Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 256-257:

na tena hoti dhammaṭṭho yenatthaṃ sahasā naye |

yo ca atthaṃ anatthañca ubho niccheyya paṇḍito || 256 ||

asāhasena dhammena samena nayatī pare |

dhammassa gutto medhāvī dhammaṭṭho’ti pavuccati || 257 ||

256. Whoever judges hastily does Dhamma not uphold, a wise one should investigate truth and untruth both.

257. Who others guide impartially with carefulness, with Dhamma, that wise one Dhamma guards, a ‘Dhamma-holder’s’ called.

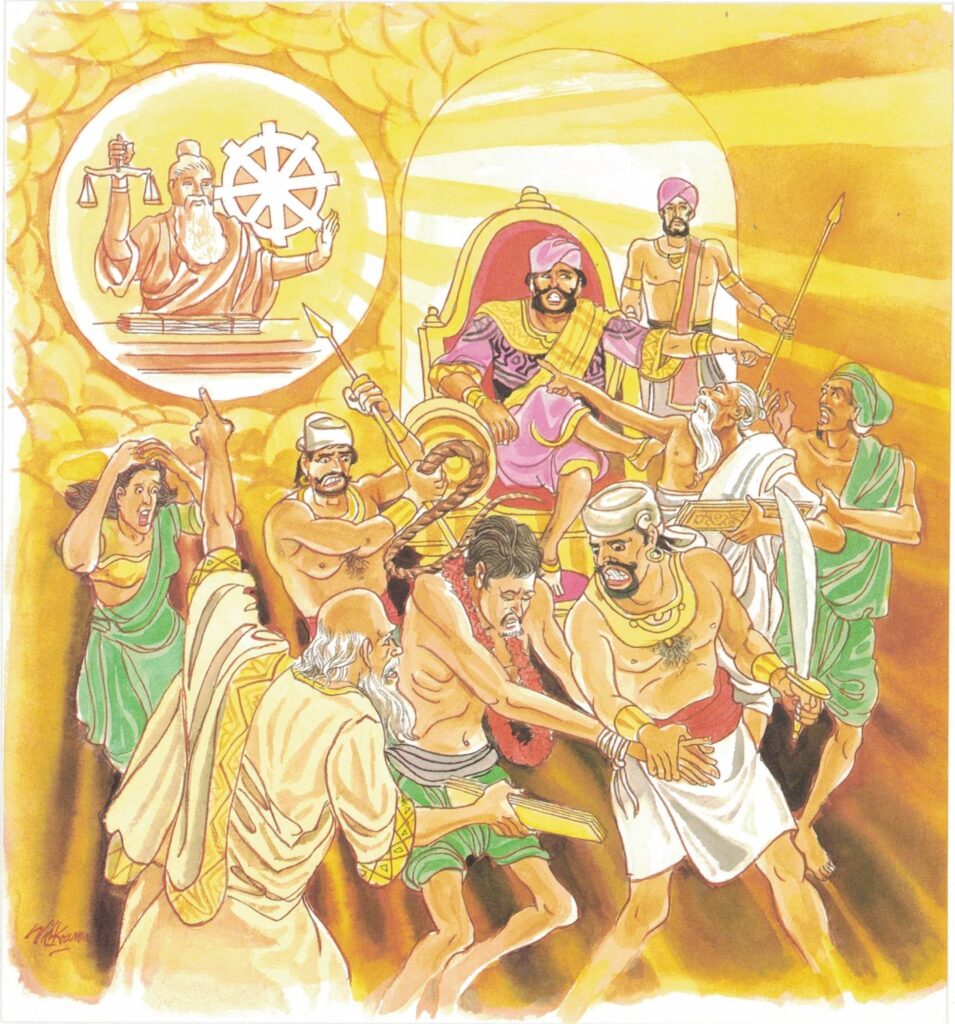

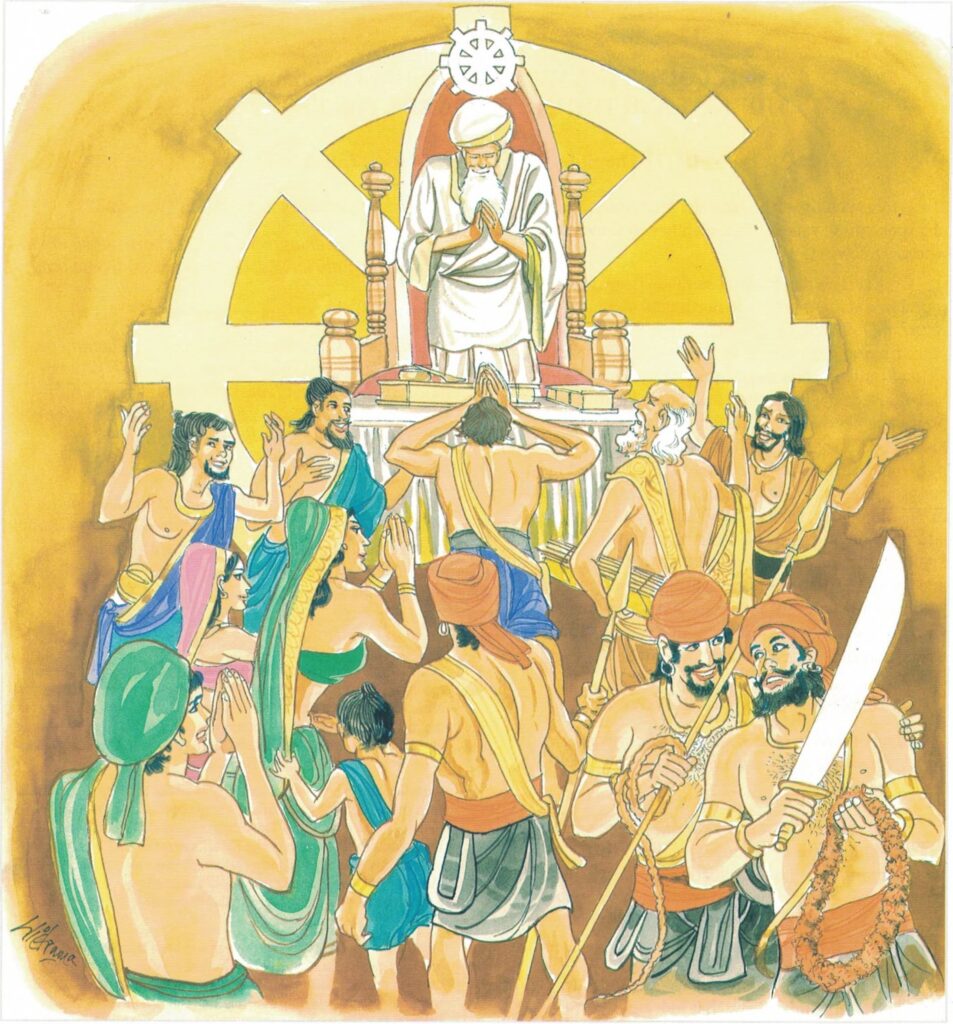

The Story of the Judge

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses with reference to some judges who were corrupt.

On a certain day the monks made their alms-round in a settlement at the north gate of Sāvatthi, and returning from their pilgrimage to the monastery, passed through the center of the city. At that moment, a cloud came up, and the rain began to fall. Entering a hall of justice opposite, they saw lords of justice taking bribes and depriving lawful owners of their property. Seeing this, they thought, “Ah, these men are unrighteous! Until now we supposed they rendered righteous judgments.” When the rain was over, they went to the monastery, saluted the Buddha, and sitting respectfully on one side, informed him of the incident. Said the Buddha, “Monks, they that yield to evil desires and decide a cause by violence, are not properly called justices; only they that penetrate within a wrong, and without violence render judgement according to the wrong committed, are properly called justices.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 256)

yena atthaṃ sahasā naye tena dhammaṭṭho na hoti

paṇḍito yo ca atthaṃ ca anatthaṃ ca ubho niccheyya

yena: if for some reason; atthaṃ [attha]: the meaning; sahasā naye: falsely adjudged; tena: by that; dhammaṭṭho [dhammaṭṭha]: based on justice; na hoti: he is not; paṇḍito [paṇḍita]: the wise person; yo ca: in his way; atthaṃ ca: justice; anatthaṃ ca: and the injustice; ubho: these two; niccheyya: decides

If for some reason someone were to judge what is right and wrong, arbitrarily, that judgement is not established on righteousness. But, the wise person judges what is right and what is wrong discriminately, without prejudice.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 257)

asāhasena dhammena samena pare nayatī dhammassa

gutto medhāvī dhammaṭṭhito ti pavuccati

asāhasena: without being arbitrary; dhammena: righteously; samena: impartially; pare: others; nayatī: judges; dhammassa: by the law of righteousness; gutto [gutta]: protected; medhāvi: that wise person; dhammaṭṭhito ti: one established in the righteous; pavuccati: is called

That wise person, who dispenses justice and judges others impartially, without bias, non-arbitrarily, is guarded by and is in accordance with the Law of Righteousness. Such a person is described as well established in the Dhamma.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 256-257)

dhammaṭṭhito: one who is established in righteousness. The Buddha has always made it clear that an intellectual appreciation of the intricacies of the Dhamma is not all fruitful unless one is firmly established in the Dhamma–to say one should organize his style of life in accordance with the Dhamma. At this stage, it is essential to know what is the word of the Buddhas.

If one wishes to know what were the words of the Buddha Himself, then the books about Buddhism will not suffice and one should turn to the records of His Teachings collected in the Pāli canon. This canonical collection of the Buddha word cannot be compressed into one handy volume although there are many brief formulations of the Dhamma from different points of view. As the Buddha taught for forty-five years, so the records of His Dhamma and the Vinaya are compendious.

Most of the books in the Pāli canon have been translated once, very few have two or three translations, while only one book has been translated several times into English (the Dhammapada). The summary below includes only the canon in Pāli, the language spoken by the Buddha, the works of which are complete. Sanskrit canons are either fragmentary, existing only in Chinese and Tibetan translations and untranslated into English, or else are composed of much later works which, although they are often ascribed to Gotama the Buddha, can hardly be his words.

The Pāli canon was codified in the first council after the Buddha’s passing (parinibbāna). A few items have been added at later dates. This canon was then transmitted by memorizers–monks who learned portions of the discourses by heart from their Teachers, and in turn transmitted the memorized text to their monk-pupils. This verbal transmission lasted for about four hundred years. Many brāhmins trained in the art of committing texts to memory became monks and faithfully transmitted the canon in Pāli language until the time of the fourth council in Sri Lanka.

Due to the disturbed conditions of those times, the senior monks decided to commit the whole canon to writing. They assembled for this purpose and wrote the Buddha’s word using the metal stylus to inscribe ola palm leaves. Since that time the canon has been copied using the same materials until printed editions began to appear at the end of the nineteenth century. The first complete printed edition was published by order of King Rāma the Fifth (Chulalongkorn) using the Thai script.

In the West, the Pāli Text Society was founded by T. W. Rhys Davids in 1881, for the publication of the entire canon in Latin-script. This is now complete and most of it has also been translated into English and published by that society.

The canon is composed of the following sections and subsections. The renderings in English of the Pāli names for them are the titles of the published translations of the Pāli Text Society (PTS) unless otherwise stated.

I. Vinaya–Pitaka: “The Book of the Discipline” (lit.: Volume of Discipline) six books in complete translation.

(1) Bhikkhu–vibhanga–the matrix of discipline for monks.

(2) Bhikkhunī–vibhanga–the matrix of discipline for nuns.

(3) Mahāvagga–the great collection of miscellaneous disciplines.

(4) Cullavagga–the lesser collection of miscellaneous disciplines.

(5) Parivāra–a summary composed in Sri Lanka.

(6) Bhikkhu-pātimokkha–the 227 fundamental training rules for monks (published by Mahamakut Press, Bangkok).

II. Sutta–Piṭaka: (lit.: The Volume of Discourses).

(1) Dīgha–nikāya–“Dialogues of the Buddha” (lit.: The Extended Collection) three books containing 34 long discourses.

(2) Majjhima–nikāya–“Middle Length Sayings” (lit.: The Middlelength Collection) three books containing 152 discourses of medium length.

(3) Saṃyutta–nikāya–“Kindred Sayings” (lit.: The Related Collection) five books containing 7,762 discourses arranged by subject.

(4) Anguttara–nikāya–“Gradual Sayings” (lit.: The One-further Collection) five books containing 9,557 discourses arranged in numerical groups from one to eleven.

(5) Khuddaka–nikāya–“Minor Anthologies” (lit.: Minor Collection) composed of fifteen separate works:

- Khuddakapātha–“Minor Readings” (and Illustrator–its commentary). A brief handbook of essentials.

- Dhammapada–(many illustrations) 26 chapters containing 423 inspiring Verses.

- Udāna–“Verses of Uplift”–inspired utterances.

- Itivuttaka–“As It Was Said”–a collection of short discourses.

- Sutta–nipāta–“Woven Cadences”–mostly discourses in verse.

- Vimānavatthu–“Stories of the Mansions”–accounts of the heavens.

- Petavatthu–“Stories of the Departed”–accounts of the ghosts.

- Theragāthā–“Psalms of the Brethren”–“The Venerables’ Verses”–inspired verse spoken by enlightened monks.

- Therīgāthā–“Psalms of the Sisters”–the same as above, but for nuns.

- Jātaka–“Jataka Stories”–550 past lives of the Buddha in three books (only verses are canonical, stories are commentary).

- Niddesa–ancient commentary on (v) above.

- Patisambhidāmagga–analytical work.

- Apadāna–no English translation of these past lives of disciples.

- Buddhavaṃsa–Two translations: “The Lineage of the Buddhas” and “The Chronicle of the Buddhas”.

- Cariyā–piṭaka–‘The Collection of Ways of Conduct’.

III. Abhidhamma–Piṭaka: (lit.: The Volume of Further Teachings) five books in translation so far.

(1) Dhammasanganī–‘Buddhist Psychological Ethics’.

(2) Vibhanga–‘The Book of Analysis’.

(3) Dhātukathā–‘The Discourse on Elements’.

(4) Puggalapaññatti–‘A Designation of Human Types’.

(5) Kathāwatthu–‘Points of Controversy’ added at the Third Council.

(6) Yamaka–Pairs.

(7) Paṭṭhāna–‘Conditional Relations’.

But for the practice and penetration of the Dhamma it is not necessary to read all the Buddha’s words and the extensive commentaries, though in some cases it may remain useful. The Buddha has said:

Better the single Dhamma Word by hearing which one dwells at peace,

Than floods of verse as thousand-fold profitless and meaningless.

(Dhammapada, Verse 102)