Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 213:

pemato jāyatī soko pemato jāyatī bhayaṃ |

pemato vippamuttassa natthi soko kuto bhayaṃ || 213 ||

213. From affection grief is born, from affection fear, one who is affection-free has no grief—how fear?

The Story of Visākhā

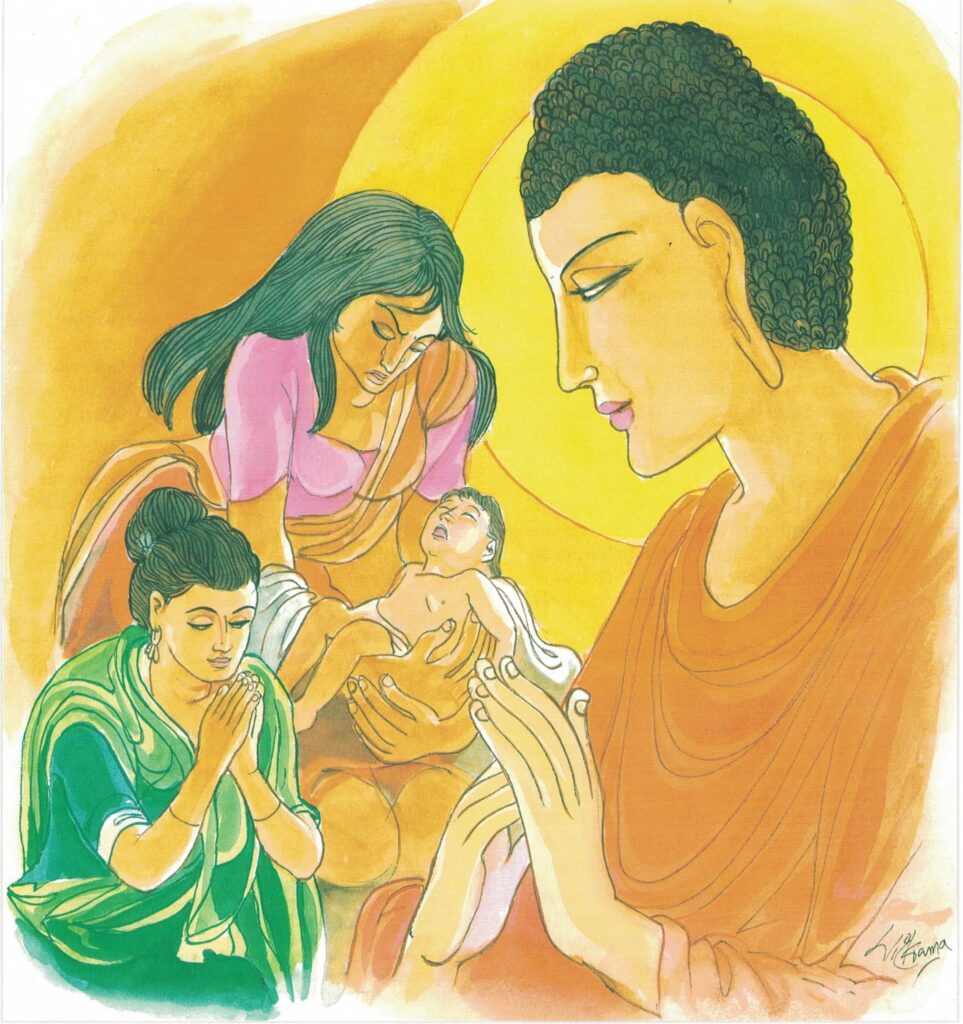

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse with reference to Visākhā, the renowned donor of the Pubbārāma Monastery. The story goes that Visākhā used to permit her son’s daughter, a maiden named Dattā, to minister to the monks in her house when she was absent. After a time Dattā died. Visākhā attended to the deposition of her body, and then, unable to control her grief, went sad and sorrowful to the Buddha, and having saluted Him, sat down respectfully on one side. Said the Buddha to Visākhā, “Why is it, Visākhā, that you sit here sad and sorrowful, with tears in your eyes, weeping and wailing?”

Visākhā then explained the matter to the Buddha, saying, “Venerable, the girl was very dear to me and she was faithful and true; I shall not see the likes of her again.” “But, Visākhā, how many inhabitants are there in Sāvatthi?” “I have heard you say, Venerable, that there are seventy million.” “But suppose all these persons were as dear to you as was Dattā; would you like to have it so?” “Yes, Venerable.” “But how many persons die every day in Sāvatthi?” “A great many, Venerable.” “In that case it is certain that you would lack time to satisfy your grief, you would go about both by night and by day, doing nothing but wail.” “Certainly, Venerable; I quite understand.” Then said the Buddha, “Very well, do not grieve. For whether it be grief or fear, it springs solely from affection.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 213)

pemato soko jāyatī pemato bhayaṃ jāyatī

pemato vippamuttassa soko natthi bhayaṃ kuto?

pemato [pemata]: because of affection; soko: sorrow; jāyatī: is born; pemato [pemata]: because of affection; bhayaṃ [bhaya]: fear, jāyatī: arises; pemato vippamuttassa: to one free of affection; soko natthi: there is no sorrow; bhayaṃ [bhaya]: fear; kuto: how can there be?

From affection arises sorrow. From affection fear arises. To one free of affection there is no sorrow. Therefore, how can there be fear for such a person?

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 213)

Visākhā’s grief: The Buddha spoke this verse to pacify Visākhā, the greatest female lay supporter of the Buddha in the early days of Buddhasāsana (The Dispensation of the Buddha). Visākhā’s life is intimately interwoven with the early history of Buddhism. There is an incident in her life which reveals her dutiful kindness even towards animals. Hearing that her well-bred mare gave birth to a foal in the middle of the night, she immediately repaired to the stable with her female attendants bearing torches in their hands, and attended to all the mare’s needs with the greatest care and attention.

As her father-in-law was a staunch follower of Nigaṇṭhanātaputta, he invited a large number of naked ascetics to his house for alms. On their arrival Visākhā was requested to come and render homage to these so-called arahats. She was delighted to hear the word arahat and hurried to the hall only to see naked ascetics devoid of all modesty. The sight was too unbearable for a refined lady like Visākhā. She reproached her father-in-law and retired to her quarters without entertaining them. The naked ascetics took offence and found fault with the millionaire for having brought a female follower of the ascetic Gotama to his house. They asked him to expel her from the house immediately. The millionaire pacified them. One day he sat on a costly seat and began to eat some sweet milk rice-porridge from a golden bowl. At that moment a monk entered the house for alms. Visākhā was fanning her father-in-law and without informing him of his presence she moved aside so that he might see him. Although he saw him he continued eating as if he had not seen him.

Visākhā politely told the monk, “Pass on, Venerable, my father-in-law is eating stale fare (purānam).” The ignorant millionaire misconstruing her words, was so provoked that he ordered the bowl to be removed and Visākhā to be expelled from the house. Visākhā was the favourite of all the inmates of the house, and so nobody dared to touch her. But Visākhā, disciplined as she was, would not accept without protest such treatment even from her father-in-law. She politely said, “Father, this is no sufficient reason why I should leave your house. I was not brought here by you like a slave girl from some ford. Daughters whose parents are alive do not leave like this. It is for this very reason that my father, when I set out to come here, summoned eight clansmen and entrusted me to them, saying, ‘If there be any fault in my daughter, investigate it.’ Send word to them and let them investigate my guilt or innocence.”

The millionaire agreed to her reasonable proposal and summoning them, said, “At a time of festivity, while I was sitting and eating sweet milk rice-porridge from a golden bowl, this girl said that what I was eating was unclean. Convict her of this fault and expel her from the house.” Visākhā proved her innocence stating, “That is not precisely what I said. When a certain Monk was standing at the door for alms, my father-in-law was eating sweet milk rice-porridge, ignoring him. Thinking to myself that my father, without performing any good deed in this life, is only consuming the merits of past deeds, I told the Monk, ‘Pass on, Venerable, my father-in-law is eating stale fare.’ What fault of mine is there in this?”

She was acquitted of the charge, and the father-in-law himself agreed she was not guilty. But the spiteful millionaire charged her again for having gone behind the house with male and female attendants in the middle watch of the night. When she explained that she actually did so in order to attend on a mare in travail, the clansmen remarked that their noble daughter had done an exemplary act which even a slave-girl would not do. She was thus acquitted of the second charge too. But the revengeful millionaire would not rest until she was found guilty. Next time he found fault with her for no reason. He said that before her departure from home her father gave her ten admonitions. For instance, he said to her, “The indoor fire is not to be taken out of doors. Is it really possible to live without giving fire even to our neighbours on both sides of us?” questioned the millionaire.

She availed herself of the opportunity to explain all the ten admonitions in detail to his entire satisfaction. The millionaire was silenced and he had no other charges to make. Having proved her innocence, self-respecting Visākhā now desired to leave the house as she was ordered to do so in the first place. The millionaire’s attitude towards Visākhā was completely changed, and he was compelled to seek pardon from her daughter-in-law for what he had uttered through ignorance.