Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 262-263:

na vākkaraṇamattena vaṇṇapokkharatāya vā |

sādhurūpo naro hoti issukī maccharī saṭho || 262 ||

yassa c’etaṃ samucchinnaṃ mūlaghaccaṃ samūhataṃ |

sa vantadoso medhāvī sādhurūpo’ti vuccati || 263 ||

262. Not by eloquence alone or by lovely countenance is a person beautiful if jealous, boastful, mean.

263. But ‘beautiful’ is called that one in whom these are completely shed, uprooted, utterly destroyed, a wise one purged of hate.

The Story of Some Monks

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses with reference to some monks.

For once upon a time certain Venerables saw some young monks and novices dyeing robes and performing the other duties for their preceptors. Thereupon they said to themselves, “We ourselves are clever at putting words together, but for all that, receive no such attentions. Suppose now we were to approach the Buddha and say to him, ‘Venerable, when it comes to the letter of the sacred word, we too are expert; give orders to the young monks and novices as follows–Even though you have learned the Law from others, do not rehearse it until you have improved your acquaintance with it under these Venerables.’ Thus will our gain and honour increase.”

Accordingly, they approached the Buddha and said to him what they had agreed upon. The Buddha listened to what they had to say and became aware of the following, “In this Religion, according to tradition, it is entirely proper to say just this. However, these Venerables seek only their own gain.” So he said to them, “I do not consider you accomplished merely because of your ability to talk. But that man in whom envy and other evil qualities have been uprooted by the Path of arahatship, he alone is truly accomplished.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 262)

vākkaraṇamattena vaṇṇapokkharatāya vā

issukī maccharī saṭho naro sādhurūpo na hoti

vākkaraṇamattena: merely because of the ornate speech; vaṇṇapokkharatāya vā: or by the comeliness of appearance;issukī: envious; maccharī: greedy; saṭho [saṭha]: devious; naro: man; sādhurūpo [sādhurūpa]: an acceptable person; na hoti: does not become.

Merely because of one’s verbal flourishes, impressive style of speaking, or charming presence, a person who is greedy, envious and deceitful does not become an acceptable individual.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 263)

yassa etaṃ samucchinnaṃ ca mūlaghaccaṃ samūhataṃ

vantadoso medhāvi so sādhurūpo iti vuccati

yassa: if by one; etaṃ: all these evils; samucchinnaṃ [samucchinna]: are being uprooted; ca: and; mūlaghaccaṃ [mūlaghacca]: eradicated; samūhataṃ [samūhata]: fully destroyed; vantadoso [vantadosa]: he who has given up all these evils; medhāvi: wise; so: that wise person; sādhurūpo iti: a virtuous one; vuccati: is called

If an individual has uprooted and eradicated all these evils and has got rid of blemishes, such a person is truly an acceptable individual.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 262-263)

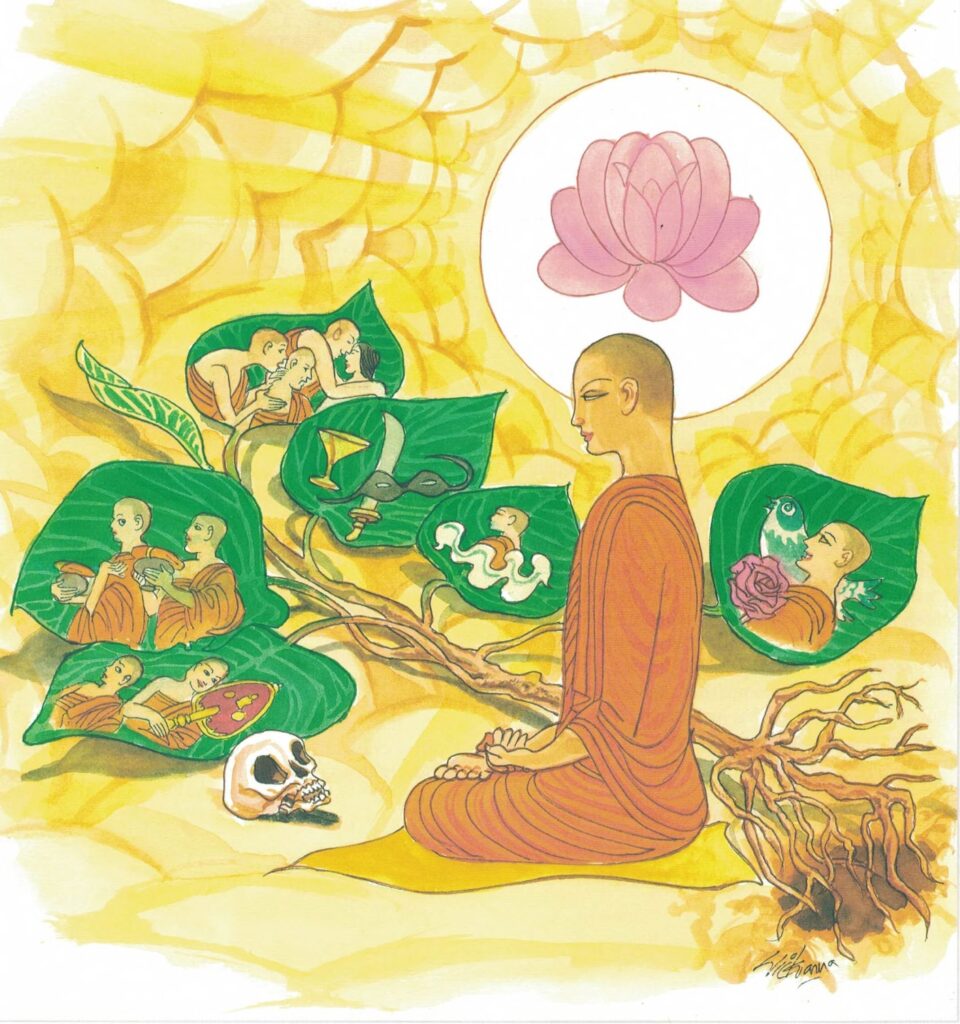

Buddha as teacher: In these verses, the Buddha admonishes elder monks who believe that they are the right persons to teach the young monks just because they can use words deftly. The Buddha says it takes more than the clever use of words to be an expert spiritual teacher. Throughout his life, Buddha taught and guided people in spiritual matters–and even in worldly matters at times. He did not only preach, but also lived according to what he preached.

The Buddha was the embodiment of the virtues that he preached. During his successful and eventful ministry of forty-five years, he translated all his words into action. At no time did he ever express any human frailty or any base passion. Yet the Buddha’s moral code is the most perfect which the world has ever known.

For more than twenty-five centuries, millions of people have found inspiration and solace in his Teaching. His Teaching still beckons the weary pilgrim to the security and peace of Nibbāna.

To Buddha, religion was not a bargain but a way to enlightenment. He did not want followers with blind faith; he wanted followers who could think freely and wisely.

There was never an occasion when the Buddha expressed any unfriendliness towards a single person. Not even to his opponents and worst enemies did the Buddha express any unfriendliness. There were a few prejudiced minds who turned against the Buddha and tried to kill him; yet the Buddha never treated them as enemies. The Buddha once said, “As an elephant in the battle field endures the arrows that are shot into him, so will I endure the abuse and unfriendly expression of other people.”

In the annals of history, no man is recorded as having so consecrated himself to the welfare of all living beings as did the Buddha. From the hour of His enlightenment to the end of His life, He strove tirelessly to elevate mankind. He slept only two hours a day. Though twenty-five centuries have gone since the passing away of the great Teacher, His message of love and wisdom still exists in its pristine purity. This message is still decisively influencing the destinies of humanity. He was the most compassionate one who illuminated this world with lovingkindness.

After attaining Nibbāna, the Buddha left a deathless message that is still living with us in the world today. Today we are confronted by the tenable threat to world peace. At no time in the history of the world was His message more needed than it is now.

The Buddha was born to dispel the darkness of ignorance and to show the world how to get rid of suffering and disease, decay and death and the worries and miseries of living beings.

No amount of talk and discussion not directed towards right understanding will lead to deliverance. This was the principle that guided the Buddha’s Ministry.

The Buddha was not concerned with some meta-physical problems which only confuse man and upset his mental equilibrium. Their solution surely will not free mankind from misery and ill. That was why the Buddha hesitated to answer such questions, and at times refrained from explaining those which were often wrongly formulated. The Buddha was a practical Teacher. His sole aim was to explain in all its detail the problem of dukkha, suffering, the universal fact of life, to make people feel its full force, and to convince them of it. He has definitely told us what He explains and what He does not explain.