffusing her whole body. Then the following thought occurred to her, “If my son has been able, residing alone with the Buddha in the perfumed chamber, to recite the Dhamma to him, he will be able to recite the Dhamma to me also. When my son returns, I will arrange for a hearing of the Dhamma and will listen to his preaching of the Dhamma.”

When the Buddha bestowed applause upon Venerable Soṇa, the Venerable thought to himself, “Now is the time for me to announce the message which my preceptor gave me.” Accordingly Venerable Soṇa asked the Buddha for five boons, asking first for full admission to the Sangha community of five monks in the borderlands, of whom one was a monk versed in the Vinaya. For a few days longer he resided with the Buddha, and then, thinking to himself, “I will now go see my preceptor,” took leave of the Buddha, departed from the Jetavana Monastery, and in due course arrived at the abode of his preceptor.

On the following day Venerable Kaccāna took Venerable Soṇa with him and set out on his round for alms, going to the door of the house of the female lay disciple who was the mother of Soṇa. When the mother of Soṇa saw her son, her heart was filled with joy. She showed him every attention and asked him, “Dear son, is the report true that you resided alone with the Buddha in the perfumed chamber, and that you recited the Dhamma to the Buddha?” “Lay disciple, who told you that?” “Dear son, the deity who resides in this house gave a loud shout of applause, and when I asked, ‘Who is this that gives applause?’ the deity replied, ‘It is I,’ and told thus and so.”

“After I had listened to what he had to say, the following thought occurred to me, ‘If my son has recited the Dhamma to the Buddha, he will be able to recite the Dhamma to me also.’ Dear son, since you have recited the Dhamma to the Buddha, you will be able to recite it to me also. Therefore on such and such a day I will arrange for a hearing of the Dhamma, and will listen to your preaching of the Dhamma.” He consented. The female lay disciple gave alms to the company of monks and rendered honour to them. Then she said to herself, I will hear my son preach the Dhamma.” And leaving but a single female slave behind to guard the house, she took all of her attendants with her and went to hear the Dhamma. Within the city, in a pavilion erected for the hearing of the Dhamma, her son ascended the gloriously adorned seat of the Dhamma and began to preach the Dhamma.

Now at this time nine hundred thieves were prowling about, trying to find some way of getting into the house of this female lay disciple. As a precaution against thieves, her house was surrounded with seven walls, provided with seven battlemented gates, and at frequent intervals about the circuit of the walls were savage dogs on leashes. Moreover within, where the water dripped from the house-roof, a trench had been dug and filled with lead. In the daytime this mass of lead melted in the rays of the sun and became viscous, and in the night time the surface became stiff and hard. Close to the trench, great iron pickets had been sunk in the ground in unbroken succession. Such were the precautionary measures against thieves taken by this female lay disciple.

By reason of the defenses without the house and the presence of the lay disciple within, those thieves had been unable to find any way of getting in. But on that particular day, observing that she had left the house, they dug a tunnel under the leaden trench and the iron pickets, and thus succeeded in getting into the house. Having effected an entrance into the house, they sent the ringleader to watch the mistress of the house, saying to him, “If she hears that we have entered the house, and turns and sets out in the direction of the house, strike her with your sword and kill her.”

The ringleader went and stood beside her. The thieves, once within the house, lighted a light and opened the door of the room where the copper coins were kept. The female slave saw the thieves, went to the female lay disciple her mistress, and told her, “My lady, many thieves have entered your house and have opened the door of the room where the copper coins are kept.” The female lay disciple replied, “Let the thieves take all the copper coins they see. I am listening to my son as he preaches the Dhamma. Do not spoil the Dhamma for me. Go home.” So saying, she sent her back.

When the thieves had emptied the room where the copper coins were kept, they opened the door of the room where the silver coins were kept. The female slave went once more to her mistress and told her what had happened. The female lay disciple replied, “Let the thieves take whatever they will; do not spoil the Dhamma for me,” and sent her back again. When the thieves had emptied the room where the silver coins were kept, they opened the door of the room where the gold coins were kept. The female slave went once more to her mistress and told her what had happened. Then the female lay disciple addressed her and said, “Woman! you have come to me twice, and I have said to you, ‘Let the thieves take whatever they wish to; I am listening to my son as he preaches the Dhamma; do not bother me.’ But in spite of all I have said, you have paid no attention to my words; on the contrary, you come back here again and again just the same. If you come back here once more, I shall deal with you according to your deserts. Go back home again.” So saying, she sent her back.

When the leader of the thieves heard these words of the female lay disciple, he said to himself, “If we steal the property of such a woman as this, Indra’s thunderbolt will fall and break our heads.” So he went to the thieves and said, “Hurry and put back the wealth of the female lay disciple where it was before.” So the thieves filled again the room where the copper coins were kept with the copper coins, and the gold and silver rooms with the gold and silver coins. It is invariably true, we are told, that righteousness keeps whoever walks in righteousness.

Therefore said the Buddha,

Righteousness truly protects him who walks in righteousness;

Righteous living brings happiness.

Herein is the advantage of living righteously:

He who walks in righteousness will never go to a state of suffering.

The thieves went to the pavilion and listened to the Dhamma. As the night grew bright, the Venerable finished his recitation of the Dhamma and descended from the seat of the Dhamma. At that moment the leader of the thieves prostrated himself at the feet of the female lay disciple and said to her, “Pardon me, my lady” “Friend, what do you mean?” I took a dislike to you and stood beside you, intending to kill you.” “Very well, friend, I pardon you.” The rest of the thieves did the same. “Friends, I pardon you,” said the female lay disciple. Then said the thieves to the female lay disciple, “My lady, if you pardon us, obtain for us the privilege of entering the Sangha under your son.”

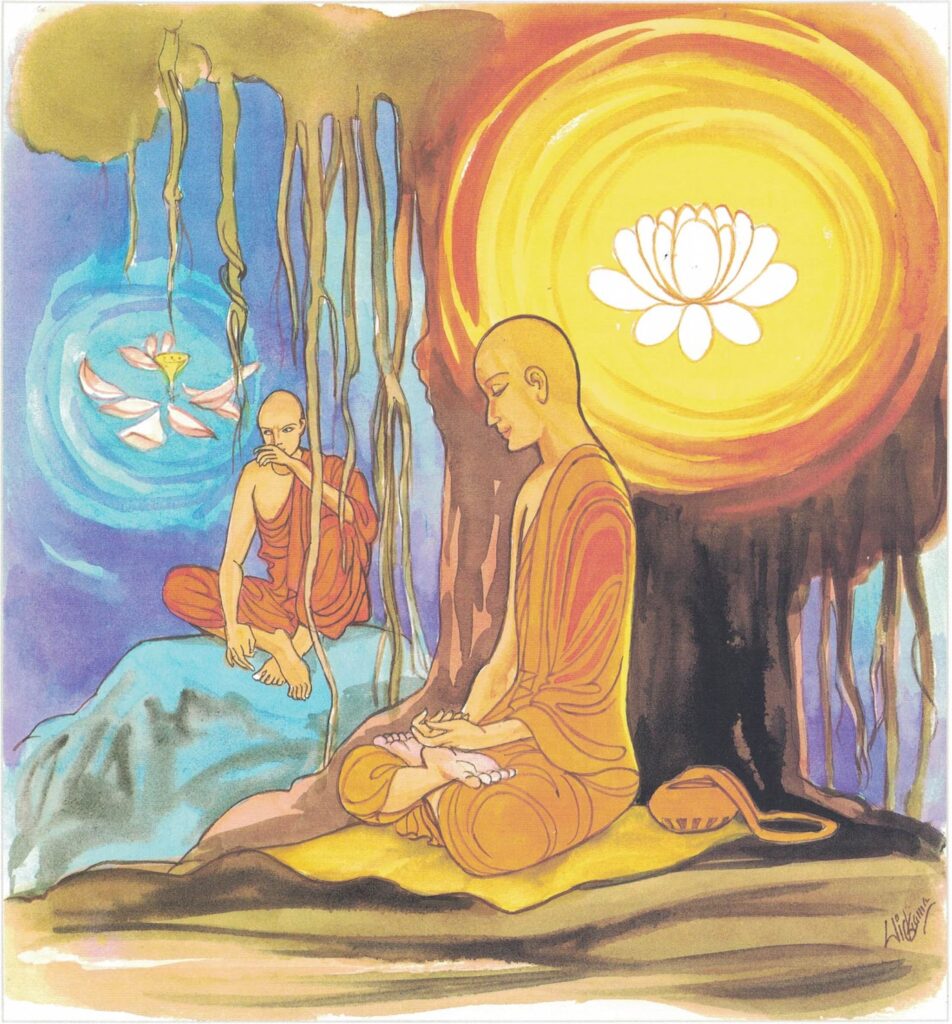

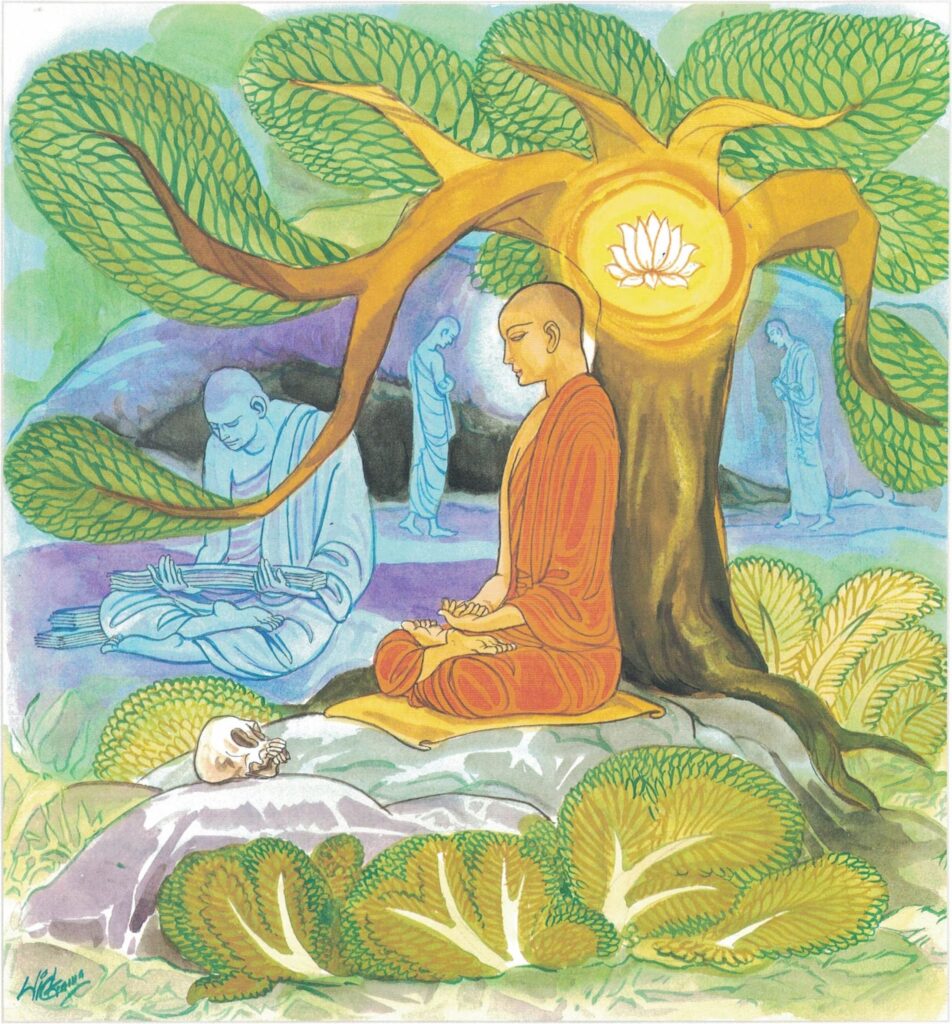

The female lay disciple saluted her son and said “Dear son, these thieves are so pleased with my good qualities and with your recitation of the Dhamma, that they desire to be admitted to the Sangha; admit them to the Sangha.” “Very well,” replied the Venerable. So he caused the skirts of the undergarments they wore to be cut off, had their garments dyed with red clay, admitted them to the Sangha, and established them in the Precepts. When they had made their full profession as members of the Sangha, he gave to each one of them a separate meditation topic. Then those nine hundred monks took the nine hundred meditation topics which they had severally received, climbed a certain mountain, and sitting each under the shadow of a separate tree, applied themselves to meditation.

The Buddha, even as he sat in the great monastery at Jetavana, a hundred and twenty leagues away, scrutinized those monks, chose a form of instruction suited to their dispositions, sent forth a radiant image of himself, and as though sitting face to face with them and talking to them, gave the stanzas.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 368)

yo bhikkhu mettāvihārī buddhasāsane pasanno

saṃkhārūpasamaṃ sukhaṃ santaṃ padaṃ adhigacche

yo bhikkhu: if a given monk; mettāvihārī: is full of lovingkindness; buddhasāsane: in the Teaching of the Buddha; pasanno [pasanna]: takes delight in; saṃkhārūpasamaṃ [saṃkhārūpasama]: pacifying the agitation of the existence; sukhaṃ [sukha]: bliss; santaṃ padaṃ [pada]: the tranquil state (Nibbāna); adhigacche: reaches

The monk who extends loving-kindness to all, takes delight in the Teaching of the Buddha, will attain the state of bliss, the happiness of Nibbāna, which denotes the pacifying of the agitation of existence.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 369)

bhikkhu imaṃ nāvaṃ siñca te sittā lahum essati

rāgañ ca dosañ ca chetvā tato nibbānam ehisi

bhikkhu: O monk; imaṃ nāvaṃ [nāva]: this boat; human life; siñca: empty; te: by you; sittā: emptied (this boat); lahum: being lightened and swift; essati: will reach Nibbāna; rāgañ ca: passion; dosañ ca: ill-will; chetvā: cut off, tato: then; nibbānam ehisi: reach Nibbāna.

O monk, your boat must be emptied of the water which, if accumulated, will sink it. Once the water is taken out and the boat is emptied, both lust and hate gone, it will swiftly reach the destination–Nibbāna.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 370)

pañca chinde jahe pañca ca uttari bhāvaye

pañca saṅgātigo bhikkhu oghatiṇṇo iti vuccati

pañca: the five (lower fetters); chinde: break off; pañca: the five (upper fetters); jahe: get rid of; pañca: the five (the wholesome faculties); uttari: especially; bhāvaye: cultivate; pañca saṅgātigo [saṅgātiga]: go beyond the five saṅga bonds; oghatiṇṇo iti: having crossed the stream; vuccati: is called

One should break away from the five lower fetters. One must get rid of the five higher fetters. One must cultivate the five faculties. One must go beyond five attachments. A monk who has achieved these is described as the one who has crossed the flood.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 371)

bhikkhu jhāya mā ca pamādo te cittaṃ kāmaguṇe mā bhamassu

pamatto lohagulaṃ ma gilī ḍayhamāno idaṃ dukkham kandi

bhikkhu: O monk; jhāya: meditate; mā ca pamādo [pamāda]: do not be indolent; te cittaṃ [citta]: your mind; kāmaguṇe: in five-fold sensual attractions; mā bhamassu: do not allow to loiter; pamatto [pamatta]: being indolent; lohagulaṃ [lohagula]: iron balls; mā gilī: do not swallow; ḍayhamāno [ḍayhamāna]: burning; idaṃ dukkham: oh, this is suffering; mā kandi: do not bewail

O monk, meditate and do not be indolent. Do not allow your mind to loiter among sensual pleasures. If you allow it, you will have iron balls forced down your throat in hell. You will bewail your fate crying, “This is suffering.” Do not allow that to happen.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 372)

apaññassa jhānam natthi ajhāyato paññā natthi

yamhi jhānañca paññā ca so ve nibbānasantike

apaññassa: to the unwise; jhānam natthi: (there is) no meditation; ajhāyato [ajhāyata]: to the one without meditation; paññā natthi: (there is) no wisdom; yamhi: in a person; jhānañca: meditation and; paññā ca: wisdom (are present); so: that person; ve: certainly; nibbānasantike: is close to Nibbāna

For one who lacks meditation there is no wisdom. Both of these, meditation and wisdom, are essential and one cannot be had without the other. If in a person, both meditation and wisdom are present, he is close to Nibbāna.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 373)

suññāgāraṃ paviṭṭhassa santacittassa dhammaṃ

sammā vipassato bhikkhuno amānusī ratī hoti

suññāgāraṃ [suññāgāra]: an empty house; paviṭṭhassa: to the one who has entered; santacittassa: to the person with a tranquil mind; dhammaṃ [dhamma]: the reality of things; sammā: good; vipassato [vipassata]: has an insight into; bhikkhuno [bhikkhuna]: the monk; amānusī: not known by ordinary mortals; ratī: an ecstasy; hoti: occurs

A monk who enters an empty house, whose mind is at peace, and who is capable of seeing the reality of things, experiences an ecstasy not known to ordinary mortals.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 374)

yato yato khandhānaṃ udayabbayaṃ sammasati

pīti pāmojjaṃ labhati taṃ vijānataṃ amataṃ

yato yato: as to when; khandhānaṃ [khandhāna]: aggregates; udayabbayaṃ [udayabbaya]: arise and decay;sammasati: contemplate wisely; pīti pāmojjaṃ [pāmojja]: joy and ecstasy; labhati: will accrue; taṃ: this; vijānataṃ [vijānata]: to those who know; amataṃ [amata]: is the deathless

When the meditator reflects upon the rise and the decay of the bodily aggregates he experiences a joy and ecstasy which is a foretaste of Nibbāna (amata) for those who know it.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 375)

idha paññassa bhikkhuno tatra ayaṃ ādi bhavati

indriyagutti santuṭṭhī pātimokkhe ca saṃvaro

ca suddhājīve atandite kalyāne mitte bhajassu

idha: in this Teaching; paññassa: to the wise meditators; tatra: in this contemplation of the rise and the decay; ayaṃ: thus; ādi bhavati: is the first step; indriyagutti: the guarding of the senses; santuṭṭhī: the three-fold contentment; pātimokkhe: in the code of discipline; saṃvaro ca: restraint; suddhājīve: those with purity of life; atandite: non-relaxed; kalyāne mitte: beneficial friends; bhajassu: associate

The joy experienced as a foretaste of Nibbāna, through the awareness of the rise and decay of the aggregates, is the first step for the wise meditator. Guarding the senses, even-mindedness, and discipline is the principal code of morality and the association with good friends who are unrelaxed in their effort and are pure in behaviour.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 376)

paṭisanthāravutiyassa ācārakusalo siyā

tato pāmojjabahulo dukkhassantaṃ

paṭisanthāravuti: courteous and pleasant behaviour; assa: one should be; ācārakusalo [ācārakusala]: skilful in the practice of religion; tato: due to that; pāmojjabahulo [pāmojjabahula]: being of high ecstasy; dukkhassa antaṃ karissati: you will end suffering

One should be courteous and of pleasant behaviour. One should be efficient in the conduct of the proper rites and rituals. Through these, one acquires a vast quantum of ecstasy, leading him to the ending of suffering.

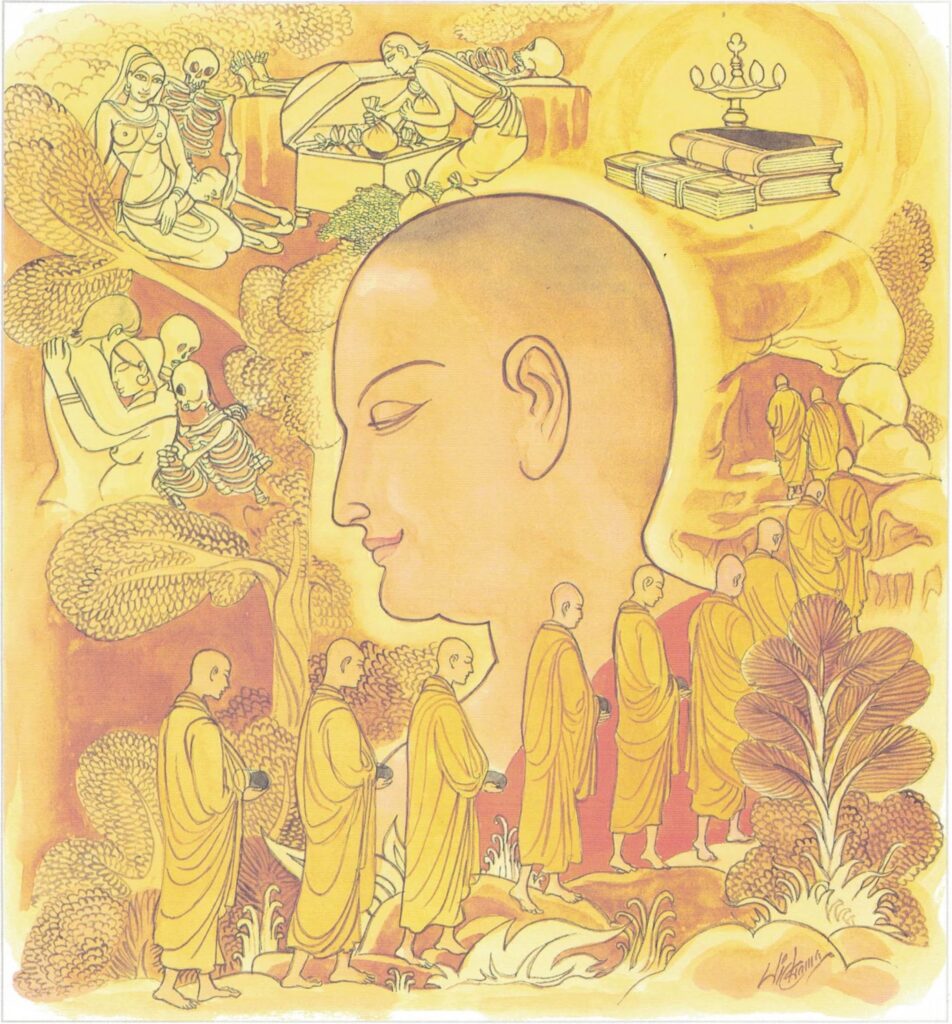

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 368-376)

mettāvihāri: In the Buddhist system considerable emphasis is placed on living with loving-kindness which is mettāvihāri.

Mettā, unbounded benevolence or friendliness, in itself emphasizes the positive nature of the self-sacrifice and devoted service of the aspirant, which is not confined to any one part or portion of existence, but is extended over the whole universe to include all beings, from the highest to the lowest, and from the greatest to the most minute form of life. Mettā, as exemplified in the Buddha and in his followers and expounded in the scriptures, is not an evanescent exhibition of emotion, but a sustained and habitual mental attitude of service, goodwill and friendship, which finds expression in deed, word and thought. There are numerous passages which can be collated to testify to the vital importance attached to this divine state in the Buddha’s Teaching.

The exercise of mettā, which, psychologically speaking, is a moral attribute, tends to the cultivation of the emotional sentiment of goodwill, rather than meditation itself. The disciple should, however, practice mettā in conjunction with other forms of meditation; for it is indispensable to one who seeks to purify his mind from anger and malice. Moreover, he will find that it is an essential support in the exercise of meditation, bringing immediate success and providing the means of protection from external hindrances with which he may have to contend.

In the Mahā Rāhulovāda Sutta we read of the Buddha advising his son, the Venerable Rāhula, to practice mettā on the ground that when it is cultivated, anger will disappear. In the Meghiya Sutta it is recommended to the Venerable Meghiya, who failed to achieve success in meditation at first, owing to the persistent arising of evil thoughts. He afterwards attained Arahatship, having expelled and excluded evil thoughts with the aid of the mettā he had developed.

Several methods of practicing mettā, as an independent form of meditation, are expounded in the canon in various connexions. In the treatment of this subject we should give more especial consideration to four methods that appear in the Sutta Piṭaka.

Of these four, the formula of the four-fold Brahmavihāra exercise which occurs most frequently in the Nīkāyas and which may be found in the Tevijja Sutta, deals principally with the method of ‘Disāpharana’. This consists in suffusing the whole world with the thought of mettā, expanded in all directions, and is associated with the jhāna stages.

We quote this formula here, together with its Pāli version, in order to show its distinctive character:

So mettāsahagatena cetasā ekaṃ disaṃ pharitvā viharati. Tathā dutiyaṃ, tathā catutthaṃ,

iti uddhaṃ adho, tiriyaṃ, sabbadhi, sabbattatāya, sabbāvantaṃ lokaṃ mettāsahagatena cetasā,

vipulena, mahaggatena, appamāṇena, averena, abyāpajjena pharitvā viharati.

Literally rendered thus:

He abides suffusing one quarter with (his) mind associated with friendliness.

Likewise, the second, the third, and the fourth; thus above, below, around, everywhere,

all as himself, the whole wide world, he abides suffusing with mind associated with friendliness,

abundant, grown great, immeasurable, free from enmity, free from ill-will.

This formula is discussed by Buddhaghosa Thera in his Visuddhimagga, where he distinguishes it as vikubbanā, a term which also occurs in connection with the iddhividha as vikubbanā-iddhi, where it means exercising psychic power of various forms. It implies the establishment of an immense sphere of benevolent thought, which is increased to the appaṇā or the jhāna stage. Hence, this formula indicates the habitual mental attitude of him who has attained to jhāna by the practice of mettā and we find it repeated with the substitution, one by one, of the other altruistic emotions of karuṇā, muditā and upekkhā.

Being the statement of the special mode of living to be adopted by the religious aspirant, this formula emphatically expresses his mental attitude in relation to the external world, especially in the jhāna state. Furthermore, it describes the outlook of the man who neither tortures himself nor inflicts injury upon others, but lives satisfied, tranquil, and cool, enjoying the happiness of serenity, himself a brahma (brahma bhūtena attanā). The special context of the formula corresponds to the Upāli Sutta where it is stated that those who have attained jhāna and psychic powers, but have not yet cultivated mettā, can destroy others by the mere disturbance of their minds through anger. It is said that in ancient days, the forests named Daṇḍaka, Kāliṅga, Mejjha, and Mātaṅga, became forests because of the anger of certain ancient sages (pubbakā isayo). But the disciple of the Buddha, as the formula says, abides suffusing the entire universe with his boundless love of mettā, free from all anger and malice.

The well-known Metta Sutta, or Karaṇīya Metta Sutta, sets forth the manner in which mettā should be practiced, both as means of self-protection and as a kammaṭṭhāna. It is there emphasized as an essential duty of the disciple who follows this system of religious training, seeking happiness and peace. This Sutta is one of the most important discourses selected for reciting during religious services and chanting at the Paritta ceremony, which is usually held on auspicious occasions, or in cases of affliction, epidemic, or individual sickness. It has a special importance for the disciple of meditation.

In the Yogāvacara’s Manual, we read that the Metta Sutta is to be recited in its Pāli form, as part of the invocation that should precede all exercises in meditation. The text of this Sutta is supposed to be so arranged that the words themselves have a certain sonorous power, to which importance is attached, and it is always chanted with a special intonation. But the main purpose of the Sutta is to expound the practice of mettā and to formulate a definite system of contemplative exercise. Moreover, it is a more special expansion of the method of suffusing mettā and corresponds to that shown in the formula of the Tevijja Sutta. Furthermore, it is in this Metta Sutta that mettā is compared to motherly love and named especially as a brahma-vihāra. The practice of this meditation alone leads to emancipation from re-birth, as emphasized in the saying, ‘So, shall he never come back again to re-birth.’

The other special application of mettā is found in the Khandha Paritta, where it is given as a safeguard against harm from snakes. This states that a certain monk of Sāvatthi died as the result of receiving a snakebite. A number of monks brought the news to the Buddha, who is reported to have said, “The monk had not practiced metta towards the four families of snakes. There are four families (kula) of snakes, namely, virūpakkha, erāpatha, chabyāputta and kaṇhāgotamaka. Had he practiced mettā towards these four kinds of snakes, he would not have died of snake-bite. I advise you, monks, to suffuse them with friendly thoughts (lit. mind–mettena cittena pharituṃ) for your own safeguard and protection.”

The actual method of suffusing is given here in verses, and is to be extended gradually, proceeding from the four families of snakes, thus:

May I have friendliness with the virūpakkhas,

May I have friendliness with the chabyāputtas,

With the erāpathas may I friendliness have,

With the kaṇhāgotamakas may I have friendliness.

The suffusion is then gradually extended, advancing in stages, and including different kinds of creatures; the footless, those that have two feet, the quadrupeds and the many-footed.

Thereafter, the disciple’s aspiration follows thus:

Let not the footless do me harm,

Nor those that have two feet;

Let not the quadrupeds do me harm,

Nor those with many feet.

He then continues, developing suffusion immeasurable:

Sabbe sattā sabbe pāṇā

Sabbe bhūtā ca kevalā—

Sabbe bhadrāni passantu;

Mā kañci pāpamāgamā.May all beings, all living things,

All that are born, and everyone,

May all see happiness,

And may no harm befall.

This stanza contains some of the actual words (such as sabbe sattā, sabbe pānā, sabbe bhūtā and so on) that occur in the formula for meditation, as given in later works.

Then follows the invocation:

Infinite is the virtue of the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Sangha;

Finite are creeping things, such as snakes, scorpions, centipedes,

spiders, house lizards, rats and mice.

I have done my warding, my protection.

Let all creatures turn away in peace.

Reverence to the Buddha, reverence to the seven fully Enlightened Ones.

This sutta has a very long and firmly established tradition. It occurs in the Khandha-Vatta Jātaka where the Bodhisatta advised his followers to observe this paritta (which is given in the same form) as a protection against serpents; for they were living in a spot in the Himālayan valley where such poisonous creatures were abundant. Observing this advice, the ascetics are said to have long lived unharmed, during the period that the Bodhisatta himself, who was practicing the brahma-vihāras, was bound to the brahma world. In relating this story of his past experience the Buddha advised the monks to observe the same paritta.

This meditational exercise is given in the Khuddaka-Vatta-Khandhaka of the Cullavagga as a rule of discipline and duty, and the special name Khandha Paritta is probably adopted from this connection.

Of these two parittas, the method expounded in the Metta Sutta corresponds to the practice as followed in the jhāna stage, as does also the formula found in the Tevijja Sutta; while the other seems to be a more primitive form of suffusion. Both, however, contain the anodhiso, the unlimited, and the odhiso, the limited forms of suffusion, which are explained in the Paṭisambhidā-magga, as will be seen below. Both methods, the unlimited and the limited, combine with that of disāpharaṇa, suffusing through all the directions or quarters given in the formula of the four-fold exercise. They may differ in the letter, but the spirit is the same everywhere.

A more widely extended suffusion of mettā, which corresponds to these formulae, is mentioned in the Mettākathā of the Patisambhidāmagga, where we find a detailed description of several methods, arranged in numerical order; they are combined severally with the Bodhipakkhiya principles of the five indriyas, the five balas, the seven bojjhaṅgas and the eight-fold path. First, the Mettānisaṃsa is quoted, a discourse that occurs in the Aṅguttara Nikāya and sets forth eleven advantages of Mettā-bhāvanā.

Then the following methods of suffusing mettā are enumerated: there are three methods, namely:

- Anodhiso Pharanā–suffusing without a limit;

- odhiso Pharanā–suffusing with a limit, and

- Disā Pharanā–suffusing through the directions or quarters.

(1) The Anodhiso method is sub-divided into five, each section forming a separate meditation formula. They are:

- sabbe sattā–all beings;

- sabbe pāṇā–all living things;

- sabbe bhūtā–all creatures;

- Sabbe puggalā–all persons or individuals and

- sabbe attabhāva pariyāpannā– all that have come to individual existence.

Each of these five is linked with the four copulas of aspiration:

- averā hontu–let [them] be free from enmity;

- abyāpajjā hontu–let [them] be free from ill-will;

- anighā hontu–let [them] be rid of ill and

- sukhī attānaṃ pariharantu–let [them] keep themselves happy.

In the case of the abovementioned the full formula should be repeated, thus: Let all beings be free from enmity; be free from ill-will; be rid of ill or suffering; and let them keep themselves happy.

Likewise: Let all living things, all creatures, all individuals, and all that are existing (each successively), be free from enmity, hatred, ill, and let them keep themselves happy.

In following this method the aspirant includes all beings in his thoughts of loving-kindness and pervades them with it, without limitation–touching all without localization as the commentary says. Hence, it is anodhiso pharanā, suffusing without a limit or boundary.

(2) There are seven forms of odhiso pharanā, or the limited method:

- sabbe itthiyo–all females;

- Sabbe Purisā–all males;

- Sabbe ariyā–all worthy ones, or those who have attained perfection;

- sabbe anariyā–all unworthy ones, or those who are imperfect;

- sabbe devā–all gods;

- sabbe manussā–all human beings;

- sabbe vinipātikā–all those in unhappy states.

Each of these should be linked with the four aspirations and repeated separately or collectively during the period of meditation.

In employing this method the aspirant suffuses mettā, while dividing beings into groups according to their nature and condition. The meditation is, therefore, called odhiso pharanā or suffusing within a limit or portion.

(3) There are ten modes of suffusing mettā through the quarters and the intermediate quarters, starting from the East. They comprise the eight points of the compass: the four cardinal points, the four intermediate points, and above and below.

The formulas are:

Let all beings in the East be free from enmity,

hatred, ill, and let them keep themselves happy.

In like manner:

Let all beings in the West, the North, the South, the North-east,

the South-west, the North-west, the South-East,

above and below, be free from enmity, etc.

In these three methods of suffusing mettā there are twenty-two (five, seven and ten) formulas; and each, according to the commentary, refers to the mettā that leads to the appaṇā or jhāna state.

Of the five anodhiso pharanās,

‘Let all beings be free from enmity’ is one Appaṇā;

‘Be free from ill-will’ is another;

‘Be rid of ill’ is another;

‘Let them keep themselves happy’ is the fourth.

Thus, in the method of unlimited suffusion, there are twenty appaṇās, that is, four in each of the five formulas. In the same way, four appaṇās in each of the seven formulas give a total of twenty-eight belonging to the method of limited suffusion.

The five (i to v) formulas of the odhiso method have also been combined with the ten directions, thus:

Let all beings in the East be free from enmity… and so forth. In this way, there are two hundred appaṇās, twenty in each quarter.

In like manner, the seven (i to vii) formulas, being combined with the ten directions as:

Let all women in the East… and so on give a total of two hundred and eighty appaṇās, that is, twenty-eight in each quarter.

There are, thus, four hundred and eighty appaṇās. In all, there are five hundred and twenty-eight appaṇās (twenty, twenty-eight, two hundred and two hundred and eighty), mentioned in the Patisambhidā-magga.

The commentary states that the other three vihāras, karuṇā, muditā and upekkhā, are also employed with the same method of suffusing; and the disciple who practises them by means of any one of these appaṇā states, enjoys the eleven blessings spoken of in the following Mettānisaṃsa Sutta passage:

Monks, from the practice of mettā-cetovimutti or mind-release through friendliness, cultivated, increased, made a vehicle (yānikatā), made a basis (vatthukatā), persisted in, made familiar, well set forth, eleven blessings are to be expected. What are the eleven?

Happy he sleeps; happy he awakes; he dreams no bad dreams; he is dear to men; dear to non-human beings; Devās guard him; fire, poison, or sword come not near him; quickly his mind becomes concentrated; his complexion becomes clear; he dies with his mind free from confusion; if he realizes no further attainment, he goes to the brāhma-world.