Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 212:

piyato jāyatī soko piyato jāyatī bhayaṃ |

piyato vippamuttassa natthi soko kuto bhayaṃ || 212 ||

212. From endearment grief is born, from endearment fear, one who is endearment-free has no grief—how fear?

The Story of a Rich Householder

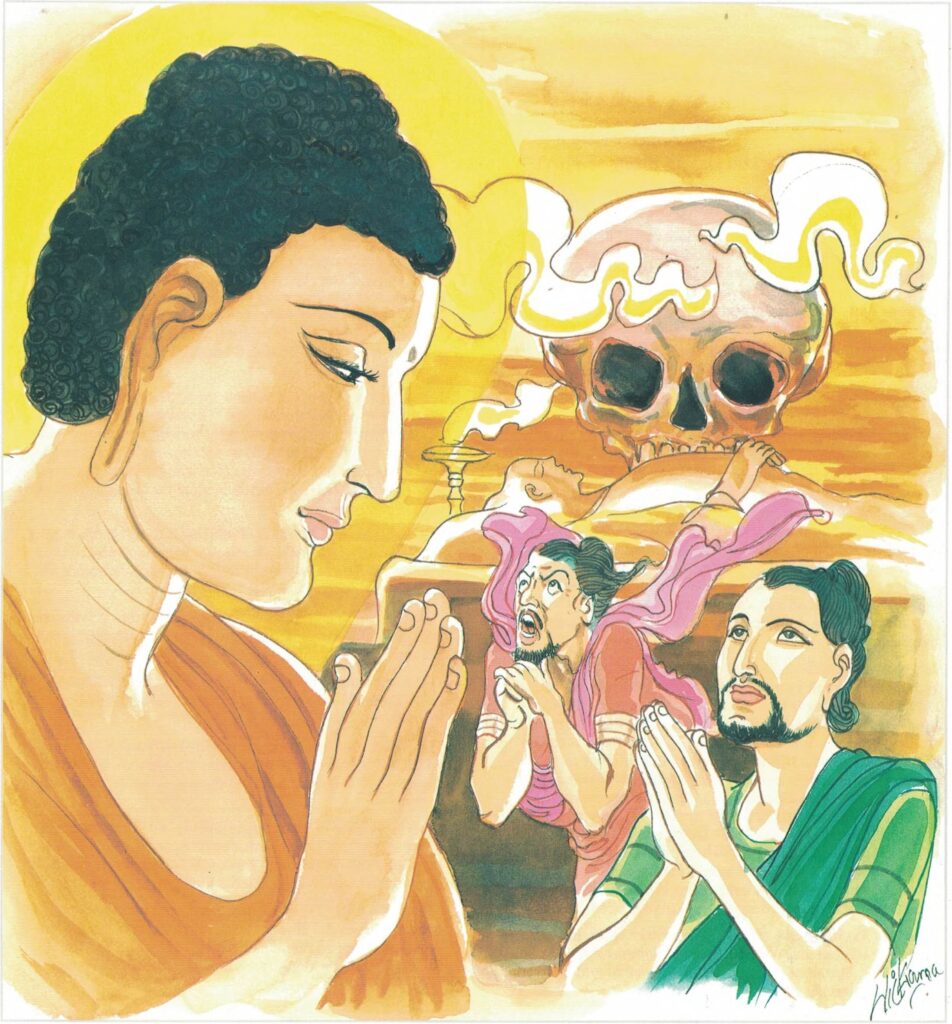

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse with reference to a rich householder who had lost his son.

The story goes that this layman, on losing his son, was so overwhelmed with grief that he went every day to the burning ground and wept, being unable to restrain his grief. As the Buddha surveyed the world at dawn, he saw that the layman had the faculties requisite for conversion. So when he came back from his alms-round, he took one attendant monk and went to the layman’s door. When the layman heard that the Buddha had come to his house, he thought to himself, “He must wish to exchange the usual compliments of health and civility with me.” So he invited the Buddha into his house, provided him with a seat in the house-court, and when the Buddha had taken his seat, approached him, saluted him, and sat down respectfully on one side.

At once the Buddha asked him, “Layman, why are you sad?” “I have lost my son;therefore I am sad,” replied the layman. Said the Buddha, “Grieve not, layman. That which is called death is not confined to one place or to one person, but is common to all creatures who are born into this world. Not one of the elements of being is permanent. Therefore one should not give himself up to sorrow, but should rather take a reasonable view of death, even as it is said, ‘Mortality has suffered mortality, dissolution has suffered dissolution.’

“For wise men of old sorrowed not over the death of a son, but applied themselves diligently to meditation upon death, saying to themselves, ‘Mortality has suffered mortality, dissolution has suffered dissolution.’ In times past, wise men did not do as you are doing on the death of a son. You have abandoned your wonted occupations, have deprived yourself of food, and spend your time in lamentation. Wise men of old did not do so. On the contrary, they applied themselves diligently to meditation upon death, would not allow themselves to grieve, ate their food as usual, and attended to their wonted occupations. Therefore grieve not at the thought that your dear son is dead. For whether sorrow or fear arises, it arises solely because of one that is dear.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 212)

piyato soko jāyatī piyato bhayaṃ jāyatī piyato

vippamuttassa soko natthi bhayaṃ kuto

piyato [piyata]: because of endearment; soko: sorrow; jāyatī: is born; piyato [piyata]: because of endearment; bhayaṃ [bhaya]: fear; jāyatī: arises; piyato vippamuttassa: to one free of endearment; soko natthi: there is no sorrow; bhayaṃ [bhaya]: fear; kuto: how can there be?

From endearment arises sorrow. From endearment fear arises. For one free of endearment, there is no sorrow. Therefore how can there be fear for such a person?

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 212)

The Buddha’s daily routine: According to the story that gave rise to this stanza and to many others, the Buddha, each morning, contemplates the world, looking for those who should be helped. The Buddha can be considered the most energetic and the most active of all religious teachers that ever lived on earth. The whole day He was occupied with His religious activities, except when He was attending to His physical needs. He was methodical and systematic in the performance of His daily duties. His inner life was one of meditation and was concerned with the experiencing of Nibbanic Bliss, while His outer life was one of selfless service for the moral upliftment of the world. Himself enlightened, He endeavoured His best to enlighten others and liberate them from the ills of life.

His day was divided into five parts, namely,

- The forenoon session,

- The afternoon session,

- The first watch,

- The middle watch and

- The last watch.

Usually, early in the morning, He surveys the world with His divine eye to see whom he could help. If any person needs His spiritual assistance, uninvited He goes, often on foot, sometimes by air using His psychic powers, and converts that person to the right path. As a rule He goes in search of the vicious and the impure, but the pure and the virtuous come in search of Him. For instance, the Buddha went of His own accord to convert the robber and murderer Angulimāla and the wicked demon Ālavaka, but pious young Visākhā, generous millionaire Anāthapiṇḍika, and intellectual Sāriputta and Moggallāna came to Him for spiritual guidance. While rendering such spiritual service to whomsoever it is necessary, if He is not invited for alms-giving by a lay supporter at some particular place, He, before whom kings prostrated themselves, would go in quest of alms through alleys and streets, with bowl in hand, either alone or with His disciples. Standing silently at the door of each house, without uttering a word, He collects whatever food is offered and placed in the bowl and returns to the monastery. Even in His eightieth year when He was old and in indifferent health, He went on His rounds for alms in Vesāli. Before midday He finishes His meals. Immediately after lunch He daily delivers a short discourse to the people, establishes them in the Three Refuges and the Five Precepts and if any person is spiritually advanced, he is shown the path to sainthood. At times He grants ordination to them if they seek admission to the Sangha, and then retires to His chamber.