Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 32:

appamādarato bhikkhu pamāde bhaya dassivā |

abhabbo parihāṇāya nibbāṇasseva santike || 32 ||

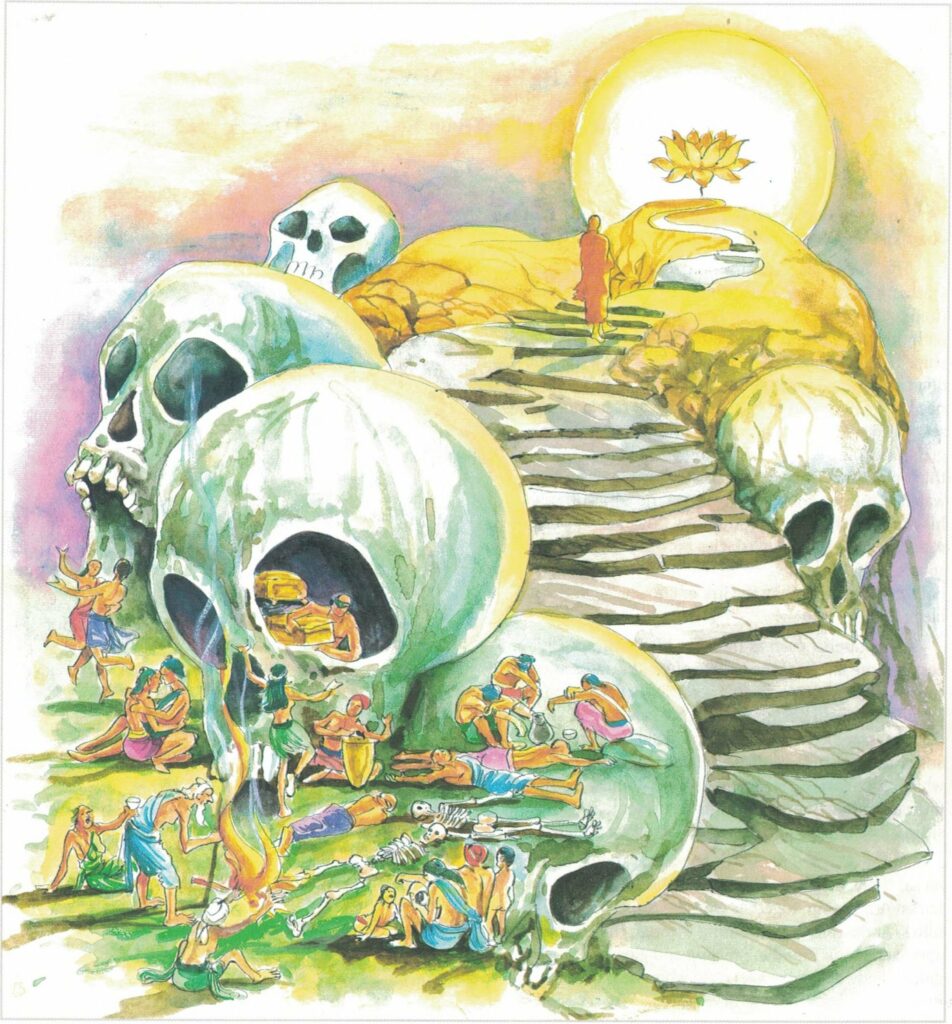

32. The bhikkhu liking heedfulness, seeing fear in heedlessness, never will he fall away, near is he to Nibbāna.

The Story of Monk Nigāma Vāsi Tissa

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to the monk Nigāma Vāsi Tissa.

A youth of high station, born and reared in a certain market town not far from Sāvatthi, retired from the world and became a monk in the religion of the Buddha. On making his full profession, he became known as Tissa of the Market-town, or Nigāma Tissa. He acquired the reputation of being frugal, content, pure, resolute. He always made his rounds for alms in the village where his relatives resided. Although, in the neighbouring city of Sāvatthi, Anāthapiṇḍika and other disciples were bestowing abundant offerings and Pasenadi Kosala was bestowing gifts beyond compare, he never went to Sāvatthi.

One day the monks began to talk about him and said to the teacher, “This monk Nigāma Tissa, busy and active, lives in intimate association with his kinsfolk. Although Anāthapiṇḍika and other disciples are bestowing abundant offerings and Pasenadi Kosala is bestowing gifts beyond compare, he never comes to Sāvatthi.” The Buddha had Nigāma Tissa summoned and asked him, “Monk, is the report true that you are doing thus and so?” “Venerable,” replied Tissa, “It is not true that I live in intimate association with my relatives. I receive from these folk only so much food as I can eat. But after receiving so much food, whether coarse or fine, as is necessary to support me, I do not return to the monastery, thinking, ‘Why seek food?’ I do not live in intimate association with my relatives, venerable.” The Buddha, knowing the disposition of the monk, applauded him, saying, ‘Well done, well done, monk!” and then addressed him as follows, “It is not at all strange, monk, that after obtaining such a teacher as I, you should be frugal. For frugality is my disposition and my habit.” And in response to a request of the monks he related the following.

Once upon a time several thousand parrots lived in a certain grove of fig-trees in the Himālayan country on the bank of the Ganges. One of them, the king-parrot, when the fruits of the tree in which he lived had withered away, ate whatever he found remaining, whether shoot or leaf or bark, drank water from the Ganges, and being very happy and contented, remained where he was. In fact he was so very happy and contented that the abode of Sakka began to quake.

Sakka, observing how happy and contented the parrot was, visited him and turned the whole forest into a green and flourishing place. The Buddha pointed out that even in the past birth he was contented and happy and that such a monk will never slip back from the vicinity of Nibbāna.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 32)

appamādarato pamāde bhayadassi vā bhikkhu

abhabbo parihānāya nibbānassa santike eva

appamādarato [appamādarata]: taking delight in mindfulness; pamāde: in slothfulness; bhayadassi vā: seeing fear; bhikkhu: the monk; abhabbo parihānāya: unable to slip back; nibbānassa: of Nibbāna; santike eva: is indeed in the vicinity.

The monk as the seeker after truth, sees fear in lack of mindfulness. He will certainly not fall back from any spiritual heights he has already reached. He is invariably in the proximity of Nibbāna.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 32)

Nibbāna: referring to Nibbāna the Buddha says, “O monks, there is the unborn, ungrown, and unconditioned. Were there not the unborn, ungrown, and unconditioned, there would be no escape for the born, grown, and conditioned, so there is escape for the born, grown, and conditioned.” “Here the four elements of solidity, fluidity, heat and motion have no place; the notions of length and breadth, the subtle and the gross, good and evil, name and form are altogether destroyed;neither this world nor the other, nor coming, going or standing, neither death nor birth, nor sense-objects are to be found.” Because Nibbāna is thus expressed in negative terms, there are many who have got a wrong notion that it is negative, and expresses self-annihilation. Nibbāna is definitely no annihilation of self, because there is no self to annihilate. If at all, it is the annihilation of the very process of being, of the conditional continuous in saṃsāra, with the illusion or delusion of permanency and identity, with a staggering ego of I and mine.

abhabbo parihānāya: not liable to suffer fall. A monk who is so (mindful) is not liable to fall either from the contemplative processes of samatha and vipassanā or from the path and Fruits–that is, does not fall away from what has been reached, and will attain what has not yet been reached.