Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 28:

pamādaṃ appamādena yadā nudati paṇḍito |

paññāpāsādamāruyha asoko sokiniṃ pajaṃ |

pabbataṭṭho’va bhummaṭṭhe dhīro bāle avekkhati || 28 ||

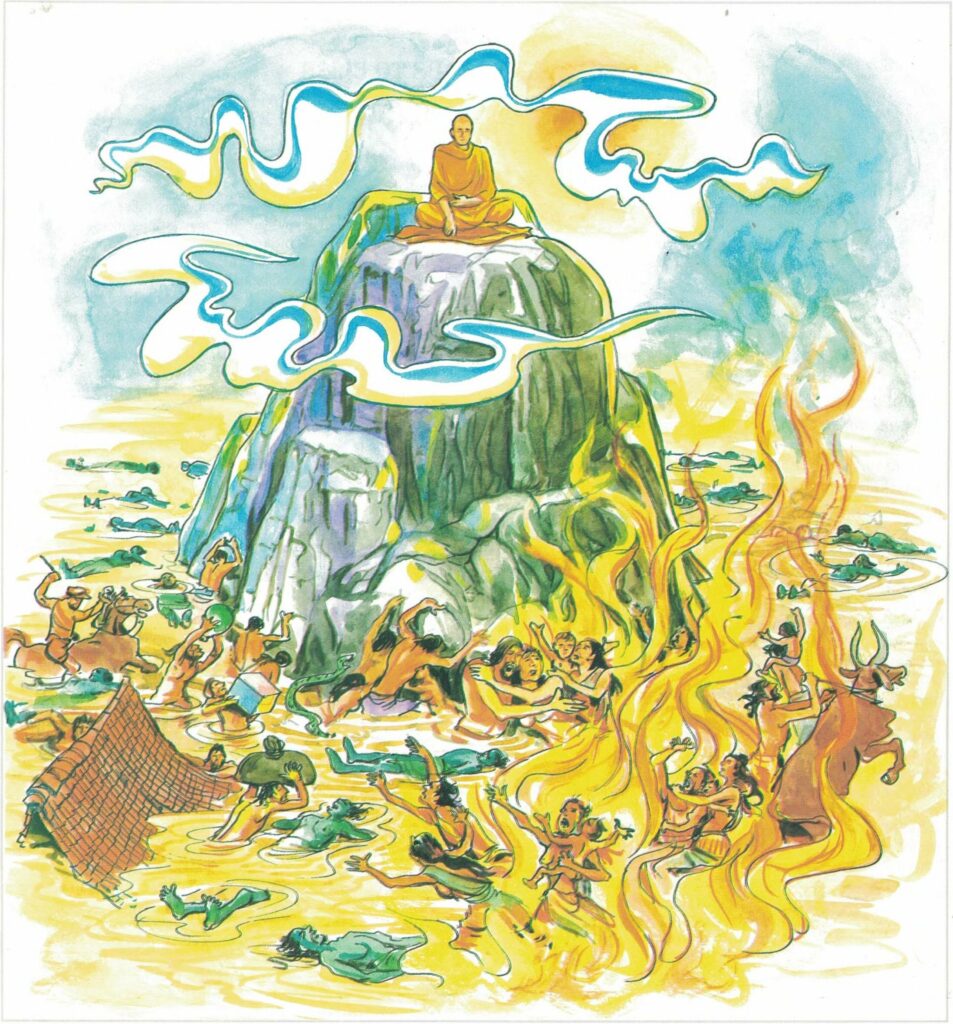

28. When one who’s wise does drive away heedlessness by heedfulness, having ascended wisdom’s tower steadfast, one surveys the fools, griefless, views the grieving folk, as mountaineer does those below.

The Story of Monk Mahākassapa

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to Monk Mahākassapa.

On a certain day, while the Buddha was in residence at the Pipphali Cave, he made his round of Rājagaha for alms and after he had returned from his round for alms and had eaten his breakfast, he sat down and using psychic powers surveyed with Supernormal Vision all living beings, both heedless and heedful, in the water, on the earth, in the mountains, and elsewhere, both coming into existence and passing out of existence.

The Buddha, seated at Jetavana, exercised supernormal vision and pondered within himself, “With what is my son Kassapa occupied today?” Straightaway he became aware of the following, “He is contemplating the rising and falling of living beings.” And he said, “Knowledge of the rising and falling of living beings cannot be fully understood by you. Living beings pass from one existence to another and obtain a new conception in a mother’s womb without the knowledge of mother or father, and this knowledge cannot be fully understood. To know them is beyond your range, Kassapa, for your range is very slight. It comes within the range of the Buddhas alone, to know and to see in their totality, the rising and falling of living beings.” So saying, he sent forth a radiant image of himself, as it were, sitting down face to face with Kassapa.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 28)

paṇḍito yadā appamādena pamādaṃ nudati dhīro

paññāpāsādaṃ āruyha asoko sokiniṃ pajaṃ

pabbataṭṭho bhummaṭṭhe iva bāle avekkhati

paṇḍito [paṇḍita]: the wise individual; yadā: when; appa mādena: through mindfulness; pamādaṃ [pamāda]: sloth; nudati: dispels; dhīro [dhīra]: the wise person; paññāpāsādaṃ [paññāpāsāda]: the tower of wisdom; āruyha: ascending; asoko [asoka]: unsorrowing; sokiniṃ [sokini]: the sorrowing; pajaṃ [paja]: masses; avekkhati: surveys; pabbataṭṭho iva: like a man on top of a mountain; bhummaṭṭhe: those on the ground; bāle: the ignorant: avekkhati: surveys.

The wise person is always mindful. Through this alertness he discards the ways of the slothful. The wise person ascends the tower of wisdom. Once he has attained that height he is capable of surveying the sorrowing masses with sorrowless eyes. Detached and dispassionate he sees these masses like a person atop a mountain peak, surveying the ground below.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 28)

sokiniṃ pajaṃ: this establishes a characteristic of the ordinary masses–the worldly men and women. They are all described as ‘sorrowing’. Sorrow, suffering, is an inescapable condition of ordinary life. Only the most advanced men of wisdom can rise above this condition of life. Sorrow, or suffering, has been described by the Buddha as a universal truth. Birth is suffering, decay is suffering, disease is suffering, death is suffering, to be united with the unpleasant is suffering, to be separated from the pleasant is suffering, not to get what one desires is suffering. In brief, the five aggregates of attachment are suffering. The Buddha does not deny happiness in life when he says there is suffering. On the contrary he admits different forms of happiness, both material and spiritual, for laymen as well as for monks. In the Buddha’s Teachings, there is a list of happinesses, such as the happiness of family life and the happiness of the life of a recluse, the happiness of sense pleasures and the happiness of renunciation, the happiness of attachment and the happiness of detachment, physical happiness and mental happiness etc. But all these are included in suffering. Even the very pure spiritual states of trance attained by the practice of higher meditation are included in suffering.

The conception of suffering may be viewed from three aspects: (i) suffering as ordinary suffering, (ii) suffering as produced by change and (iii) suffering as conditioned states. All kinds of suffering in life like birth, old age, sickness, death, association with unpleasant persons and conditions, separation from beloved ones and pleasant conditions, not getting what one desires, grief, lamentation, distress–all such forms of physical and mental suffering, which are universally accepted as suffering or pain, are included in suffering as ordinary suffering. A happy feeling, a happy condition in life, is not permanent, not everlasting. It changes sooner or later. When it changes, it produces pain, suffering, unhappiness. This vicissitude is included in suffering as suffering produced by change. It is easy to understand the two forms of suffering mentioned above. No one will dispute them. This aspect of the First Noble Truth is more popularly known because it is easy to understand. It is common experience in our daily life. But the third form of suffering as conditioned states is the most important philosophical aspect of the First Noble Truth, and it requires some analytical explanation of what we consider as a ‘being’, as an ‘individual’ or as ‘I’. What we call a ‘being’, or an ‘individual’, or ‘I’, according to Buddhist philosophy, is only a combination of ever-changing physical and mental forces or energies, which may be divided into five groups or aggregates.

dhīro bāle avekkhati: The sorrowless Arahants look compassionately with their Divine Eye upon the ignorant folk, who, being subject to repeated births, are not free from sorrow.

When an understanding one discards heedlessness by heedfulness, he, free from sorrow, ascends to the palace of wisdom and surveys the sorrowing folk as a wise mountaineer surveys the ignorant groundlings.