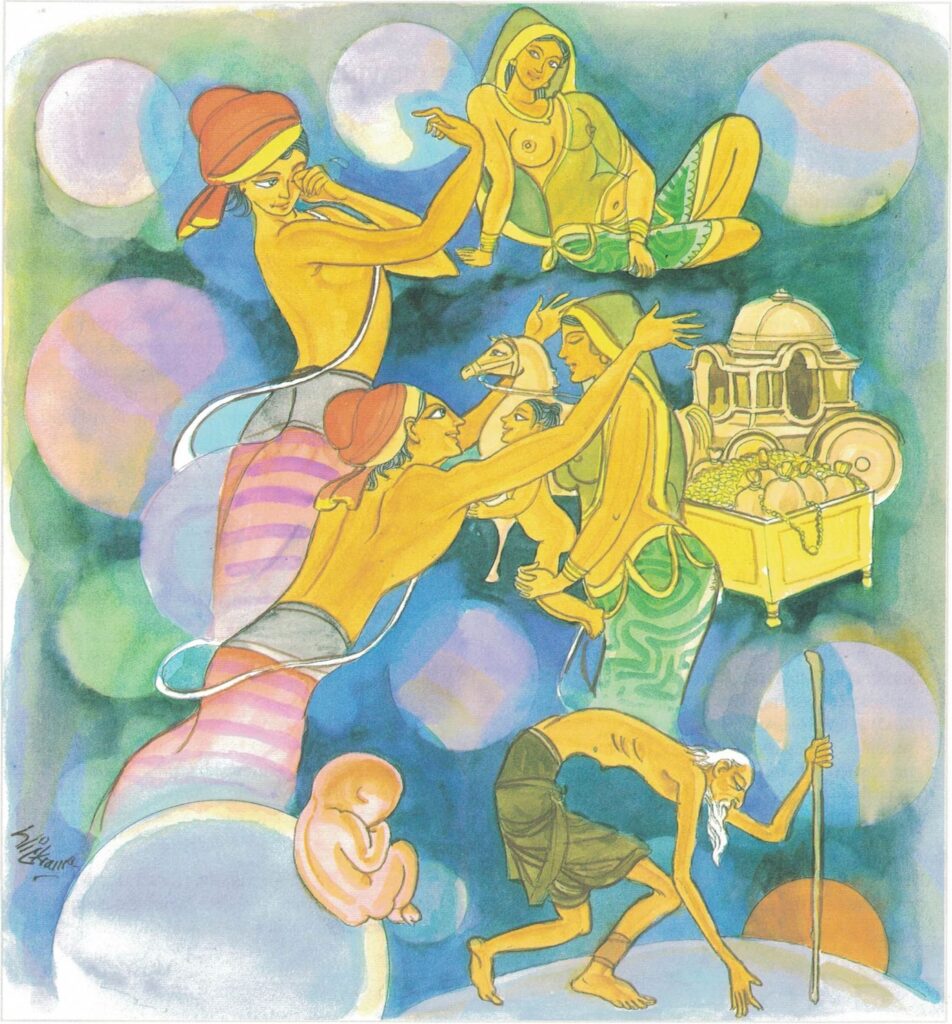

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 338-343:

yathā’pi mūle anupaddave daḷhe chinno’pi rukkho punar’eva rūhati |

evam’pi taṇhānusaye anūhate nibbatti dukkham idaṃ punappunaṃ || 338 ||

yassa chattiṃsati sotā manāpassavanā bhūsā |

vāhā vahanti duddiṭṭhiṃ saṅkappā rāganissitā || 339 ||

savanti sabbadhi sotā latā ubbhijja tiṭṭhati |

tañ ca disvā lataṃ jātaṃ mūlaṃ paññāya chindatha || 340 ||

saritāni sinehitāni ca somanassāni bhavanti jantuno |

te sātasitā sukhesino te ve jātijarūpagā narā || 341 ||

tasiṇāya purakkhatā pajā parisappanti saso’va bādhito |

saṃyojanasaṅgasattā dukkhamupenti punappunaṃ cirāya || 342 ||

tasiṇāya purakkhatā pajā parisappanti saso’va bādhito |

tasmā tasiṇaṃ vinodaya bhikkhu ākaṅkhī virāgamattano || 343 ||

338. As tree though felled shoots up again if its roots are safe and firm so this dukkha grows again while latent craving’s unremoved.

339. For whom the six and thirty streams so forceful flow to seemings sweet floods of thought that spring from lust sweep off such wrong viewholders.

340. Everywhere these streams are swirling, up-bursting creepers rooted firm. Seeing the craving-creeper there with wisdom cut its root!

341. To beings there are pleasures streaming sticky with desire, steeped in comfort, happiness seeking, such ones do come to birth, decay.

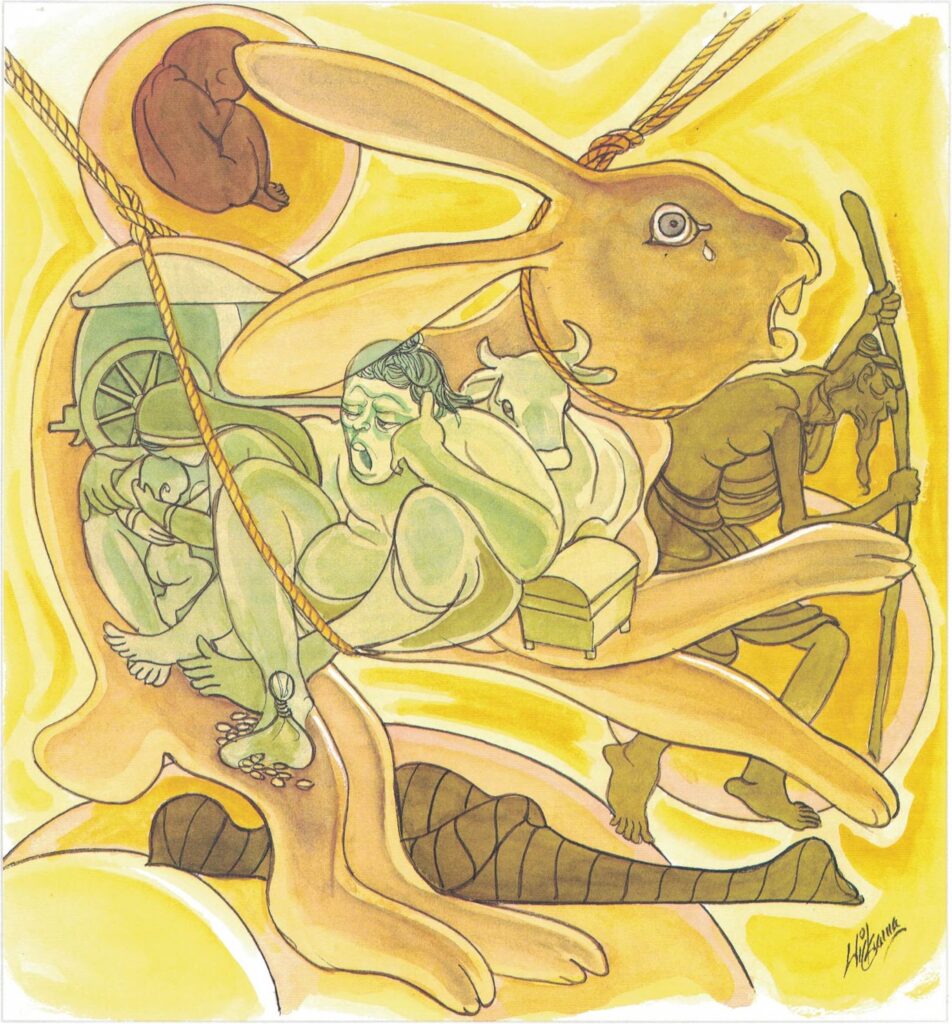

342. Who follow craving are assailed, they tremble as the hare ensnared, held fast by fetters and by bonds so long they come to dukkha again.

343. Who follow craving are assailed, they tremble as the hare ensnared, so let a bhikkhu craving quell bhikkhu whose aim is passionlessness.

The Young Sow

The story goes that one day, as the Buddha was entering Rājagaha for alms, seeing a young sow, he smiled. Venerable Ānanda, seeing the circle of light which proceeded from his teeth and came forth from his open mouth, asked the Buddha his reason for smiling, saying, “Venerable, what is the cause of your smile?” The Buddha said to him, “Ānanda, just look at that young sow!” “I see her, Venerable.”

“In the dispensation of exalted Kakusandha she was a hen that lived in the neighbourhood of a certain hall of assembly. She used to listen to a certain monk who lived the life of contemplation, as he repeated a formula of meditation leading to insight. Merely from hearing the sound of those sacred words, when she passed out of that state of existence, she was reborn in the royal household as a princess named Ubbarī.

“One day she went to the privy and saw a heap of maggots. Then and there, by gazing upon the maggots, she formed the conception of maggots and entered into the first trance. After remaining in that state of existence during the term of life allotted to her, she passed out of that state of existence and was reborn in the world of brahmā. Passing from that state of existence, buffeted by rebirth, she has now been reborn as a young sow. It was because I knew these circumstances that I smiled.”

As the monks led by Venerable Ānanda listened to the Buddha they were deeply moved. The Buddha, having stirred their emotions, proclaimed the folly of craving, and even as he stood there in the middle of the street, pronounced the following Stanzas:

338. As a tree, though it be cut down, grows up again if its rootbe sound and firm, So also, if the inclination to craving be not destroyed, this suffering springs up again and again in this world.

339. He that is in the tow of the six and thirty powerful currentsrunning unto pleasure, such a man, misguided, the waves of desires inclining unto lust sweep away.

340. The currents run in all directions; the creeper buds andshoots; when you see the creeper grown, be wise and cut the root.

341. Flowing and unctuous are a creature’s joys; men devotethemselves to pleasure and seek after happiness; therefore do they undergo birth and decay.

342. Pursued by craving, men dart hither and thither like ahunted hare; held fast by fetters and bonds, they undergo suffering repeatedly and long.

343. Pursued by craving, men dart hither and thither like ahunted hare. Therefore a monk should banish craving, desiring for himself freedom from lust.

The young sow, after passing out of that state of existence, was reborn in Suvaṇṇabhūmi in the royal household. Passing from that state of existence, she was reborn at Benāres; passing from that state of existence, she was reborn at Suppāraka Port in the household of a dealer in horses, then at Kāvīra Port in the household of a mariner. Passing from that state of existence, she was reborn in Anurādhapura in the household of a nobleman of high rank. Passing from that state of existence, she was reborn in the South country in the village of Bhokkanta as the daughter of a householder named Sumanā, being named Sumanā after her father.

When this village was deserted by its inhabitants, her father went to the kingdom of Dīghavāpi, and took up his residence in the village of Mahāmuni. Arriving here on some errand or other Lakuṇṭaka Atimbara, minister of King Duṭṭhagāmanī, met her, married her with great pomp, and took her with him to live in the village of Mahāpuṇṇa. One day Venerable Anula, whose residence was the Mahā Vihāra of Koṭipabbata, stopped at the door of her house as he was going his round for alms, and seeing her, spoke thus to the monks, “Venerables, what a wonderful thing that a young sow should become the wife of Lakuṇṭaka Atimbara, prime minister of the king!”

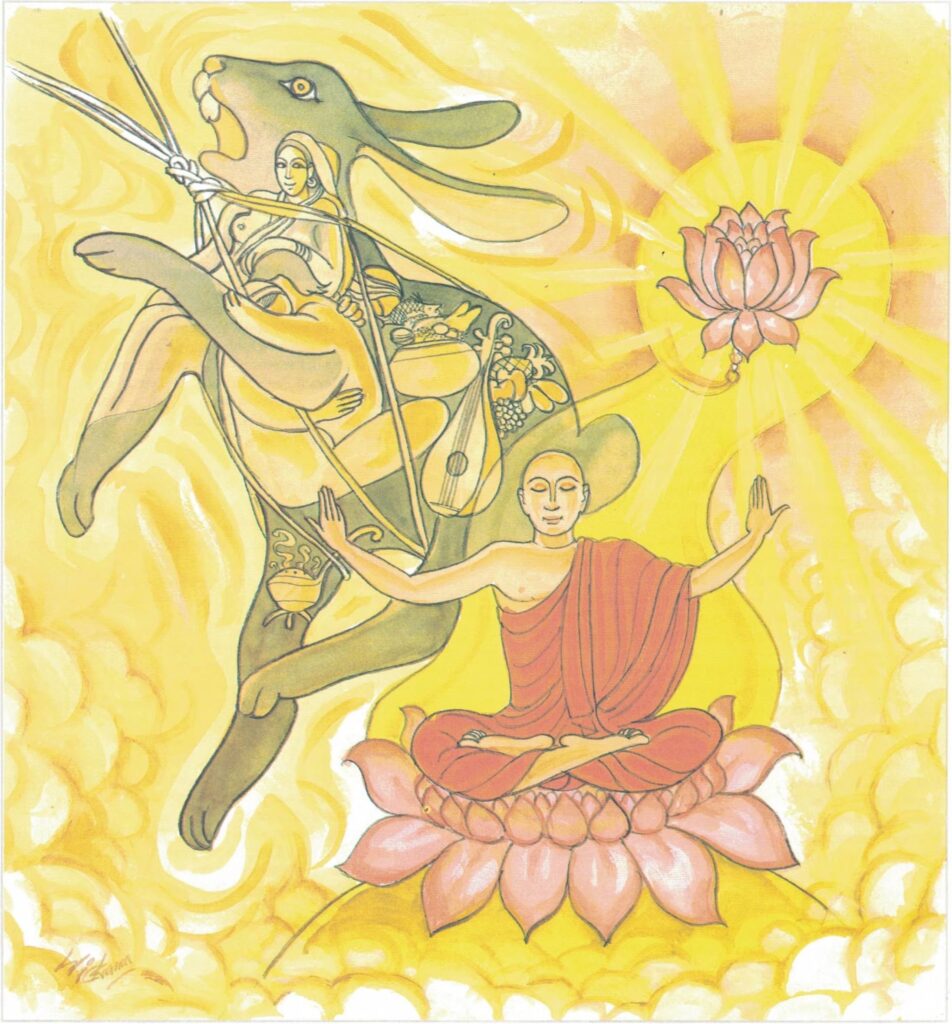

When she heard his words, she uncovered her past states of existence, and she received the power of remembering previous births. Instantly she was deeply moved, and obtaining permission of her husband, retired from the world with great pomp and became a nun of the order of Pañcabālaka nuns. After listening to the recitation of the Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Suttanta in Tissa Mahā Vihāra, she was established in the fruit of conversion. Subsequently, after the crushing of the Damiḷas, she returned to the village of Bhokkanta, where her mother and father lived, and took up her residence there. After listening to the Āsīvisopama Sutta in Kallaka Mahā Vihāra, she attained arahatship. On the day before she passed into Nibbāna, questioned by the monks and nuns, she related this whole story to the community of nuns from the beginning to the end; likewise in the midst of the assembled community of monks, associating herself with the Venerable Mahā Tissa, a reciter of the Dhammapada and a resident of Maṇḍalārāma, she related the story as follows:

“In former times I fell from human estate and was reborn as a hen. In this state of existence my head was cut off by a hawk. I was reborn at Rājagaha, retired from the world, and became a wandering nun, and was reborn in the stage of the first trance. Passing from that state of existence, I was reborn in the household of a treasurer. In but a short time I passed from that state of existence and was reborn as a young sow. Passing from that state of existence, I was reborn in Suvaṇṇabhūmi; passing from that state of existence, I was reborn at Vārāṇasī passing from that state of existence, I was reborn at Suppāraka Port; passing from that state of existence, I was reborn at Kāvīra Port; passing from that state of existence, I was reborn at Anurādhapura; passing from that state of existence, I was reborn in Bhokkanta village. Having thus passed through thirteen states of existence, for better or for worse, in my present state of existence I became dissatisfied, retired from the world, became a nun, and attained arahatship. Every one of you, work out your salvation with heedfulness.” With these words did she stir the four classes of disciples with emotion; and having so done, passed into Nibbāna.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 338)

yathā api mūle anupaddave daḷhe chinno api rukkho puna eva rūhati

evam api tanhānusaye anūhate idaṃ dukkhaṃ punappunaṃ nibbattatī

yathā api: when; mūle: the root; anupaddave: unharmed; daḷhe: (and) strong; chinno api: though cut down; rukkho [rukkha]: the tree; puna eva: once again; rūhati: grows up; evam api: in the same way; tanhānusaye: the hidden traces of craving; na ūhate: when not totally uprooted; idaṃ dukkhaṃ [dukkha]: this suffering; punappunaṃ [punappuna]: again and again; nibbattatī: will grow

Even when a tree has been cut down, it will grow up again if its roots are strong and unharmed. Similarly, when traces of craving remain, the suffering is likely to arise again and again.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 339)

yassa chattiṃsatī sotā manāpassavanā bhusā

duddiṭṭhiṃ rāganissitā saṅkappā vāhā vahanti

yassa: in whom; chattiṃsatī sotā: thirty-six streams; manāpassavanā: attractive to the mind; bhusā: (craving) are powerful; duddiṭṭhiṃ [duddiṭṭhi]: unwise; rāganissitā: mixed with sensuality; saṅkappā: thoughts and feelings; vāhā: (are) very powerful; vahanti: (this) leads them (to hell)

If in a person the thirty-six streams flow strongly towards pleasurable thoughts, that person of depraved views will be carried away on those currents of craving.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 340)

sotā savanti sabbadhi latā ubbhijja tiṭṭhati jātaṃ

taṃ lataṃ ca disvā paññāya mūlaṃ chindatha

sotā: the streams (of craving); savanti: flow; sabbadhī: everywhere; latā: the creeper; ubbhijja: has sprung up; tiṭṭhati: (and) stays; jātaṃ [jāta]: that sprung up; latā: creeper (of craving);disvā: having seen; paññāya: with wisdom; mūlaṃ [mūla]: the root;chindatha: cut down

The streams of craving flow towards objects everywhere. As a result, a creeper springs up and flourishes. The wise, when they see this creeper, should cut its root with wisdom.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 341)

saritāni sinehitāni somanassāni jantuno bhavanti

te sātasitā sukhesino te narā ve jātijarūpagā

saritāni: flowing towards objects; sinehitāni: soaked with craving; somanassāni: pleasures; jantuno [jantuna]: people; bhavanti: have; te: they; sātasitā: seek pleasure; sukhesino [sukhesina]: pursue happiness; te narā: such persons; ve: certainly; jātijarūpagā: go to birth and decay

Craving arises in people like flowing streams. These flow towards pleasure and sensual satisfaction. Such people who are bent on pleasures will experience repeated cycles of birth and decay.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 342)

tasiṇāya purakkhatā pajā bādhito saso eva parisappanti

saññojanasaṅgasattā cirāya punappunaṃ dukkham upenti

tasiṇāya: by craving; purakkhatā: surrounded; pajā: masses; bādhito [bādhita]: entrapped; saso eva: like a hare; parisappanti: tremble;saññojanasaṅgasattā: shackled by fetters; cirāya: for a long time; punappunaṃ [punappuna]: again and again; dukkham: to suffering; upenti: come

Surrounded by craving the masses tremble like a hare caught in a trap. Shackled by ten fetters and seven saṅgas, men and women suffer again and again over a long period of time.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 343)

tasiṇāya purakkhatā pajā parisappanti saso iva bādhito

tasmā tasiṇaṃ vinodaye bhikkhu ākaṅkhī tasiṇaṃ vinodaye

tasiṇāya: by craving; purakkhatā: surrounded; pajā: masses; parisappanti: tremble; saso iva: like a hare; bādhito [bādhita]: entrapped; tasmā: therefore; attano [attana]: to one’s own self, vinodaye: should shun; bhikkhu: the ascetic; ākaṅkhī: desiring; tasiṇaṃ [tasiṇa]: craving

Surrounded by craving, the masses tremble like a hare caught in a trap. Therefore, a monk desiring to attain detachment–Nibbāna–should shun craving.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 338-343)

anupaddave daḷhe: The comparison is with a tree. Even if the tree is pruned, and if the roots are unharmed and strong, it will grow up again.

punareva rūhati: If the roots are strong and unharmed, the tree will sprout again, although the trunk has been cut.

chattiṃ satī sotā: thirty-six streams of craving. The eighteen bases (of craving) dependent on the internal and on the external (āyatana): craving itself arising in one’s stream of consciousness with regard to the six objects, pertaining to the past, future, and present, is called the ‘eighteen bases of craving.’ Thirty-six streams: Namely, the eighteen bases of craving that exist having the internal āyatanas, such as eyes, etc., as their sphere, and the eighteen bases of craving that exist having the external āyatanas, such as form, etc., as their sphere. Here, the thirty-six-fold craving exists in three dimensions, i.e., craving for sensuality, craving for existence, craving for the cessation of existence, having as its sphere the six internal āyatanas (i.e., 3 x 6 = 18), namely, eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, mind, and the six external āyatanas (i.e., 3 x 6 = 18), namely, form, sound, smell, taste, touch, dharmas, is called the (18 + 18) thirty-six streams.

rāga nissitā: thoughts that are mixed with thoughts of passion and sensuality.

savanti: the streams of craving are flowing. Throughout the stanza, this idea is taken up.

latā ubbhijja tiṭṭhati: watered by the streams of craving, a creeper springs up, which is the creeper of craving.

mūlaṃ paññāya chindatha: cut off the root with wisdom.

saritāni: the idea of stream is being continued. Saritāni implies flowing towards objects.

sātasitā: those who are gripped by craving. They take up delightful and pleasurable experiences.

bādhito: entrapped; caught in a snare. The hare is generally a timid creature. Its fear will be far more pronounced when entrapped.

saññojanasaṅga: ten fetters (saṃyojanas) seven bonds (saṅga) bind the masses to saṃsāra.

Ten saṃyojanas, or defilements, are:

- holding to the opinion of enduring substantiality (sakkāyadiṭṭhi),

- (skeptical) doubt (vicikicchā),

- clinging to precept and practices (sīlabbataparāmāsa),

- passion for sensual desires, (kāmarāga),

- ill-will (vyāpāda),

- passion for the fine-material (realm) (rūparāga),

- passion for the formless (realm) (arūparāga),

- self-estimation (māna),

- agitation (uddhaccaṃ), and

- ignorance (avijjā).

They are of two modes: (i) pertaining to the upper part and (ii) pertaining to the lower part. They are called fetters because they bind beings in saṃsāra in the sense that they cause rebirth there again and again. The five, beginning with holding to the opinion of enduring substantiality, and so on, are called those pertaining to the lower part, because they are the cause for birth in the eleven realms of sensuality that are called lower (realms), and five, beginning with passion for the finematerial (realm), and so on, are called those pertaining to the upper part because they are the cause for birth in the fine-material realm and the formless realm, which are called upper. There is no liberation from saṃsāra for beings until these bonds of saṃsāra, which are of these two, are rooted out.

Seven-fold attachments, (saṅgayo) are: craving, views, self-estimation, anger, ignorance, defilements and misconduct. Some say (they are) the seven latent dispositions (anusaya), i.e., passion, hatred, self-estimation, views, (speculative) doubt, passion for existence, and ignorance. The activity of clinging with regard to the saṃskāras, having taken the five skandhās as a sentient being, a person, etc., is in the mode of either craving, views, etc., or passion, hatred, etc. Hence, they are called attachments.

ākaṅkhī virāgam: one who is desirous of attaining the state of detachment–Nibbāna.

Rebirth: This story is replete with several layers of rebirth. Some of the rebirths referred to took place even after the days of the Buddha. In some instances the rebirths take place in Sri Lanka. The concepts of the origin of life and of rebirth have been interpreted in various ways by scholars. Here is one point of view:

Rebirth, which Buddhists do not regard as a mere theory but as a fact verifiable by evidence, forms a fundamental tenet of Buddhism, though its goal, Nibbāna, is attainable in this life itself. The Bodhisatta Ideal and the correlative doctrine of freedom to attain utter perfection are based on this doctrine of rebirth.

Documents record that this belief in rebirth is viewed as transmigration or reincarnation, in many great poems by Shelley, Tennyson and Wordsworth, and writings of many ordinary people in the East as well as in the West.

The Buddhist doctrine of rebirth should be differentiated from the theory of transmigration and reincarnation of other systems, because Buddhism denies the existence of a transmigrating permanent soul, created by a god, or emanating from a paramātma (divine essence).

It is kamma that conditions rebirth. Past kamma conditions the present birth; and present kamma, in combination with past Kamma, conditions the future. The present is the offspring of the past, and becomes, in turn, the parent of the future.

The reality of the present needs no proof as it is self-evident. That of the past is based on memory and report, and that of the future on forethought and inference.

If we postulate a past, a present and a future life, then we are at once faced with the problem–What is the ultimate origin of life?

One school, in attempting to solve the problem, postulates a first cause, whether as a cosmic force or as an almighty being. Another school denies a first cause, for in common experience, the cause ever becomes the effect and the effect becomes the cause. In a circle of cause and effect a first cause is inconceivable. According to the former, life has had a beginning; according to the latter, it is beginningless. In the opinion of some the conception of a first cause is like saying a triangle is round.

One might argue that life must have had a beginning in the infinite past and that beginning is the first cause, the creator.

In that case there is no reason why some may not make the same demand about a postulated creator.

With respect to this alleged first cause men have held widely different views. In interpreting this first cause, many names have been used.

Hindu traces the origin of life to a mystical paramātma from which emanate all ātmās or souls that transmigrate from existence to existence until they are finally reabsorbed in Paramātma. One might question whether these reabsorbed ātmās have further transmigration.

“Whoever,” as Schopenhaeur says, “regards himself as having come out of nothing must also think that he will again become nothing; for that an eternity has passed before he was, and then a second eternity had begun, through which he will never cease to be, is a monstrous thought.

“Moreover, if birth is the absolute beginning, then death must be the absolute end; and the assumption that man is made out of nothing, leads necessarily to the assumption that death is his absolute end.” “According to the theological principles,” argues Spencer Lewis, “man is created arbitrarily and without his desire, and at the moment of creation is either blessed or unfortunate, noble or depraved, from the first step in the process of his physical creation to the moment of his last breath, regardless of his individual desires, hopes, ambitions, struggles or devoted prayers. Such is theological fatalism.

In “Despair”, a poem of his old age, Lord Tennyson, referring to theist theology, said:

“I make peace and create evil.

What I should call on that infinite love that has served us so well? Infinite cruelty rather that made everlasting hell.

Made us, foreknew us, foredoomed us, and does what he will with his own.

Better our dead brute mother who never has heard us groan.”

“The doctrine that all men are sinners and have the essential sin of Adam is a challenge to justice, mercy, love and omnipotent fairness”. Huxley said: “If we are to assume that anybody has designedly set this wonderful universe going, it is perfectly clear to me that he is no more entirely benevolent and just, in any intelligible sense of the words, than that he is malevolent and unjust”.

According to Einstein: “If this being is omnipotent, then every occurrence, including every human action, every human thought, and every human feeling and aspiration is also his work; how is it possible to think of holding men responsible for their deeds and thoughts before such an almighty being?

In giving out punishments and rewards, He would to a certain extent be passing judgment on himself. How can this be combined with the goodness and righteousness ascribed to him?”

According to Charles Bradlaugh: “The existence of evil is a terrible stumbling block to the theist. Pain, misery, crime, poverty confront the advocate of eternal goodness, and challenge with unanswerable potency his declaration of Deity as all-good, all-wise, and all-powerful.” Commenting on human suffering and creator, Prof. J.B.S. Haldane writes: “Either suffering is needed to perfect human character, or God is not Almighty. The former theory is disproved by the fact that some people who have suffered very little but have been fortunate in their ancestry and education have very fine characters. The objection to the second is that it is only in connection with the universe as a whole that there is any intellectual gap to be filled by the postulation of a deity. And a creator could presumably create whatever he or it wanted.”

Dogmatic writers of old authoritatively declared that the creator created man after his own image. Some modern thinkers state, on the contrary, that man created his creator after his own image. With the growth of civilization man’s conception of God grows more and more refined. There is at present a tendency to substitute this personal creator by an impersonal god. Voltaire states that the conception of a creator is the noblest creation of man.

It is however impossible to conceive of such an omnipotent, omnipresent being, an epitome of everything that is good–either in or outside the universe.

Modern science endeavours to tackle the problem with its limited systematized knowledge. According to the scientific standpoint, we are the direct products of the sperm and ovum cells provided by our parents. But science does not give a satisfactory explanation with regard to the development of the mind, which is infinitely more important than the machinery of man’s material body. Scientists, while asserting “Omne vivum ex vivo” “all life from life” maintain that mind and life evolved from the lifeless.

Now from the scientific standpoint we are absolutely parent-born. Thus our lives are necessarily preceded by those of our parents and so on. In this way life is preceded by life until one goes back to the first protoplasm or colloid. As regards the origin of this first protoplasm or colloid, however, scientists plead ignorance.

What is the attitude of Buddhism with regard to the origin of life? At the outset it should be stated that the Buddha does not attempt to solve all the ethical and philosophical problems that perplex mankind. Nor does He deal with speculations and theories that tend neither to edification nor to enlightenment. Nor does He demand blind faith from His adherents. He is chiefly concerned with one practical and specific problem–that of suffering and its destruction; all side issues are completely ignored.

“It is as if a person were pierced by an arrow thickly smeared with poison, and his friends and relatives were to procure a surgeon, and then he were to say. ‘I will not lead the holy life under the Buddha until He elucidated to me whether the world is eternal or not eternal, whether the world is finite or infinite…’ That person would die before these questions had ever been elucidated by the Buddha.

“If it be the belief that the world is eternal, will there be the observance of the holy life? In such a case–No! If it be the belief that the world is not eternal, will there be the observance of the holy life? In that case also–No! But, whether the belief be that the world is eternal or that it is not eternal, there is birth, there is old age, there is death, the extinction of which in this life itself I make known.”

“Mālunkyaputta, I have not revealed whether the world is eternal or not eternal, whether the world is finite or infinite. Why have I not revealed these? Because these are not profitable, do not concern the bases of holiness, are not conducive to aversion, to passionlessness, to cessation, to tranquility, to intuitive wisdom, to enlightenment or to Nibbāna. Therefore I have not revealed these.” According to Buddhism, we are born from the matrix of action (kammayoni). Parents merely provide us with a material layer. Therefore being precedes being. At the moment of conception, it is kamma that conditions the initial consciousness that vitalizes the fœtus. It is this invisible kammic energy, generated from the past birth, that produces mental phenomena and the phenomena of life in an already extant physical phenomena, to complete the trio that constitutes man.

Dealing with the conception of beings, the Buddha states: “Where three are found in combination, there a germ of life is planted. If mother and father come together, but it is not the mother’s fertile period, and the being-to-be-born (gandhabba) is not present, then no germ of life is planted. if mother and father come together, and it is the mother’s fertile period, but the being-to-be-born is not present then again no germ of life is planted. If mother and father come together and it is the mother’s fertile period, and the being-to-be-born is present, then by the conjunction of these three, a germ of life is there planted.”

Here gandhabba (=gantabba) does not mean ‘a class of devas, said to preside over the process of conception’, but refers to a suitable being ready to be born in that particular womb. This term is used only in this particular connection, and must not be mistaken for a permanent soul. For a being to be born here, somewhere this being must die. The birth of a being, which strictly means the arising of the aggregates (khandhānaṃ pātubhāvo), or psycho-physical phenomena in this present life, corresponds to the death of a being in a past life; just as, in conventional terms, the rising of the sun in one place means the setting of the same sun in another place. This enigmatic statement may be better understood by imagining life as a wave and not as a straight line. Birth and death are only two phases of the same process. Birth precedes death, and death, on the other hand, precedes birth. This constant succession of birth and death in connection with each individual life-flux constitutes what is technically known as saṃsāra–recurrent wandering.

What is the ultimate origin of life? The Buddha positively declares: Without cognizable beginnings this saṃsāra, the earliest point of beings who, obstructed by ignorance and fettered by craving, wander and fare on, is not to be perceived. This life-stream flows ad infinitum, as long as it is fed with the muddy waters of ignorance and craving. When these two are completely cut off, then only does the life-stream cease to flow, rebirth ends, as in the case of Buddhas and arahats. A first beginning of this life-stream cannot be determined, as a stage cannot be perceived when this life force was not fraught with ignorance and craving. It should be understood that the Buddha has here referred merely to the beginning of the life-stream of living beings.

Rebirth: But the four mental aggregates, viz, consciousness and the three other groups of mental factors forming nāma or the unit of consciousness, go on uninterruptedly arising and disappearing as before, but not in the same setting, because that setting is no more. They have to find immediately a fresh physical base as it were, with which to function–a fresh material layer appropriate and suitable for all the aggregates to function in harmony. The kammic law of affinity does this work, and immediately a resetting of the aggregates takes place and we call this rebirth.

But it must be understood that in accordance with Buddhist belief, there is no transmigration of a soul or any substance from one body to another. According to Buddhist philosophy what really happens, is that the last javana or active thought process of the dying man releases certain forces which vary in accordance with the purity of the five javana thought moments in that series. (Five, instead of the normal seven javana thought-moments). These forces are called kamma vega or kammic energy which attracts itself to a material layer produced by parents in the mother’s womb. The material aggregates in this germinal compound must possess such characteristics as are suitable for the reception of that particular type of kammic energy. Attraction in this manner of various types of physical aggregated produced by parents occurs through the operation of death and gives a favourable rebirth to the dying man. An unwholesome thought gives an unfavourable rebirth.

In brief, the combination of the five aggregates is called birth. Existence of these aggregates as a bundle is called life. Dissolution of these things is called death. And recombination of these aggregates is called rebirth. However, it is not easy for an ordinary man to understand how these so-called aggregates recombine. Proper understanding of the nature of elements, mental and kammic energies and cooperation of cosmic energies is important in this respect. To some, this simple and natural occurrence–death, means the mingling of the five elements with the same five elements and thereafter nothing remains. To some, it means transmigration of the soul from one body to another; and to others, it means indefinite suspension of the soul; in other words, waiting for the day of judgment. To Buddhists, death is nothing but the temporary end of this temporary phenomenon. It is not the complete annihilation of this so-called being.