Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 281:

vācānurakkhī manasā susaṃvuto kāyena ca akusalaṃ na kayirā |

ete tayo kammapathe visodhaye ārādhaye maggaṃ isippaveditaṃ || 281 ||

281. In speech ever watchful with mind well-restrained never with the body do unwholesomeness. So should one purify these three kamma-paths winning to the Way made known by the Seers.

The Story of a Pig Spirit

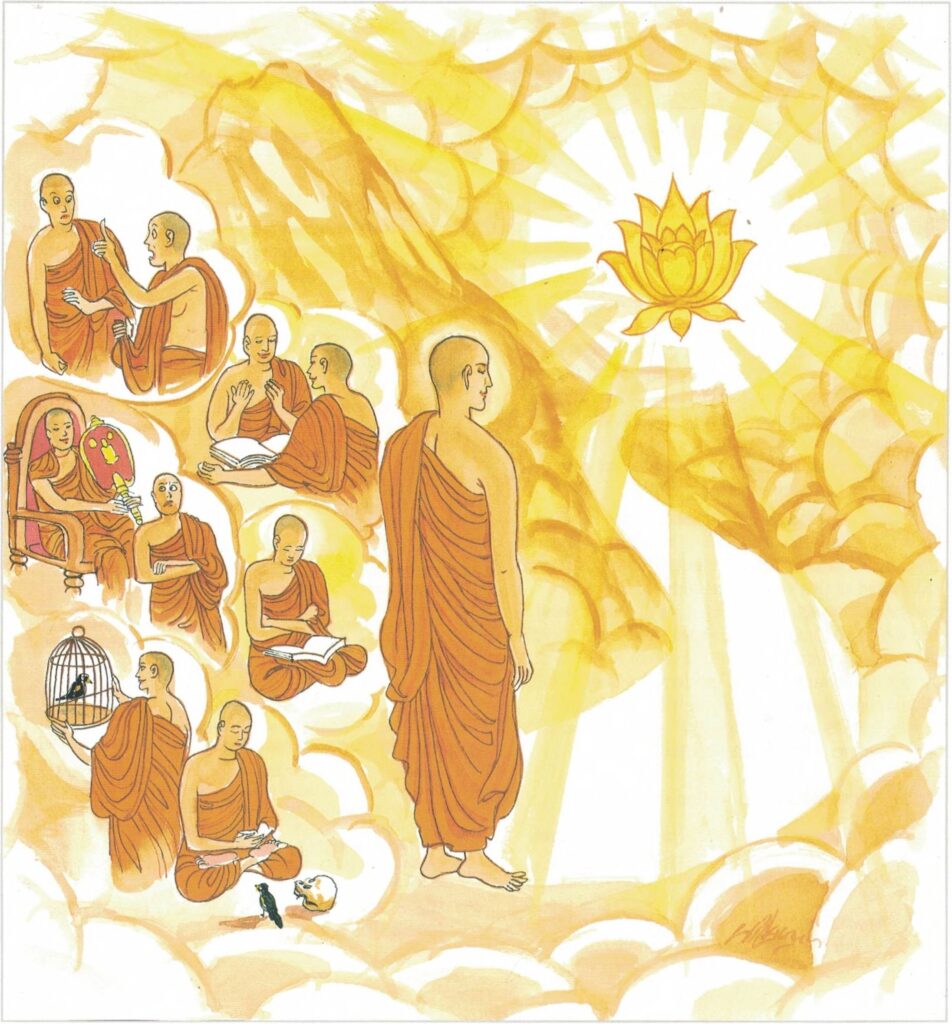

While residing at the Veluvana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse with reference to a pig spirit.

Once Venerable Mahā Moggallāna was coming down the Gijjhakūṭa hill with Venerable Lakkhana when he saw a miserable, ever-hungry spirit (peta), with the head of a pig and the body of a human being. On seeing the peta, Venerable Mahā Moggallāna smiled but did not say anything. Back at the monastery, Venerable Mahā Moggallāna, in the presence of the Buddha, talked about this peta with its mouth swarming with maggots. The Buddha also said that he himself had seen that very peta soon after his attainment of Buddhahood, but that he did not say anything about it because people might not believe him and thus they would be doing wrong to him. Then the Buddha proceeded to relate the story about this peta.

During the time of Kassapa Buddha, this particular peta was a monk who often expounded the Dhamma. On one occasion, he came to a monastery where two monks were staying together. After staying with those two for some time, he found that he was doing quite well because people liked his expositions. Then it occurred to him that it would be even better if he could make the other two monks leave the place and have the monastery all to himself. Thus, he tried to set one against the other. The two monks quarrelled and left the monastery in different directions. On account of this evil deed, that monk was reborn in Avīci Niraya and he was serving out the remaining part of his term of suffering as a swine-peta with its mouth swarming with maggots. Then the Buddha exhorted, “A monk should be calm and well-restrained in thought, word and deed.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 281)

vācānurakkhī manasā susaṃvuto, kāyena ca

akusalaṃ na kayirā ete tayo kammapathe

visodhaye isippaveditaṃ maggaṃ ārādhaye

vācānurakkhī: well guarded in speech; manasā: in mind; susaṃvuto [susaṃvuta]: well restrained; kāyena ca: even by body; akusalaṃ [akusala]: evil actions; na kayirā: are not done; ete tayo kammapathe: (keeps) these three doors of action; visodhaye: cleansed; isippaveditaṃ [isippavedita]: realized by the sages; maggaṃ [magga]: the noble eight-fold path; ārādhaye: (he) will attain

If one is well-guarded in speech, well-restrained in mind and if one refrains from committing sins physically, he will certainly attain the noble eight-fold path realized by the sages.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 281)

Tayo kammapathe: the three doors of kamma (action)–speech, mind and body. Views regarding kamma tend to be controversial. Though we are neither absolutely the servants nor the masters of our kamma, it is evident from counteractive and supportive factors that the fruition of kamma is influenced to some extent by external circumstances, surroundings, personality, individual striving, and the like. It is this doctrine of kamma that gives consolation, hope, reliance, and moral courage to a Buddhist. When the unexpected happens, difficulties, failures, and misfortunes confront him, the Buddhist realizes that he is reaping what he has sown, and is wiping off a past debt. Instead of resigning himself, leaving everything to kamma, he makes a strenuous effort to pull out the weeds and sow useful seeds in their place, for the future is in his hands. He who believes in kamma, does not condemn even the most corrupt, for they have their chance to reform themselves at any moment. Though bound to suffer in woeful states, they have the hope of attaining eternal peace. By their deeds they create their own hells, and by their own deeds they can also create their own heavens. A Buddhist who is fully convinced of the law of kamma does not pray to another to be saved but confidently relies on himself for his emancipation. Instead of making any self-surrender, or propitiating any supernatural agency, he would rely on his own will-power and work incessantly for the weal and happiness of all.

The belief in kamma, “validates his effort and kindles his enthusiasm” because it teaches individual responsibility. To an ordinary Buddhist kamma serves as a deterrent, while to an intellectual it serves as an incentive to do good. This law of kamma explains the problem of suffering, the mystery of the so-called fate and predestination of some religions, and above all the inequality of mankind. We are the architects of our own fate. We are our own creators. We are our own destroyers. We build our own heavens. We build our own hells. What we think, speak and do, become our own. It is these thoughts, words, and deeds that assume the name of kamma and pass from life to life exalting and degrading us in the course of our wanderings in saṃsāra.

The Buddha said:

Man’s merits and the sins he here hath wrought:

That is the thing he owns, that takes he hence.

That dogs his steps, like shadows in pursuit.

Hence let him make good store for life elsewhere.

Sure platform in some other future world,

Rewards of virtue on good beings wait.