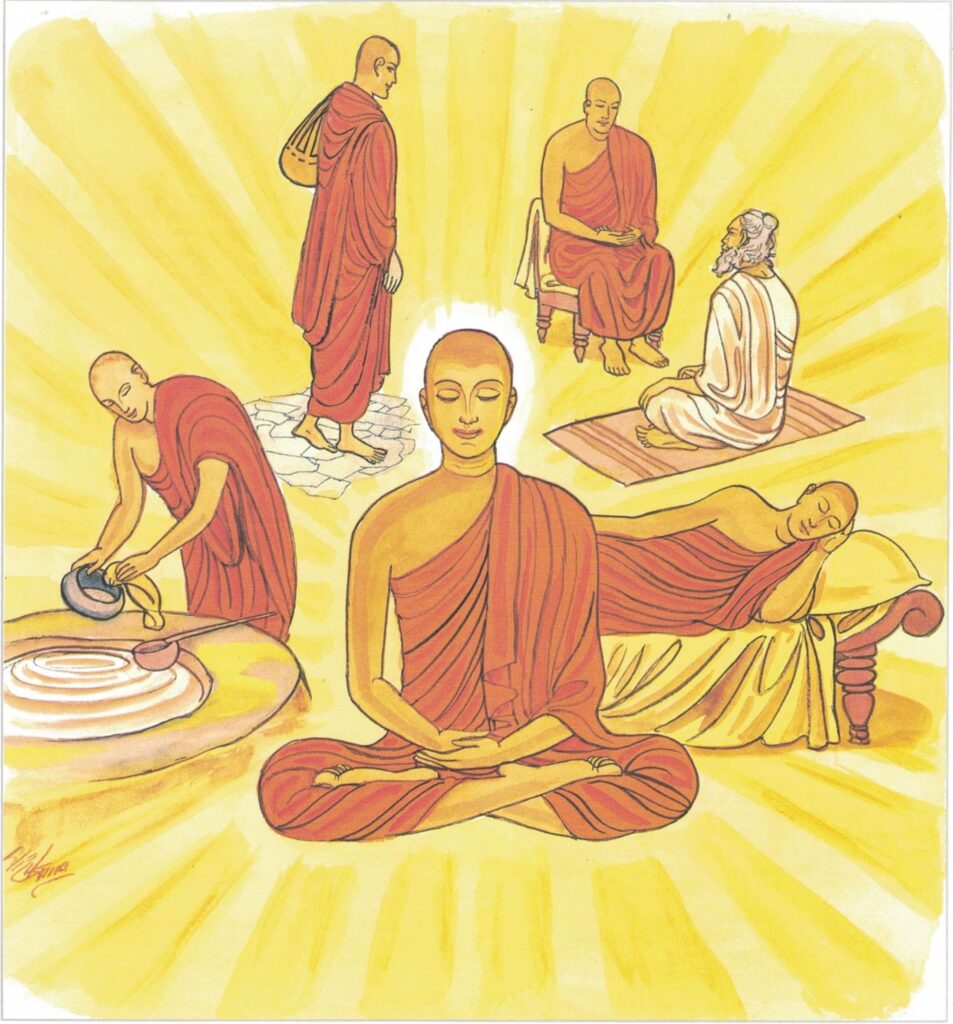

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 362:

hatthasaññato pādasaññato vācāya saññato saññatuttamo |

ajjhattarato samāhito eko santusito tamā’hu bhikkhuṃ || 362 ||

362. With hands controlled and feet controlled, in speech as well as head controlled, delighting in inward collectedness alone, content, a bhikkhu’s called.

The Story of a Monk Who Killed a Swan (Haṃsa)

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse with reference to a monk who killed a swan.

The story goes that two residents of Sāvatthi retired from the world, were admitted to full membership in the Sangha, and becoming fast friends, usually went about together. One day they went to the Aciravatī River, and after bathing, stood on the bank basking themselves in the rays of the sun, engaged in pleasant conversation. At that moment two geese came flying through the air. Thereupon one of the young monks, picking up a pebble, said, “I am going to hit one of these young geese in the eye.” “You can’t do it,” said the other.

“You just wait,” said the first; “I will hit the eye on this side of him, and then I will hit the eye on the other side of him.” “You can’t do that, either,” said the second. “Well then, see for yourself,” said the first, and taking a second pebble, threw it after the goose. The goose, hearing the stone whiz through the air, turned his head and looked back. Then the second monk picked up a round stone and threw it in such a way that it hit the eye on the far side and came out of the eye on the near side. The goose gave a cry of pain, and tumbling through the air, fell at the feet of the two monks.

Some monks who stood near saw the occurrence and said to the monk who had killed the goose. “Brother, after retiring from the world in the religion of the Buddha, you have done a most unbecoming thing in taking the life of a living creature.” And taking the two monks with them, they arraigned them before the Buddha. The Buddha asked the monk who had killed the goose, “Is the charge true that you have taken the life of a living creature?” “Yes, Venerable,” replied the monk, “it is true.”

The Buddha asked, “Monk, how comes it that after retiring from the world in such a religion as mine, leading to salvation as it does, you have done such a thing as this? Wise men of old, before the Buddha appeared in the world, though they lived amid the cares of the household life, entertained scruples about matters of the most trifling character. But you, although you retired from the world in the religion of the Buddha, have felt no scruples at all?”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 362)

hattha saññato pāda saññato vācāya saññato saññatuttamo

ajjhattharato samāhito eko santusito taṃ bhikkhuṃ āhu

hattha saññato [saññata]: if someone is restrained in hand; pāda saññato [saññata]: if someone is restrained in foot; vācāya saññato [saññata]: restrained in words; saññatuttamo [saññatuttama]: restrained in body; ajjhattharato [ajjhattharata]: if he is focussed on his meditation object; samāhito [samāhita]: if his mind is tranquil; eko: if he is in solitude; santusito [santusita]: if he is contented; taṃ: him; bhikkhuṃ [bhikkhu]: the monk; āhu: is called

He who controls his hand, controls his foot, controls his speech, and has complete control of himself; who finds delight in insight development practice and is calm; who stays alone and is contented, they call him a monk.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 362)

samāhito: a mind that is tranquil: a mind that has attained samādhi–tranquility through total concentration.

The word samādhi is best rendered by concentration. Moreover, it is one of the original terms used by the Buddha himself, for it occurs in His first Sermon. It is used in the sense of sammā-samādhi, right concentration. Samādhi from the root saṃādhā, to put together, to concentrate, refers to a certain state of mind. In a technical sense it signifies both the state of mind and the method designed to induce that state.

In the dialogue between the sister Dhammadinnā and the devotee Visākhā, Samādhi is discussed both as a state of mind and a method of mental training. Visākhā asked, “What is Samādhi?” The sister replied, “Samādhi is cittassa ekaggatā (literally, one-pointedness of mind).” “What induces it?” “The four applications of mindfulness (Satipaṭṭhāna), induce it.” “What are its requisites?” “The four supreme efforts (sammappadhāna) are its requisites.” “What is the culture (Bhāvanā) of it?” “Cultivation and increase of those self-same principles–mindfulness and supreme effort, are the culture of it.”

In this discussion samādhi, as a mental state, is defined as cittassa ekaggatā, and this appears to be the first definition of it in the Suttas. In the Abhidhamma this definition is repeated and elaborated with a number of words that are very similar, indeed, almost synonymous.