Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 270:

na tena ariyo hoti yena pāṇāni hiṃsati |

ahiṃsā sabbapāṇānaṃ ariyo’ti pavuccati || 270 ||

270. By harming living beings one is not a ‘Noble’ man, by lack of harm to all that live one is called a ‘Noble One’.

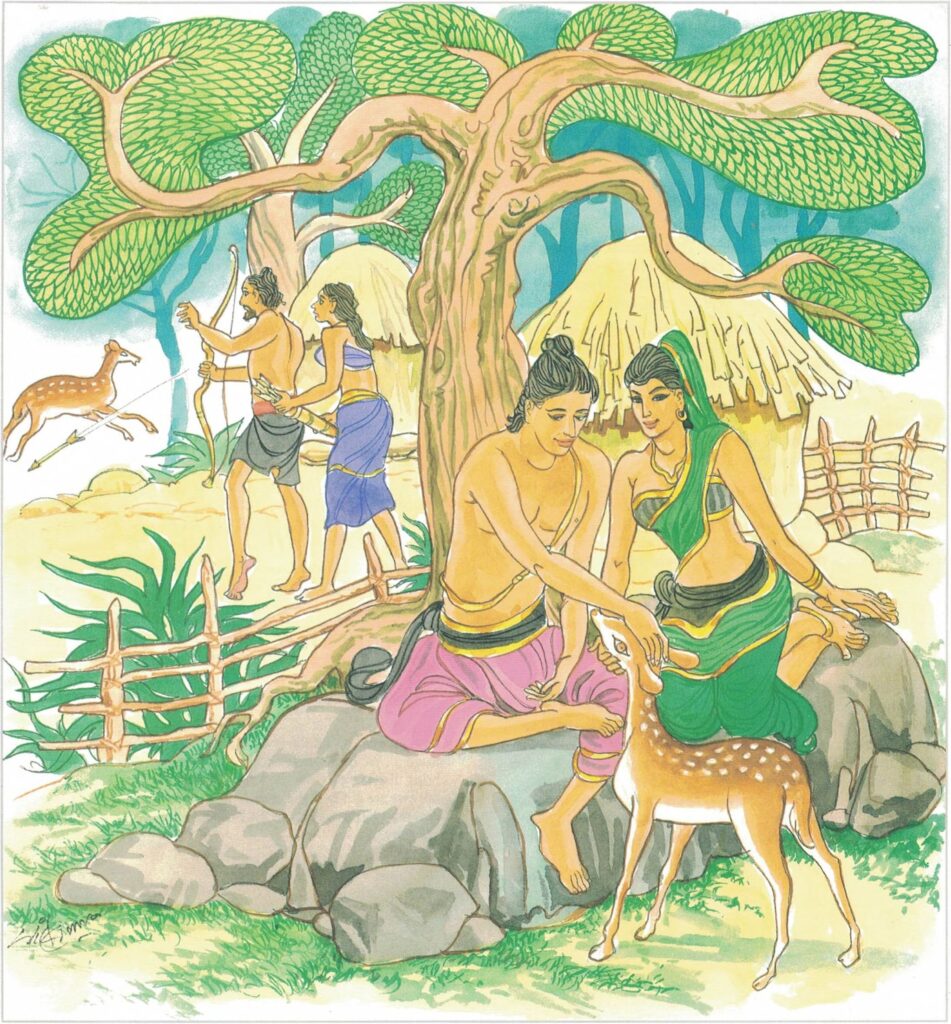

The Story of a Fisherman Named Ariya

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse with reference to a fisherman named Ariya.

Once, there was a fisherman who lived near the north gate of Sāvatthi. One day through his supernormal power, the Buddha found that time was ripe for the fisherman to attain sotāpatti fruition. So on his return from the alms-round, the Buddha, followed by the monks, stopped near the place where Ariya was fishing. When the fisherman saw the Buddha, he threw away his fishing gear and came and stood near the Buddha. The Buddha then proceeded to ask the names of his monks in the presence of the fisherman, and finally, he asked the name of the fisherman. When the fisherman replied that his name was Ariya, the Buddha said that the noble ones (ariyas) do not harm any living being, but since the fisherman was taking the lives of fish he was not worthy of his name. At the end of the discourse, the fisherman attained sotāpatti fruition.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 270)

yena pāṇāni hiṃsati tena ariyo na hoti

sabbapāṇānaṃ ahiṃsā ariyo iti pavuccati

yena: if someone; pāṇāni: living beings; hiṃsati: hurts; tena: due to that; ariyo [ariya]: a noble person; na hoti: (he) does not become; sabbapāṇānaṃ [sabbapāṇāna]: all living beings; ahiṃsā: does not hurt; ariyo iti pavuccati: (because of that) he is called a noble one

A person who hurts living beings is not a noble human being. The wise person, who does not hurt any living being is called ariyo, a noble individual.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 270)

ahiṃsā: non-violence. The all-pervading spirit of Buddhist ethics ahiṃsā. This concept was interpreted in an immortal manner by Emperor Asoka, whose missionaries took the Word of the Buddha to most centres of the then-known world. For four years Asoka, though in fact the ruler of his domains, had to wage a relentless struggle to subjugate them and further enlarge his territories, bringing Kālinga too under his sway. This was Asoka’s digvijaya or war of military conquest. It was only after the completion of this digvijaya of Asoka that, stricken by remorse at the terrible magnitude of the human slaughter involved, he embarked on a policy of Dharmavijaya or conquest by righteousness, imbued with the high ideals of love and compassion taught by the Buddha’s Dhamma. Thereafter he was known as Dharmāsoka.

Having turned to the path of righteousness, after embracing Buddhism, Asoka set about spreading the faith both in his empire and in far-flung lands abroad. He had his two children ordained, his son Mahinda and his daughter Sanghamittā, sending the former to propagate the faith in Sri Lanka, while Sanghamittā came later with the sapling of the Mahā Bo Tree at Buddhagayā and established the Order of Buddhist Nuns.

The policy of Asoka was one which enjoined:

(1) ahiṃsā to all beings,

(2) refraining from harsh and rude speech,

(3) respecting parents, teachers and elders,

(4) having regard for brāhmins, priests and servants,

(5) leading a life of righteousness, which entails compassion, generosity, truthfulness, purity, gentleness, gratitude and spending according to one’s means,

(6) engaging in dharmayāthrā or pilgrimages,

(7) constructing of wells and ponds and the planting of fruits and medical herbs, and

(8) having filial regard and affection for one’s subjects.