Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 273-276:

maggān’aṭṭhaṅgiko seṭṭho saccānaṃ caturo padā |

virāgo seṭṭho dhammānaṃ divipadānañca cakkhumā || 273 ||

eso’va maggo natth’añño dassanassa visuddhiyā |

etamhi tumhe paṭipajjatha mārass’etaṃ pamohanaṃ || 274 ||

etamhi tumhe paṭipannā dukkhass’antaṃ karissatha |

akkhāto ve mayā maggo aññāya sallasatthanaṃ || 275 ||

tumhehi kiccaṃ ātappaṃ akkhātāro tathāgatā |

paṭipannā pamokkhanti jhāyino mārabandhanā || 276 ||

273. Of paths the Eight-fold is the best, of truths the statements four, the passionless of teachings best, of humankind the Seer.

274. This is the path, no other’s there for purity of insight, enter then upon this path bemusing Māra utterly.

275. Entered then upon this path you’ll make an end of dukkha. Freed in knowledge from suffering’s stings the Path’s proclaimed by me.

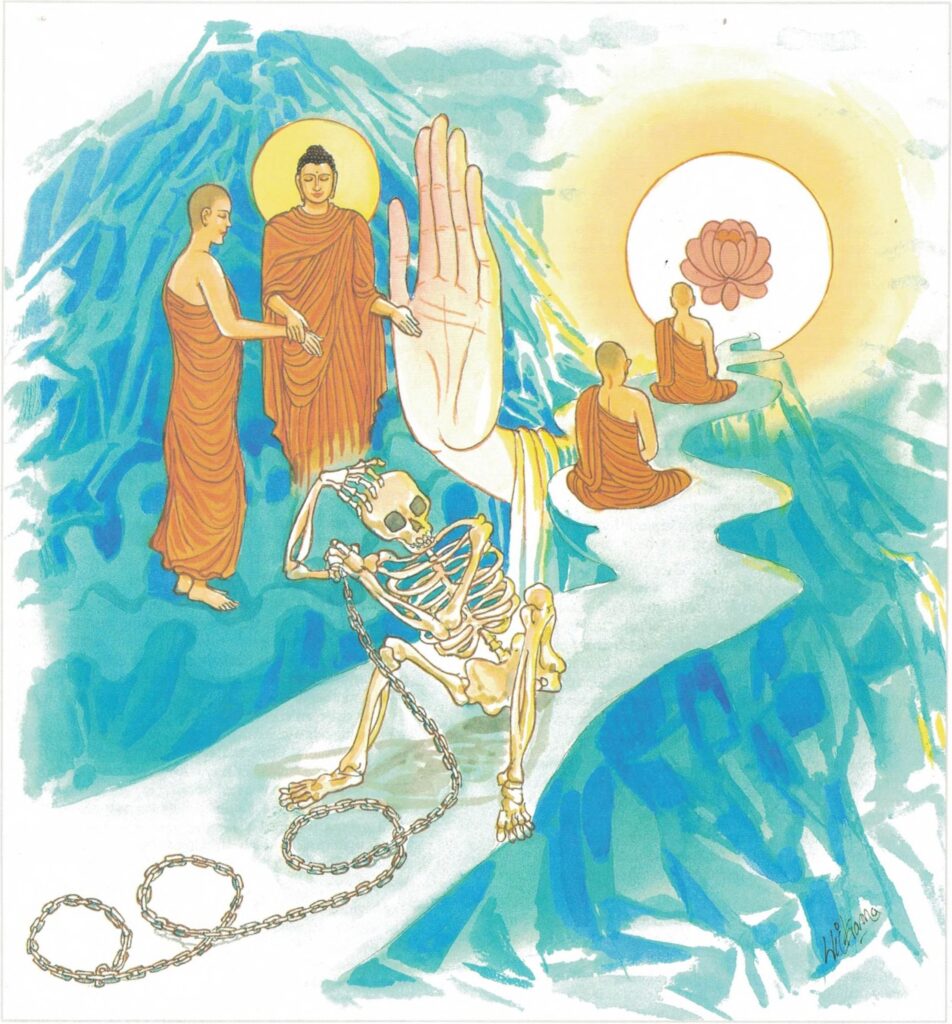

276. Buddhas just proclaim the Path but you’re the ones to strive. Contemplatives who tread the Path are freed from Māra’s bonds.

The Story of Five Hundred Monks

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses with reference to five hundred monks.

The story goes that once upon a time the Buddha, after journeying through the country, returned to Sāvatthi and seated himself in the hall of Dhamma. When he had taken his seat, these five hundred monks began to talk about the paths over which they had travelled, saying, “The path to such and such a village is smooth; to such and such a village, rough; to such and such a village, covered with pebbles; to such and such a village, without a pebble. After this manner did they discuss the paths over which they had travelled. The Buddha, perceiving that they were ripe for arahatship, went to the hall of Dhamma, and seating himself in the seat already prepared for him asked, “Monks, what is the present subject of discussion as you sit here together?” When they told him, he said, “Monks, this is a path foreign to our interests; one who is a monk should address himself to the noble path, for only by so doing can he obtain release from all sufferings.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 273)

maggānaṃ aṭṭhangiko seṭṭho saccānaṃ caturo padā

dhammānaṃ virāgo seṭṭho dipadānaṃ ca cakkhumā

maggānaṃ [maggāna]: of the paths; aṭṭhangiko maggo [magga]: the eight-fold (path is); seṭṭho [seṭṭha]: is greatest; saccānaṃ [saccāna]: of truths; caturo padā: four noble truths (are the greatest); dhammānaṃ [dhammāna]: of the states of being; virāgo [virāga]: detachment-Nibbāna; dipadānaṃ [dipadāna]: of the two-footed; cakkhumā: one who possesses eyes (the Buddha) is the greatest

Of all paths, the eight-fold path is the greatest. Of the truths, the greatest are the four noble truths. Detachment (Nibbāna) is the greatest among all states. And of all those who are two-footed ones, one who possesses eyes, the Buddha is the greatest.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 274)

visuddhiyā dassanassa eso eva maggo natthi añño

tumhe etamhi paṭipajjatha etaṃ mārassa pamohanaṃ

visuddhiyā dassanassa: for the clarity of insight; eso eva maggo [magga]: this is the only path; natthi añño: no other (path); tumhe: (therefore) you; etamhi: this path; paṭipajjatha: follow; etaṃ: this path; mārassa: death; pamohanaṃ [pamohana]: will bewilder

This is the path. There is no other for the achievement of clarity of insight. You must follow this path to the total bewilderment of Māra.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 275)

etamhi patipannā tumhe dukkhassa antaṃ karissatha

mayā sallasanthanaṃ maggo aññāya ve akkheto

etamhi: this path; patipannā: following; tumhe: by you; dukkhassa: of suffering; antaṃ karissatha: (you) must make an end of; mayā: by me; sallasanthanaṃ [sallasanthana]: for the extraction of the arrow (from the body); maggo [magga]: the path; aññāya: having known; ve: certainly; akkheto [akkheta]: proclaimed

If you follow this path, you will reach the termination of suffering. This path has been revealed by me, after realizing the extraction of arrows.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 276)

tumhehi ātappaṃ kiccaṃ Tathāgatā akkhātāro

paṭipannā jhāyino Mārabandhanā pamokkhanti

tumhehi: by yourself; ātappaṃ [ātappa]: the effort (to get rid of blemishes); kiccaṃ [kicca]: should be made; Tathāgatā: the wayfarers (the Buddhas); akkhātāro [akkhātāra]: proclaimers (of Nibbāna); paṭipannā: the followers of the path; jhāyino [jhāyina]: meditators; Mārabandhanā: from the shackles of death; pamokkhanti: get fully released

The effort must be made by yourself. The Buddhas (the Teachers) only show the way and direct you. Those contemplative meditators who follow the path, fully and totally escape the snares of death.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 273-276)

Eso va maggaṃ natthi añño dassanassa visuddhiyā: There is no other path for purity of vision than just this one. Those who travel along the path indicated by the Buddha to reach purity of vision, have to practice the technique of meditation, by which purity of vision is achievable.

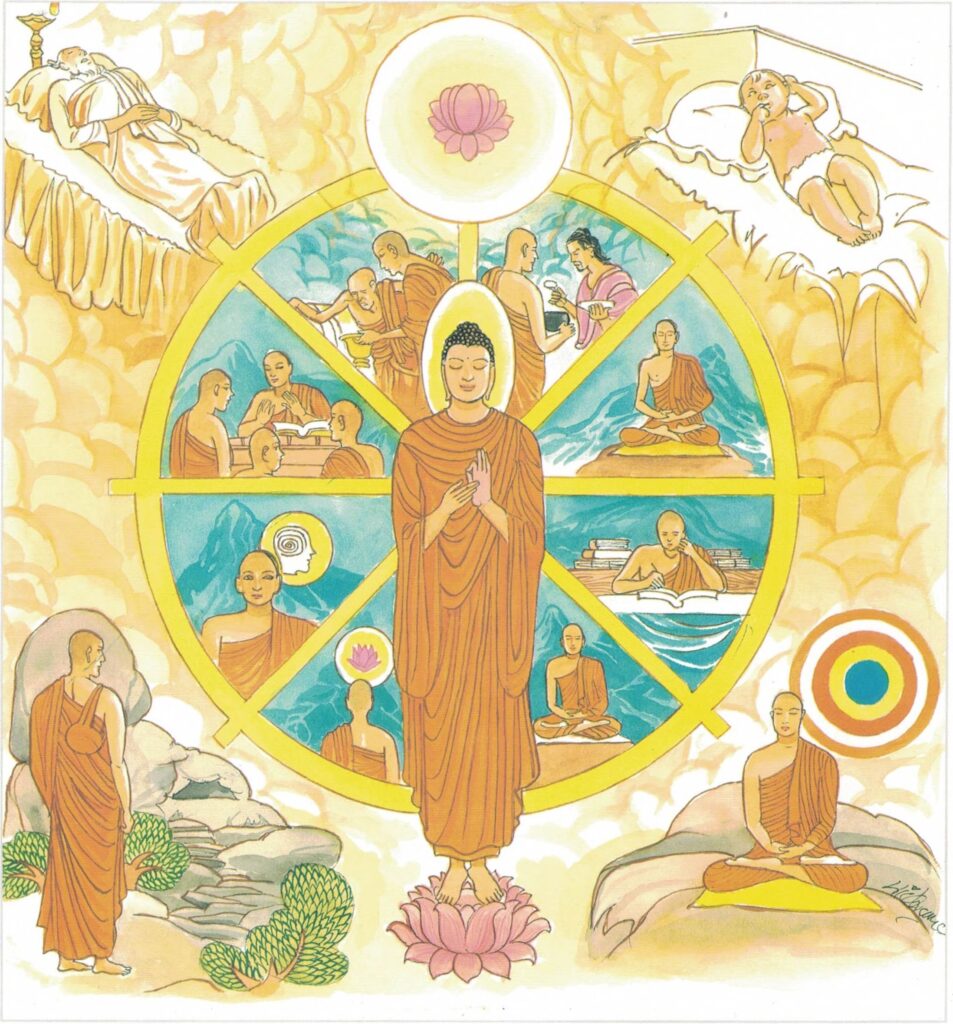

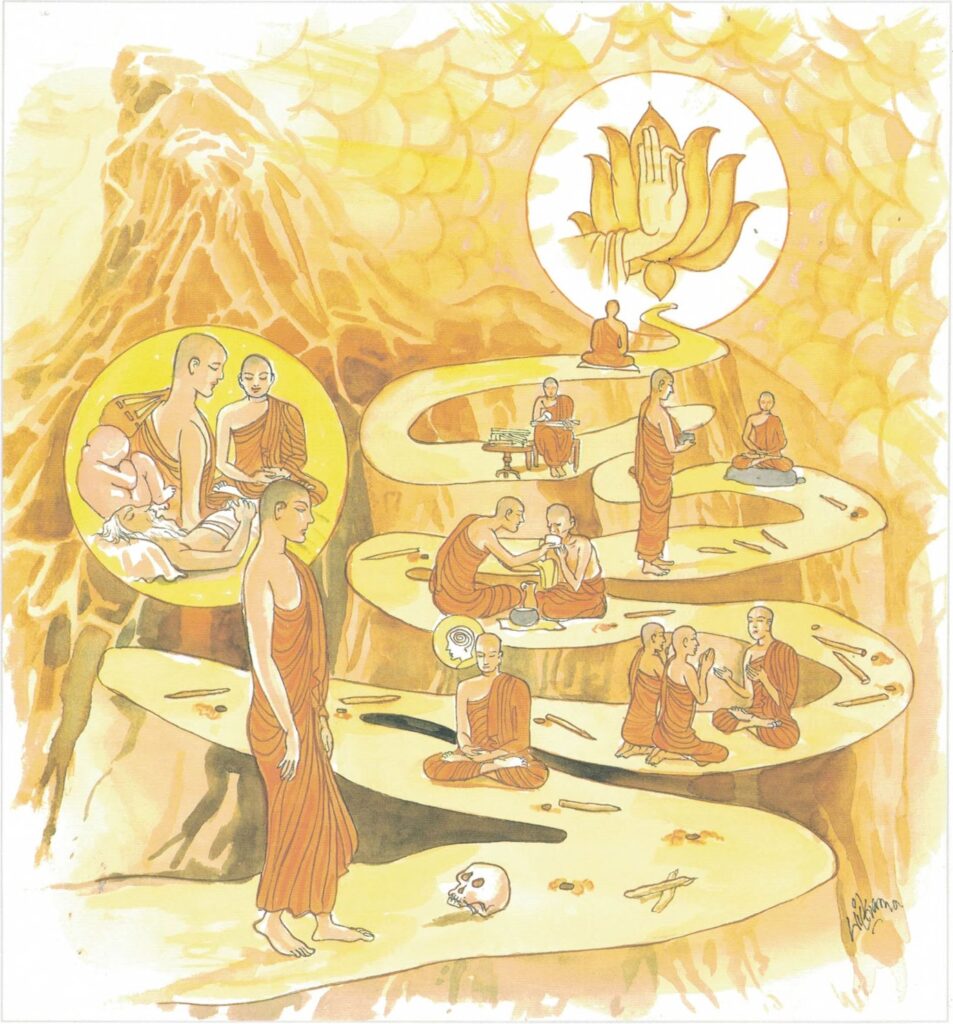

A truth-seeker attains this stage through seven stages. In consequence, this process is characterized as sapta visuddhi (seven stages of purity). The seven stages of purity are:

- Sīla visuddhi (purity of morals)

- Citta visuddhi (purity of mind)

- Diṭṭhi visuddhi (purity of views)

- Kankhāvitarana visuddhi (purity of the conquest of doubts)

- Maggāmagga ñaṇadassana visuddhi (purity of knowledge and insight into the right and wrong path)

- Patipadā ñaṇadassana visuddhi (purity of knowledge and insight into progress)

- Ñaṇadassana visuddhi (purity of knowledge and insight into the noble path).

(1) Sīlavisuddhi–purity of morals–

The person with an impure character has always a fear that others will find fault with him or bring shame on him or take revenge on him. Similarly, his own conscience troubles him, saying that he has done something wrong. The mind of the non-virtuous person is debilitated by such thoughts. The person whose mind is thus debilitated will not gain any results if he turns to meditation. Like a tree which is planted on infertile soil, his mind will not be able to attain wisdom by concentration. Therefore, a yogāvacara, if he wishes to concentrate and reach an exalted state or attain the correct path by meditation, must first of all prepare the way for meditation, just as a farmer prepares the land for cultivation. If he is a layman he must act according to the ways of a layman. If he is a monk he must act according to the ways of a monk. The layman if he wishes to be virtuous must at the minimum observe the five precepts. Virtue will arise when all defilements are eradicated. Therefore, he must try his best to purify himself by leading a virtuous life instead of feeling that he is unable to lead a virtuous life and giving up meditation.

(2) Cittavisuddhi–purity of mind–

It is very difficult to realize the nature of nāma rūpa (mind and matter) as they are covered by illusions of the existence of individuals, males, females, persons and other concepts. The knowledge of nāma rūpa which we gather from books is insufficient for us to eradicate our defilements and attain the path leading to salvation and enlightenment. Knowledge from books is knowledge at second-hand which has not been experienced, as it has not been realized by the individual himself. It is not self-realization.

To attain the correct path we require more than a knowledge from books; we require a clear philosophy which we can comprehend for ourselves. This philosophy can be realized only by meditation and meditation alone. Just as a person sharpens his knife before he begins to cut anything hard, in order to understand the nature of nāma rūpa the yogāvacara must first of all prepare his mind. When his mind is free from hindrances, he attains citta visuddhi.

To purify our minds we must increase our powers of concentration. The nature of the mind is not to concentrate for a long time on one object but to wander from object to object. The person who is travelling at a very fast speed is unable to comprehend any one thing he sees on the side of the road as his mind, which has not attained concentration and wanders from object to object, cannot comprehend the true nature of things. When, by insight meditation, we are concentrating on the real nature of mind and matter, if the mind does not abide for a long time on this, it will begin to wander from object to object very fast. Such a mind will not be able to grasp the ultimate reality. If he is unable to do so, the wisdom of insight meditation would not arise in him quickly. Therefore, if he wishes to develop insight wisdom quickly, he must concentrate and prepare his mind for such a venture.

After diligent practice a person will attain the ability to keep his mind concentrated on one object for a long time. This ability of mind concentration is attained by mental discipline (samādhi). Without allowing in the intervening period anything else to enter his mind, if he is able to keep his mind concentrated on one object for a long time he is in a state of trance. There are also yogāvacaras who, at the very beginning, develop a high state of insight wisdom without developing concentration. Therefore, there is no harm if those who do not like to develop concentration can develop pure insight wisdom. Of those who develop insight wisdom after concentration there are some who attain this insight wisdom while they are in a trance. Still others develop concentration up to a certain point and when they have reached the first stage of concentration they are able to attain to insight wisdom. Others develop concentration and insight wisdom at the same time and meditate making use of both these factors at the same time. Of these systems, to achieve insight wisdom after attaining a state of trance does not suit the present day. If one does so it may happen that for a long time one may not be able to achieve insight wisdom.

It is our opinion that at first a person must develop his concentration and thereafter adopt the method of developing both concentration and insight wisdom. This seems to be the best system which can be followed.

(3) Diṭṭhivisuddhi–Purity of views–

To purify one’s mind by meditating on the Buddha or by undertaking any other system of meditation one must commence with diṭṭhi visuddhi bhāvanā. What is Ātma diṭṭhi drūsti? Ātma diṭṭhi drūsti means not considering mind and matter as mind and matter, myself as myself, mother as mother, father as father, brother as brother, sister as sister, an enemy as an enemy, a friend as a friend, and considering other varied individuals as beings in the same character and treating them and accepting them as such. This is Ātma drūsti. Sakkāyadiṭṭhi is another name for it. (sakkāya –diṭṭhi, means belief in a soul or self). Insight wisdom means considering the nature of mind and matter as mind and matter itself and not as oneself or as father, mother or any other being. This insight wisdom which is free from ātma drūsti is called diṭṭhi visuddhi. The brief explanation of diṭṭhi visuddhi is purity of wisdom.

The beginning of insight meditation is diṭṭhi visuddhi bhāvanā. The yogāvacara will have to spend a very long time to acquire this diṭṭhivisuddhi–pure wisdom. He must master correctly the diṭṭhivisuddhi. If the yogāvacara tries to go forward without correctly mastering the diṭṭhivisuddhi his meditation practice will be confused. This should be mastered in the manner in which the doctrine of mind and matter can be seen as myself, mother or father or any other individual just as we peel the bark of a banana tree and thus make our wisdom into separate sections. This meditation has to be developed till we get rid of the ideas which we formerly entertained in our minds as mine, my father, my brother, my son, my wife–i.e., the conception of considering them as beings and individuals and until we can see and analyse them as I am not I, and my father is not my father, and consider them as just constituents of matter and mind.

According to Buddhist philosophy there is no permanent, unchanging spirit or entity which we can consider as self or soul or ego in contradistinction to matter, and consciousness or viññāna should not be considered as spirit as opposed to matter. It should be particularly emphasised, because a wrong conception that consciousness is a sort of self which continues as a permanent substance throughout life has persisted throughout the ages.

The Buddha has explained it further by an example. The nature of a fire is described by the material on account of which it burns. If it burns on account of straw it is called a straw fire. So consciousness is described according to the condition through which it arises.

The Buddha has described in unequivocal terms that consciousness is dependent on matter, sensation, perception and mental conceptions and that it cannot subsist independently of them. Consciousness exists with matter as its means (rūpāyaṃ), matter as its object (rūpārammaṇa), matter as its support–(rūpapatiṭṭhitaṃ) and seeking happiness it may grow, increase and develop. Consciousness may exist having sensation as its means or mental conception as its support, and seeking happiness it may grow, increase and develop.

If a man says “I shall show the coming, the going, the disappearance, the arising, the growth, the increase or the development, or consciousness apart from matter, sensation, perception and mental conception,” he would be speaking of something that does not exist. In brief, the five aggregates (Pañcakkhandha) can be described thus. What we can describe as a being or an individual or I, is only a convenient name or a label given to the combination of these five groups. They are all impermanent and subject to constant change. Whatever is impermanent is sorrow, The true meaning of the Buddha’s words is, briefly, this: The five aggregates of attachment are equal to sorrow. For two consecutive moments they are not the same. Therefore, A is not equal to A. They are a flux or stream of momentary arising or disappearing.

“O’ Brahmaṇa, it is just like a mountain river flowing far and swift taking everything along with it. There is no moment, no instant or second when it ceases to flow, but it continues to flow. Similarly, is human life like a mountain river.” In these words the Buddha explained to Raṭṭhapāla that the world is in continuous flux and is impermanent.

As one thing disappears it conditions the appearance of the next in a series of cause and effect. There is no unchanging substance within them. There is nothing behind them that can be described as a permanent self, or soul. It will be agreed by every one that neither matter nor sensation nor perception, nor any of these mental activities nor consciousness can be really called “I”. But these independent five physical and mental aggregates are working together in combination as a physio-psychological machine to give the idea of “I”. But this is an erroneous idea, a mental conception which is nothing but one of those fifty-two mental conceptions of the fourth aggregate, which is the idea of self.

These five aggregates taken together are popularly called suffering itself. There is no other being or myself standing behind these five aggregates who experiences dukkha.

Kammassa Kārakā natthi–vipākassaca vedako

Suddhadhammā pavattanti–evetaṃ sammadassanaṃ

(4) Kaṅkhāvitāraṇa visuddhi–purity of the conquest of doubts–

To obtain the supramundane state, doubt is a great hindrance. To eradicate the origin of anything we must discover its causes. The cycle of rebirth can be destroyed by finding out its causes.

(5) Maggāmagga ñāṇadassana visuddhi–purity of knowledge and insight into right and wrong path.–

Here, magga means the correct system of meditation. To attain this state of wisdom one should observe the tilakkhaṇa meditation. When the nāma and rūpa are taken together they are referred to as saṃkhāra. The conditioned things (saṃkhāras) referred to in the paticca samuppāda refer to cause and effect of the karmic actions. Although we hear the words anicca, dukkha and anatta very often, we do not realise that they have such a deep meaning. We know that all living beings are subject to death, but this is insufficient for vipassanā bhāvanā. It is not enough to know only the attributes of sorrow. This is difficult for us to understand because our mind is overwhelmed by delusion.

(6) Paṭipadāñaṇadassana visuddhi–purity of knowledge and insight into progress.–

The disciple who is free from the harmful influences of the defilements and has gained the purity and knowledge of the right and wrong paths in the previous stage, develops his insight to its culmination in this final stage through the systematic and steadfast progress of deeper understanding. This is termed paṭipadā–gradual progress–which consists of the nine-fold insight wisdom leading to the realisation of transcendental states.

(7) Ñāṇadassana visuddhi–purity of knowledge and insight into the noble path.–

The four wisdom of knowing the path to four stages of higher attainment make up this.