Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 225:

ahiṃsakā ye munayo niccaṃ kāyena saṃvutā |

te yanti accutaṃ ṭhānaṃ yattha gantvā na socare || 225 ||

225. Those sages inoffensive in body e’er restrained go unto the Deathless State where gone they grieve no more.

The Story of the Brāhmin who had been the ‘Father of the Buddha’

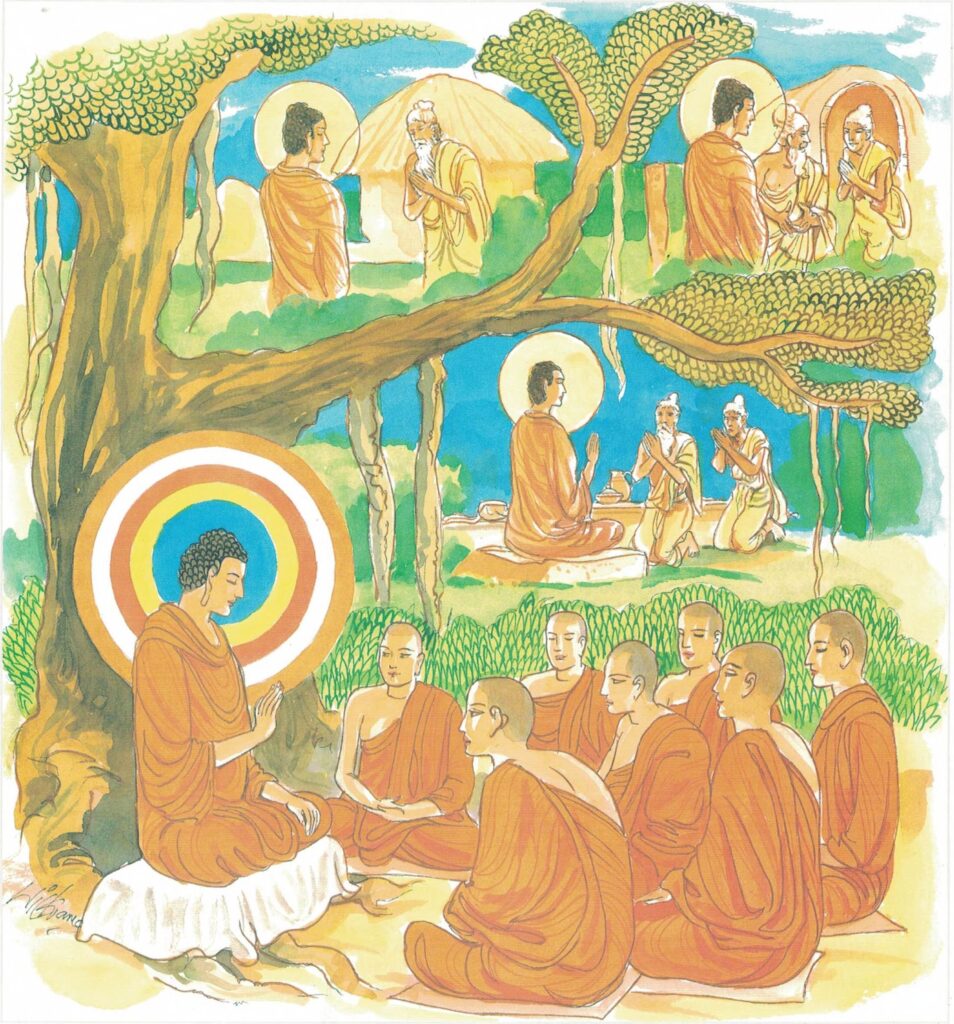

While residing at the Anjana Wood, near Sāketa, the Buddha spoke this verse with reference to a brāhmin, who claimed that the Buddha was his son.

Once, the Buddha accompanied by some monks entered the town of Sāketa for alms-food. The old brāhmin, seeing the Buddha, went to him and said, “O son, why have you not allowed us to see you all this long time? Come with me and let your mother also see you.” So saying, he invited the Buddha to his house. On reaching the house, the wife of the brāhmin said the same things to the Buddha and introduced the Buddha as “Your big brother” to her children, and made them pay obeisance to him. From that day, the couple offered alms-food to the Buddha every day, and having heard the religious discourses, both the brāhmin and his wife attained anāgāmi fruition in due course. The monks were puzzled as to why the brāhmin couple had said the Buddha was their son; so they asked the Buddha.

The Buddha then replied, “Monks, they called me son because I was a son or a nephew to each of them for one thousand five hundred existences in the past.” The Buddha continued to stay there, near the brāhmin couple, for three more months and during that time, both the brāhmin and his wife attained arahatship, and then realized parinibbāna. The monks, now knowing that the brāhmin couple had already become arahats, asked the Buddha where they were reborn. To them the Buddha answered: “Those who have become arahats are not reborn anywhere; they have realized Nibbāna.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 225)

ye munayo ahiṃsakā niccaṃ kāyena saṃvutā

te yattha gantvā na socare accutaṃ ṭhānaṃ yanti

ye munayo [munaya]: those sages; ahiṃsakā: (are) harmless; niccaṃ [nicca]: constantly; kāyena saṃvutā: restrained in body; te: they; yattha: to some place; gantvā: gone; na socare: do not grieve; accutaṃ ṭhānaṃ [ṭhāna]: that deathless place; yanti: reach

Those harmless sages, perpetually restrained in body, reach the place of deathlessness, where they do not grieve.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 225)

accutaṃ ṭhānaṃ: the unchanging place. This is yet another definition of Nibbāna–the deathless. Everything changes–but this rule does not apply to Nibbāna. In contra-distinction to saṃsāra, the phenomenal existence, Nibbāna is eternal (dhuva), desirable (subha), and happy (sukha).

According to Buddhism all things, mundane and supramundane, are classified into two divisions, namely, those conditioned by causes (samkhata) and those not conditioned by any cause (asamkhata). “These three are the features of all conditioned things (samkhatalakkhanāni): arising (uppāda), cessation (vaya), and change of state (thitassa aññataṭṭam).” Arising or becoming is an essential characteristic of everything that is conditioned by a cause or causes. That which arises or becomes is subject to change and dissolution. Every conditioned thing is constantly becoming and is perpetually changing. The universal law of change applies to everything in the cosmos–both mental and physical–ranging from the minutest germ or tiniest particle to the highest being or the most massive object. Mind, though imperceptible, changes faster even than matter.

Nibbāna, a supramundane state, realized by Buddhas and arahats, is declared to be not conditioned by any cause. Hence it is not subject to any becoming, change and dissolution. It is birthless (ajāta), decayless (ajara), and deathless (amara). Strictly speaking, Nibbāna is neither a cause nor an effect. Hence it is unique (kevala). Everything that has sprung from a cause must inevitably pass away, and as such, is undesirable (asubha).

Life is man’s dearest possession, but when he is confronted with insuperable difficulties and unbearable burdens, then that very life becomes an intolerable burden. Sometimes, he tries to seek relief by putting an end to his life as if suicide would solve all his individual problems. Bodies are adorned and adored. But those charming, adorable and enticing forms, when disfigured by time and disease, become extremely repulsive. Men desire to live peacefully and happily with their near ones, surrounded by amusements and pleasures, but, if by some misfortune, the wicked world runs counter to their ambitions and desires, the inevitable sorrow is then almost indescribably sharp.

The following beautiful parable aptly illustrates the fleeting nature of life and its alluring pleasures. A man was forcing his way through a thick forest beset with thorns and stones. Suddenly, to his great consternation, an elephant appeared and gave chase. He took to his heels through fear, and, seeing a well, he ran to hide in it. But to his horror, he saw a viper at the bottom of the well. However, lacking other means of escape, he jumped into the well, and clung to a thorny creeper that was growing in it. Looking up, he saw two mice, a white one and a black one, gnawing at the creeper. Over his face there was a beehive from which occasional drops of honey trickled. This man, foolishly unmindful of this precarious position, was greedily tasting the honey. A kind person volunteered to show him a path of escape. But the greedy man begged to be excused’till he had enjoyed himself.

The thorny path is saṃsāra, the ocean of life. It is beset with difficulties and obstacles to overcome, with opposition and unjust criticism, with attacks and insults to be borne. Such is the thorny path of life. The elephant here resembles death; the viper, old age; the creeper, birth; the two mice, night and day. The drops of honey correspond to the fleeting sensual pleasures. The man represents the so-called being. The kind person represents the Buddha. The temporary material happiness is merely the gratification of some desire. When the desired thing is gained, another desire arises. Insatiate are all desires. Sorrow is essential to life, and cannot be evaded. Nibbāna, being non-conditioned, is eternal, (dhuva), desirable (subha), and happy (sukha). The happiness of Nibbāna should be differentiated from ordinary worldly happiness. Nibbāna bliss grows neither stale nor monotonous. It is a form of happiness that never wearies, never fluctuates. It arises by allaying passions (vūpasama) unlike that temporary worldly happiness which results from the gratification of some desire (vedayita).