Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 195-196:

pūjārahe pūjayato buddhe yadi va sāvake |

papañca samatikkante tiṇṇa sokapariddave || 195 ||

te tādise pūjayato nibbute akutobhaye |

na sakkā puññaṃ saṅkhātuṃ im’ettam’iti kena ci || 196 ||

195. Who venerates the venerable—the Buddhas or their hearkeners who’ve overcome the manifold, grief and lamentation left…

196. …They who are ‘Thus’, venerable, cool and free from every fear—no one is able to calculate their merit as ‘just-so-much’.

The Story of the Golden Stūpa of Kassapa Buddha

While travelling from Sāvatthi to Vārānasi, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to a brāhmin and the Golden Stūpa of Kassapa.

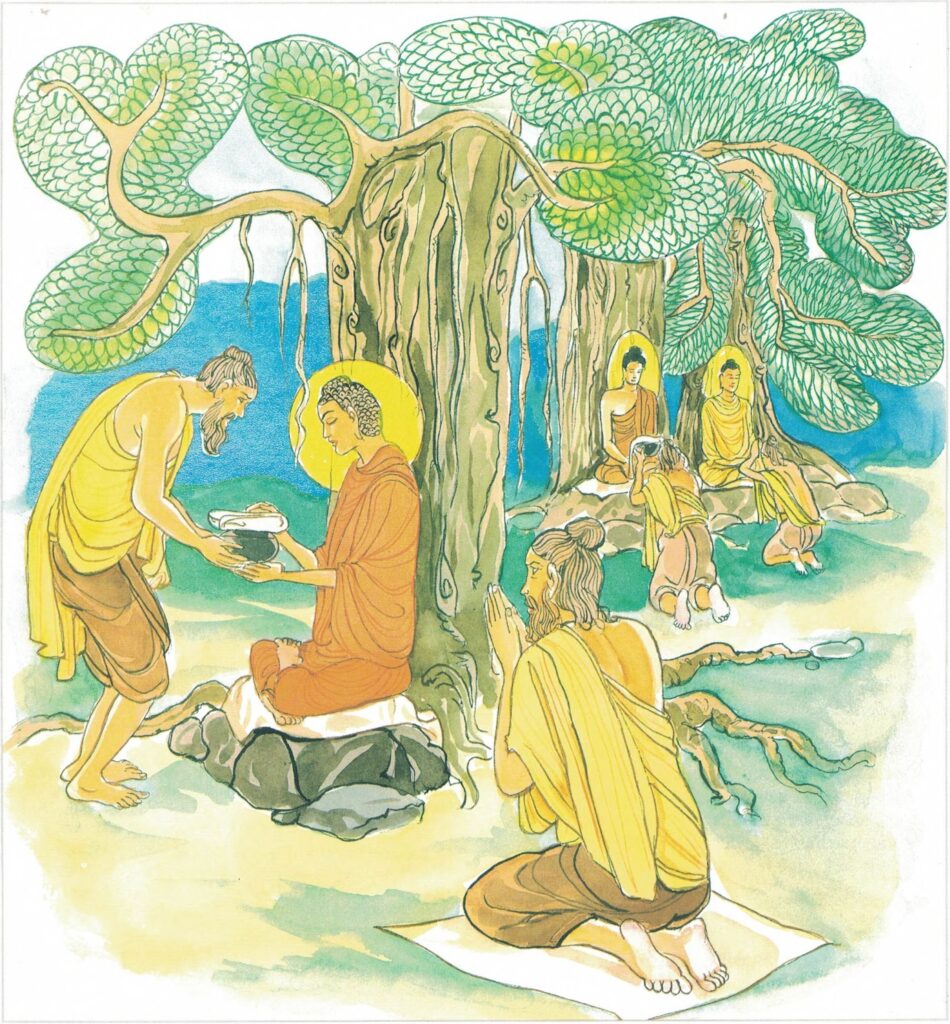

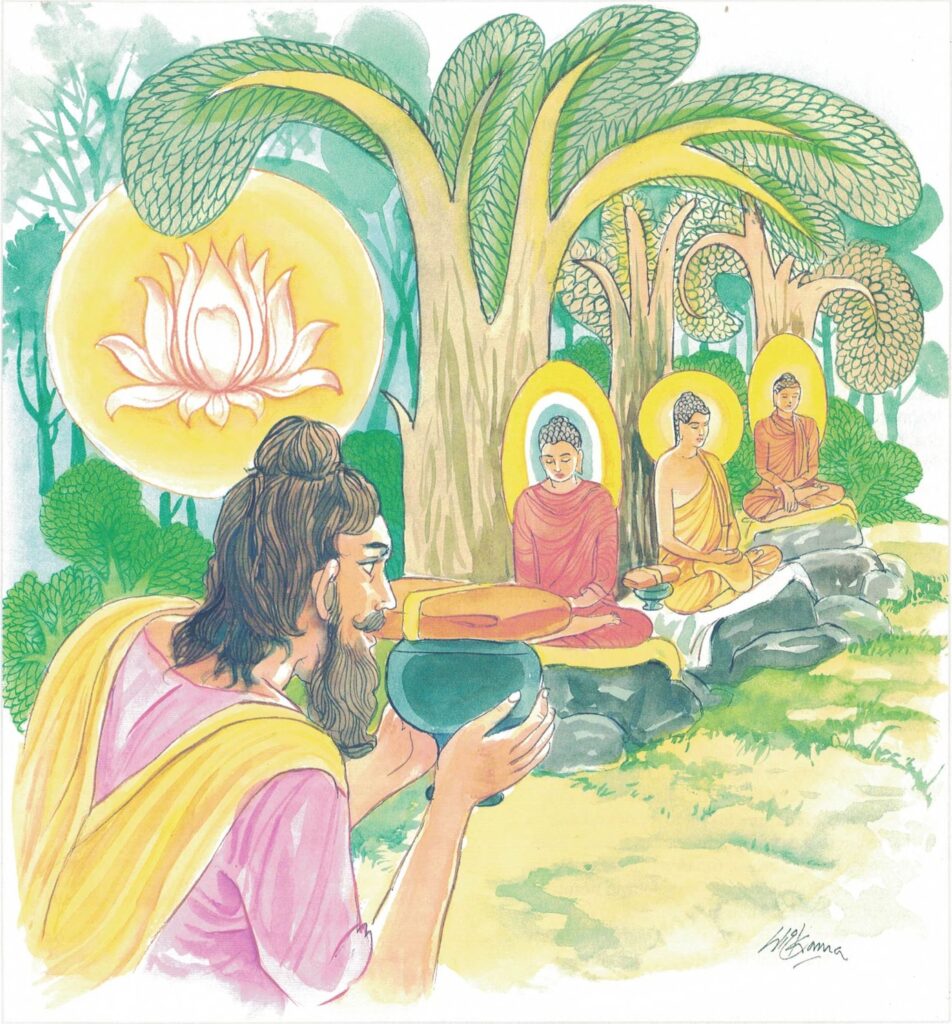

One day Buddha departed from Sāvatthi, accompanied by a large company of monks and set out for Vārānasi. On his way thither he came to a certain shrine near the village Todeyya. There the Buddha sat down, sent forth Ānanda and bade him to summon a brāhmin who was tilling the soil nearby. When the brāhmin came, he omitted to pay reverence to the Buddha, but paid reverence only to the shrine. Having so done, he stood there before the Buddha. The Buddha said, “How do you regard this place, brāhmin?” The brāhmin replied, “This shrine has come down to us through generations, and that is why I reverence it, Venerable Gotama.” Thereupon the Buddha praised him, saying, “In reverencing this place you have done well, brāhmin.”

When the monks heard this, they entertained misgivings and said, “For what reason did you bestow this praise?” So in order to dispel their doubts, the Buddha recited the Ghatīkāra Suttanta in the Majjhima Nikāya. Then by the superhuman power, He created in the air a mountain of gold double the golden shrine of the Buddha Kassapa, a league in height. Then, pointing to the numerous company of His disciples, He said, “Brāhmin, it is even more fitting to render honour to men who are so deserving of honour as these.” Then, in the words of the Sutta of the Great Decease, He declared that the Buddhas and others, four in number, are worthy of shrines. Then He described in detail the three kinds of shrines: the shrine for bodily relics, the shrine for commemorative relics, and the shrine for articles used or enjoyed. At the conclusion of the lesson the brāhmin attained the fruit of conversion.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 195)

papañca samatikkante tiṇṇa sokapariddave

pūjārahe Buddhe yadi vā sāvake pūjayato

papañca samatikkante: those who have gone beyond ordinary apperception; tiṇṇa sokapariddave: who have crossed over grief and lamentation; pūjārahe: who deserve to be worshipped; Buddhe: (namely) the Buddha; yadi vā: and also: sāvake: the disciples of the Buddha; pūjayato [pūjayata]: if someone were to worship them

Those who have gone beyond apperception (the normal way of perceiving the world), who have crossed over grief and lamentation. They deserve to be worshipped; namely, the Buddhas and their disciples.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 196)

nibbute akutobhaye tādise te pūjayato puññaṃ

imaṃ mattaṃ iti saṅkhātuṃ kena ci api na sakkā

nibbute: who have reached imperturbability; akutobhaye: who does to tremble or fear; tādise: that kind of being; te pūjayato [pūjayata]: one who reveres; puññaṃ [puñña]: merit; imaṃ mattaṃ iti: as this much or so much; saṅkhātuṃ [saṅkhātu]: to quantify; na sakkā: not able; kenaci: by anyone

One who worships those who have attained imperturbability and do not tremble or fear, earns much merit. The merit earned by such a person cannot be measured by anyone.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 195-196)

pūjāraho pūjayato, Buddhe yadiva sāvake: worship those who deserved to be worshipped, the Buddhas and their disciples. Why is the Buddha to be worshipped? His attainment of Enlightenment and his mission will elucidate it. The Buddha lived in Jambudīpa over 2,500 years ago, and was known as Siddhattha (in Sanskrit Siddhārtha, the one whose purpose has been achieved). Gotama (in Sanskrit Gautama) was his family name. His father, Suddhodana, ruled over the land of the Sākyas at Kapilavatthu on the Nepalese frontier. Mahāmāyā, princess of the Koliyas, was Suddhodana’s queen.

On the full-moon day of May–vasanta-tide, when in Jambudīpa the trees were laden with leaf, flower, and fruit–and man, bird and beast were in joyous mood, Queen Mahāmāyā was travelling in state from Kapilavatthu to Devadaha, her parental home, according to the custom of the times, to give birth to her child. But that was not to be, for halfway between the two cities, in the Lumbini Grove, under the shade of a flowering Sal tree, she brought forth a son.

Queen Mahāmāyā, the mother, passed away on the seventh day after the birth of her child, and the baby was nursed by his mother’s sister, Pajāpati Gotami. The child was nurtured till manhood, in refinement, amidst an abundance of luxury. The father did not fail to give his son the education that a prince ought to receive. He became skilled in many a branch of knowledge, and in the arts of war and he easily excelled all others. Nevertheless, from his childhood, the prince was given to serious contemplation. When the prince grew up the father’s fervent wish was that his son should marry, bring up a family and be his worthy successor; but he feared that the prince would one day give up home for the homeless life of an ascetic.

According to the custom of the time, at the early age of sixteen, the prince was married to his cousin Yasodharā, the only daughter of King Suppabuddha and Queen Pamitā of the Koliyas. The princess was of the same age as the prince. Lacking nothing of the material joys of life, he lived without knowing of sorrow. Yet all the efforts of the father to hold his son a prisoner to the senses and make him worldly-minded were of no avail. King Suddhodana’s endeavours to keep life’s miseries from his son’s inquiring eyes only heightened Prince Siddhattha’s curiosity and his resolute search for Truth and Enlightenment.

With the advance of age and maturity, the prince began to glimpse the problems of the world. As it was said, he saw four visions: the first was a man weakened with age, utterly helpless; the second was the sight of a man who was mere skin and bones, supremely unhappy and forlorn, smitten with some disease; the third was the sight of a band of lamenting kinsmen bearing on their shoulders the corpse of one beloved, for cremation. These woeful signs deeply moved him. The fourth vision, however, made a lasting impression. He saw a recluse, calm and serene, aloof and independent, and learnt that he was one who had abandoned his home to live a life of purity, to seek Truth and solve the riddle of life. Thoughts of renunciation flashed through the prince’s mind and in deep contemplation he turned homeward. The heart-throb of an agonized and ailing humanity found a responsive echo in his own heart. The more he came in contact with the world outside his palace walls, the more convinced he became that the world was lacking in true happiness.

In the silence of that moonlit night (it was the full-moon of July) such thoughts as these arose in him: “Youth, the prince of life, ends in old age and man’s senses fail him when they are most needed. The healthy and hearty lose their vigour when disease suddenly creeps in. Finally, death comes, sudden perhaps and unexpected, and puts an end to this brief span of life. Surely, there must be an escape from this unsatisfactoriness, from ageing and death.” Thus the great intoxication of youth, of health, and of life left him. Having seen the vanity and the danger of the three intoxications, he was overcome by a powerful urge to seek and win the Deathless, to strive for deliverance from old age, illness and misery to seek it for himself and for all beings that suffer. It was his deep compassion that led him to the quest ending in Enlightenment, in Buddhahood. It was compassion that now moved his heart towards the renunciation and opened for him the doors of the supreme cage of his home life. It was compassion that made his determination unshakable even by the last parting glance at his beloved wife, asleep with their baby in her arms. Now at the age of twenty-nine, in the flower of youthful manhood, on the day his beautiful Yasodharā gave birth to his only son, Rāhula, who made the parting more sorrowful, he tore himself away. The prince, with a superhuman effort of will, renounced wife, child, father and the crown that held the promise of power and glory. In the guise of an indigent ascetic, he retreated into forest solitude, to seek the eternal verities of life, in quest of the supreme security from bondage–Nibbāna. Dedicating himself to the noble task of discovering a remedy for life’s universal ill, he sought guidance from two famous sages, Alāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta, hoping that they, being masters of meditation, would show him the way to deliverance. He practiced mental stillness and reached the highest meditative attainments possible thereby, but was not satisfied with anything short of enlightenment. Their range of knowledge, mystical experience, however, was insufficient to grant him what he earnestly sought. He, therefore, left them in search of the unknown truth. In his wanderings he finally reached Uruvela, by the river Nerañjarā at Gayā. He was attracted by its quiet and dense groves and the clear waters of the river. Finding that this was a suitable place to continue his quest for enlightenment, he decided to stay. Five other ascetics who admired his determined effort waited on him. They were Koṇḍañña, Bhaddiya, Vappa, Mahānāma and Assaji.

There was, and still is, a belief in Jambudīpa among many of her ascetics that purification and final deliverance from ills can be achieved by rigorous self-mortification, and the ascetic Gotama decided to test the truth of it. And so there at Uruvela he began a determined struggle to subdue his body, in the hope that his mind, set free from the physical body, might be able to soar to the heights of liberation. Most zealous was he in these practices. He lived on leaves and roots, on a steadily reduced pittance of food, he wore rags, he slept among corpses or on beds of thorns. He said, “Rigorous have I been in my ascetic discipline. Rigorous have I been beyond all others. Like wasted, withered reeds became all my limbs.” In such words as these, in later years, having attained to full enlightenment, did the Buddha give an awe-inspiring description of his early penances. Struggling thus, for six long years, he came nearly to death, but he found himself still away from his goal. The utter futility of self-mortification became abundantly clear to him, by his own experience; his experiment with self mortification, for enlightenment, had failed. But undiscouraged, his still active mind searched for new paths to the aspired-for goal. Then it happened that he remembered the peace of his meditation in childhood, under a roseapple tree, and he confidently felt: “This is the path to enlightenment.” He knew, however, that, with a body so utterly weakened as his, he could not follow that path with any chance of success. Thus he abandoned self-mortification and extreme fasting and took normal food. His emaciated body recovered its former health and his exhausted vigour soon returned. Now his five companions left him in their disappointment; for they thought that he had given up the effort, to live a life of abundance instead.

Nevertheless with firm determination and complete faith in his own purity and strength, unaided by any teacher, accompanied by none, the Bodhisatta (as he was known before he attained enlightenment) resolved to make his final search in complete solitude. Cross-legged he sat under a tree, which later became known as the Bodhi-tree, the Tree of Enlightenment or Tree of Wisdom, on the bank of Nerañjarā River, at Gayā (now known as Buddha-Gayā)–at “a pleasant spot soothing to the senses and stimulating to the mind” making the final effort with the inflexible resolution: “Though only my skin, sinews, and bones remain, and my blood and flesh dry up and wither away, yet will I never stir from this seat until I have attained full enlightenment (sammāsambodhi).” So indefatigable in effort as he was, and so resolute to realize Truth and attain Full Enlightenment that he applied himself to the mindful in-and-out breathing (āna + apāna sati), the meditation he had developed in his childhood, and the Bodhisatta entered upon and dwelt in the first degree of meditative mental repose (jhāna; sanskrit, dhyāna).