Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 183-185:

sabbapāpassa akaraṇaṃ kusalassa upasampadā |

sacittapariyodapanaṃ etaṃ buddhāna’sāsanaṃ || 183 ||

khantī paramaṃ tapo titikkhā nibbāṇaṃ paramaṃ vadanti buddhā |

na hi pabbajito parūpaghātī samaṇo hoti paraṃ viheṭhayanto || 184 ||

anūpavādo anūpaghāto pātimokkhe ca saṃvaro |

mattaññutā ca bhattasmiṃ pantaṃ’ca sayanāsanaṃ |

adhicitte ca āyogo etaṃ buddhāna’sāsanaṃ || 185 ||

183. Every evil never doing and in wholesomeness increasing and one’s heart well-purifying: this is the Buddha’s Teaching.

184. Patience is the austerity supreme, Buddhā Nibbana’s supreme the Buddhas say. One who irks or others harms is not ordained or monk becomes.

185. Not reviling, neither harming, restrained to limit ‘freedom’s’ ways, knowing reason in one’s food, dwelling far in solitude, and striving in the mind sublime: this is the Buddha’s Teaching.

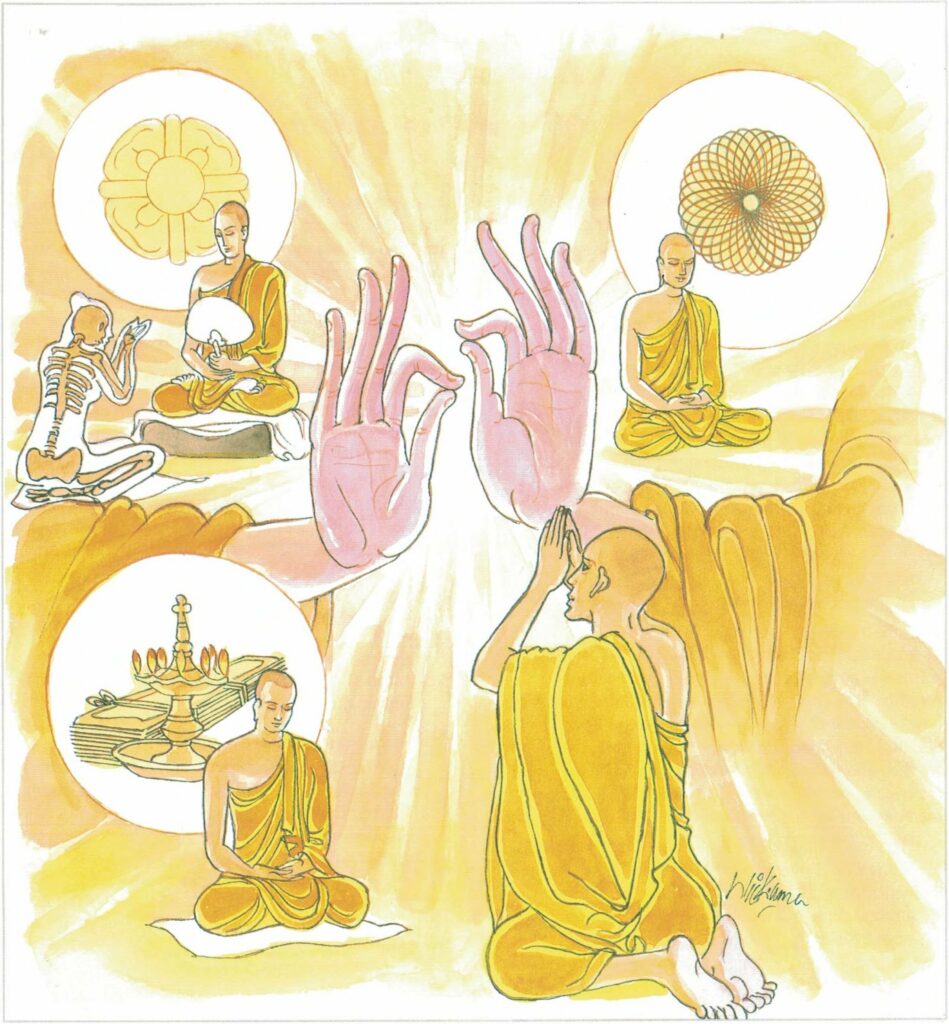

The Story of the Question Raised by Venerable Ānanda

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to the question raised by Venerable Ānanda regarding fundamental instructions to monks by the previous Buddhas.

We are told that as the Venerable sat in his day-quarters, he thought to himself, “The Buddha has described the mothers and fathers of the seven Buddhas, their length of life, the tree under which they got enlightenment, their company of disciples, their chief disciples, and their principal supporter. All this the Buddha has described. But he has said nothing about their mode of observance of a day of fasting the same as now, or was it different?” Accordingly he approached the Buddha and asked him about the matter.

Now in the case of these Buddhas, while there was a difference of time, there was no difference in the stanzas they employed. The supremely enlightened Vipassi kept fast-day every seven years, but the admonition he gave in one day sufficed for seven years. Sikhī and Vessabhū kept fast-day every six years; Kakusandha and Konāgamana, every year; Kassapa, Possessor of the ten forces, kept fast-day every six months, but the admonition of the latter sufficed for six months. For this reason the Buddha, after explaining to the Venerable this difference of time, explained that their observance of a fast-day was the same in every case.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 183)

sabbapāpassa akaraṇaṃ kusalassa upasampadā

sacitta pariyodapanaṃ etaṃ Buddhāna sāsanaṃ

sabbapāpassa: from all evil actions; akaraṇaṃ [akaraṇa]: refraining; kusalassa: wholesome actions; upasampadā: generation and maintenance; sacitta pariyodapanaṃ [pariyodapana]: purifying and disciplining one’s own mind; etaṃ: this is; Buddhānaṃ [Buddhāna]: of the Buddhas; sāsanaṃ [sāsana]: teaching.

Abandoning all evil,–entering the state of goodness, and purifying one’s own mind by oneself–this is the Teaching of the Buddha.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 184)

titikkhā khantī paramaṃ tapo, buddhā nibbāṇaṃ paramaṃ vadanti,

parūpaghātī pabbajito na hi hoti paraṃ viheṭhayanto samaṇo na hi hoti

titikkhā: enduring; khantī: patience; paramaṃ tapo: (is the) highest asceticism; Buddhā: the Buddhas; nibbāṇaṃ [nibbāṇa]: the imperturbability; paramaṃ [parama]: (is) supreme; vadanti: state; parūpaghātī: hurting others; pabbajito [pabbajita]: a renunciate; na hi hoti: is certainly not; paraṃ viheṭhayanto [viheṭhayanta]: one who harms others; samaṇo na hoti: is certainly not a monk

Enduring patience is the highest asceticism. The Buddhas say that imperturbability (Nibbāna) is the most supreme. One is not a renunciate if he hurts another. Only one who does not harm others is a true saint (samana).

Explanatory Translation (Verse 185)

anūpavādo anūpaghāto pātimokkhe saṃvaro ca

bhattasmiṃ mattññutā ca panthaṃ sayanāsanaṃ ca

adhicitte āyogo ca etaṃ Buddhāna sāsanaṃ

anūpavādo [anūpavāda]: not finding fault with others; anūpaghāto [anūpaghāta]: refraining from harassing others; pātimokkhe: in the main forms of discipline; saṃvaro [saṃvara]: well restrained; ca bhattasmiṃ [bhattasmi]: in food; mattññutā: moderate; ca panthaṃ sayanāsanaṃ [sayanāsana]: also taking delight in solitary places (distanced from human settlement); adhicitte ca: also in higher meditation; āyogo [āyoga]: (and in) constant practice; etaṃ: all this; Buddhānaṃ [Buddhāna]: of the Buddhas’; sāsanaṃ [sāsana]: (is) the teaching

To refrain from finding fault with others, to refrain from hurting others, to be trained in the highest forms of discipline and conduct; to be moderate in eating food; to take delight in solitude; and to engage in higher thought (which is meditation).

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 183-185)

Sabbapāpassa akaranaṃ: The religion of the Buddha is summarised in this verse.

What is associated with the three immoral roots of attachment (lobha), ill-will (dosa), and delusion (moha) is evil. What is associated with the three moral roots of generosity (alobha), goodwill or loving-kindness (adosa), and wisdom (amoha) is good.

Pabbajito: one who casts aside his impurities, and has left the world.

Samaṇo: one who has subdued his passions, an ascetic.

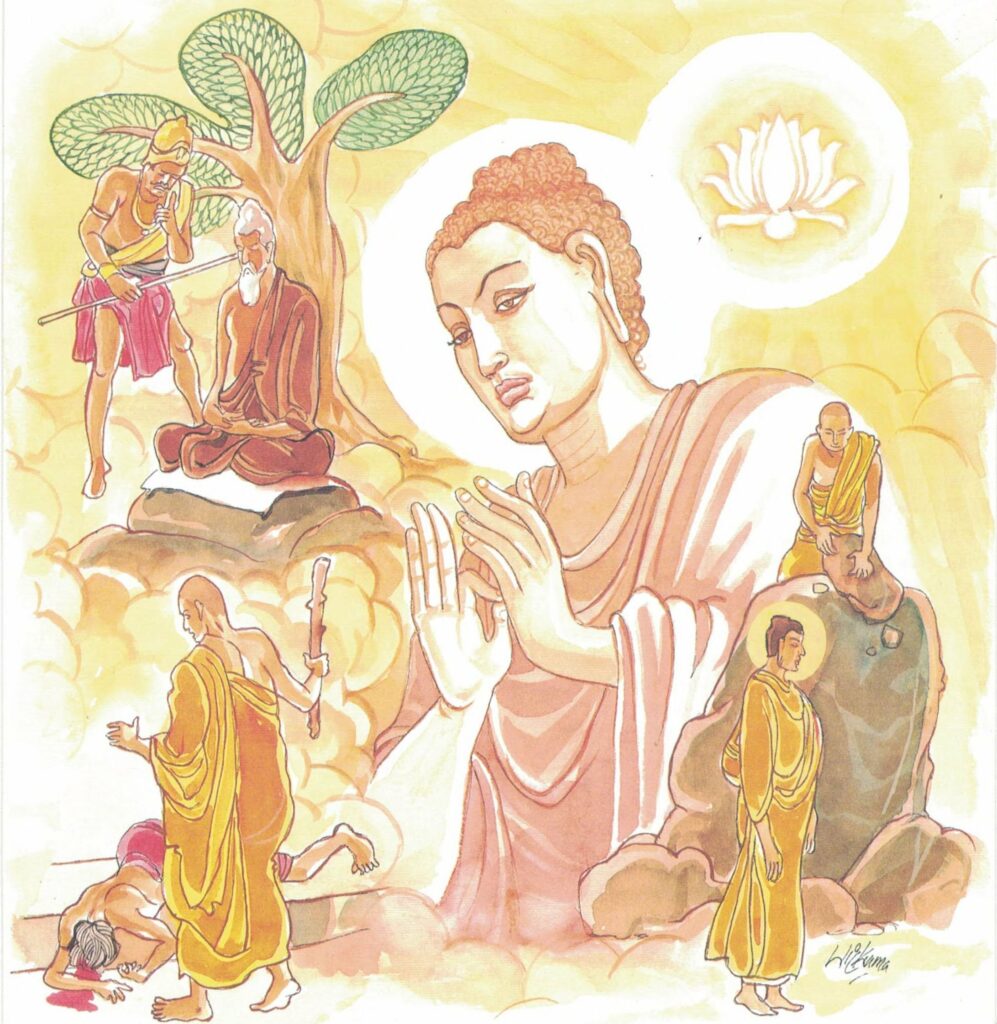

khantī paramaṃ tapo: patience is the highest austerity. It is the patient endurance of suffering inflicted upon oneself by others, and the forbearance of others’ wrongs. A Bodhisatta practises patience to such an extent that he is not provoked even when his hands and feet are cut off. In the Khantivādi Jātaka, it appears that not only did the Bodhisatta cheerfully endure the tortures inflicted by the drunkard king, who mercilessly ordered his hands and feet, nose and ears to be cut off, but requited those injuries with a blessing. Lying on the ground, in a deep pool of His own blood, with mutilated limbs, the Bodhisatta said, “Long live the king, who cruelly cut my body thus.” Pure souls like mine such deeds as these with anger ne’er regard.”

Of his forbearance it is said that whenever he is harmed he thinks of the aggressor–‘This person is a fellow-being of mine. Intentionally or unintentionally I myself must have been the source of provocation, or it may be due to a past evil kamma of mine. As it is the outcome of my own action, why should I harbour ill-will towards him?’

It may be mentioned that a Bodhisatta is not irritated by any man’s shameless conduct either. Admonishing His disciples to practise forbearance, the Buddha said in the Kakacūpama Sutta–“Though robbers, who are highway men, should sever your limbs with a two-handled saw yet if you thereby defile your mind, you would be no follower of my teaching. Thus should you train yourselves: Unsullied shall our hearts remain. No evil word shall escape our lips. Kind and compassionate with loving-heart, harbouring no ill-will shall we abide, enfolding even these bandits with thoughts of loving-kindness. And forth from them proceeding, we shall abide radiating the whole world with thoughts of loving-kindness, expansive, measureless, benevolent and unified.”

Practicing patience and tolerance, instead of seeing the ugliness in others, a bodhisatta tries to seek the good and beautiful in all.

khantī: patience; forbearance. This is an excellent quality much praised in Buddhist scriptures. It can only be developed easily if restlessness and aversion have already been subdued in the mind, as is done by meditation practice. Impatience which has the tendency to make one rush around and thus miss many good chances, results from the inability to sit still and let things sort themselves out, which sometimes they may do without one’s meddling. The patient man has many a fruit fall into his lap which the go-getter misses. One of them is a quiet mind, for impatience churns the mind up and brings with it the familiar anxiety-diseases of the modern business world. Patience quietly endures–it is this quality which makes it so valuable in mental training and particularly in meditation. It is no good expecting instant enlightenment after five minutes practice. Coffee may be instant but meditation is not and only harm will come of trying to hurry it up. For ages the rubbish has accumulated, an enormous pile of mental refuse and so when one comes along at first with a very tiny teaspoon and starts removing it, how fast can one expect it to disappear? Patience is the answer and determined energy to go with it. The patient meditator really gets results of lasting value, the seeker after ‘quick methods’ or ‘sudden enlightenment’ is doomed by his own attitude to long disappointment.

Indeed, it must soon become apparent to anyone investigating the Dhamma that these teachings are not for the impatient. A Buddhist views his present life as a little span perhaps of eighty years or so, and the last one so far of many such lives. Bearing this in mind, he determines to do as much in this life for the attainment of Enlightenment as possible but he does not over-estimate his capabilities and just quietly and patiently gets on with living the Dhamma from day to day. Rushing into Enlightenment (or what one thinks it is) is not likely to get one very far, that is unless one is a very exceptional character who can take such treatment and most important, one is devoted to a very skilful master of meditation.

With patience one will not bruise oneself but go carefully step by step along the may. We learn that the Bodhisatta was well aware of this and that he cultured his mind with this perfection so that it was not disturbed by any of the untoward occurrences common in this world. He decided that he would be patient with exterior conditions–not be upset when the sun was too hot or the weather too cold; not be agitated by other beings which attacked his body, such as insects. Neither would he be disturbed when people spoke harsh words, lies or abuse about him, either to his face or behind his back. His patience was not even broken when his body was subjected to torment, blows, sticks and stones, tortures and even death itself he would endure steadily, so unflinching was his patience. Buddhist monks are advised to practice in the same way.

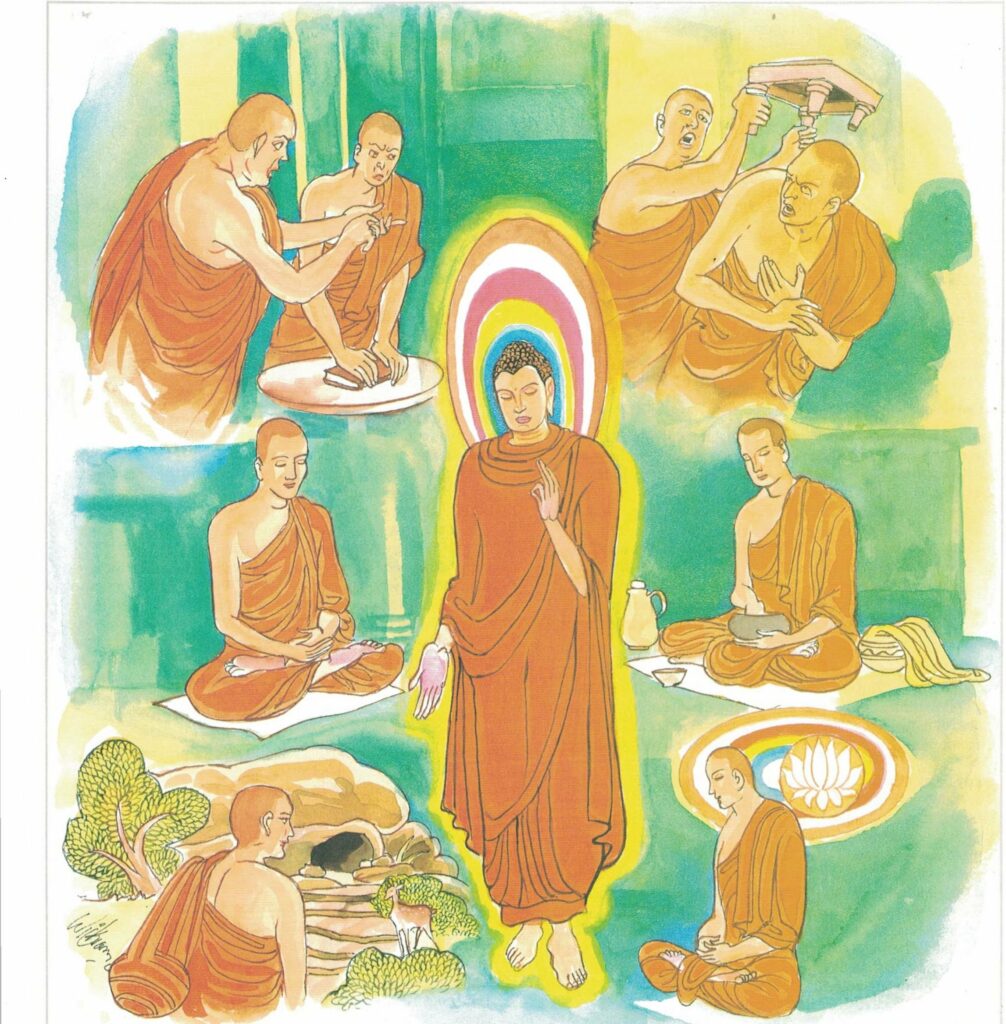

sacitta pariyodapanaṃ: clearing one’s mind. In the Buddhist system, the higher perceptions result from the purification of the mind. In consequence, mind-cultivation and meditation assumes an important place in the proper practice of Buddhism. The mental exercise known as meditation is found in all religious systems. Prayer is a form of discursive meditation, and in Hinduism the reciting of slokās and mantrās is employed to tranquillise the mind to a state of receptivity. In most of these systems the goal is identified with the particular psychic results that ensue, such as the visions that come in the semi-trance state, or the sounds that are heard. This is not the case in the forms of meditation practiced in Buddhism.

Comparatively little is known about the mind, its functions and its powers, and it is difficult for most people to distinguish between selfhypnosis, the development of mediumistic states, and the real process of mental clarification and direct perception which is the object of Buddhist mental development called bhāvanā (translated as meditation). The fact that mystics of every religion have induced in themselves states wherein they see visions and hear voices that are in accordance with their own religious beliefs, indicates that their meditation has resulted only in bringing to the surface of the mind the concepts already embedded in the deeper strata of their minds due to cultural conditioning. The Christian sees and converses with the saints of whom he already knows, the Hindu visualises the gods of the Hindu pantheon, and so on. When Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, the Bengali mystic, began to turn his thoughts towards Christianity, he saw visions of Jesus in his meditations, in place of his former eidetic images of the Hindu Avatārs.

The practiced hypnotic subject becomes more and more readily able to surrender himself to the suggestions made to him by the hypnotiser, and anyone who has studied this subject is bound to see a connection between the mental state of compliance he has reached and the facility with which the mystic can induce whatever kind of experiences he wills himself to undergo. There is still another possibility latent in the practice of meditation: the development of mediumistic faculties by which the subject can actually see and hear beings on different planes of existence, the devalokas and the realm of the unhappy ghosts, for example. These worlds being nearest to our own are the more readily accessible, and this could be the true explanation of the psychic phenomena of western spiritualism.

The object of Buddhist meditation, however, is none of these things. They may arise due to errors in meditation, but not only are they not its goal, but they are hindrances which have to be overcome. The Christian who has seen Jesus, or the Hindu who has conversed with Bhagavan Krishna may be quite satisfied that he has fulfilled the purpose of his religious life, but the Buddhist who sees a vision of the Buddha knows by that very fact that he has only succeeded in projecting a belief onto his own mental screen, for the Buddha after his Parinibbāna is, in his own words, no longer visible to anyone.

There is an essential difference, then, between Buddhist meditation and that practiced in other systems. The Buddhist embarking on a course of meditation does well to recognise this difference and to establish in his own mind a clear idea of what it is he is trying to do.

The root-cause of rebirth and suffering is unawareness (avijjā) conjoined with thirst (tanhā). These two causes form a vicious circle; on the one hand, concepts produce emotions, and on the other hand, emotions produce concepts. The phenomenal world has no meaning beyond the meaning given to it by our own interpretation.

When that interpretation is based on past biases we are subject to what is known as vipallāsa, or distortions, saññā-vipallāsa, distortion of perception, citta-vipallāsa, distortion of temper and diṭṭhi-vipallāsa, distortion of concepts which cause us to regard that which is impermanent (anicca) as permanent; that which is painful (dukkha) as pleasurable, and that which is impersonal (anatta), as personal. Consequently, we place a false interpretation on all the sensory experiences we gain through the six receptors of cognition, that is, the eye, ear, nose, tongue, sense of touch and mind (cakkhu, sota, ghāna, jivhā, kāya and mano āyatana). It is known that the phenomena we know through these channels of cognition, do not really correspond to the physical world. This has confirmed the Buddhist view. We are misguided by our own senses. Pursuing what we imagine to be desirable, an object of pleasure, we are in reality only following a shadow, trying to grasp a mirage. These phenomena are unstable, painful and impersonal. We ourselves, who chase the illusions, are also impermanent, subject to suffering and without any real personality; a shadow pursuing a shadow.

The purpose of Buddhist meditation, therefore, is to gain a more than intellectual understanding of this truth, to liberate ourselves from the delusion and thereby put an end both to unawareness and thirst. If the meditation does not produce results which are observable in the character of a person, and the whole attitude to life, it is clear that there is something wrong either with the system of meditation or with the method of practice. It is not enough to see lights, to have visions or to experience ecstasy. These phenomena are too common to be impressive to the Buddhist who really understands the purpose of Buddhist meditation.

In the Buddha’s great discourse on the practice of mindfulness, the Mahā-Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, both the object of meditation and the means of attaining it are clearly set forth. Attentiveness to the movements of the body, and the ever changing states of the mind, is to be cultivated, in order that their real nature is known. Instead of identifying these physical and mental phenomena with the false concept of self, we are to see them as they really are; as movements of a physical body, subject to physical laws of causality on the one hand, and as a successive series of sensations, emotional states and concepts, arising and passing away in response to external stimuli. They are to be viewed objectively, as though they were processes not associated with ourselves but as a series of impersonal phenomena.

From what can selfishness and egotism proceed if not from the concept of Self (sakkāyadiṭṭhi)? If the practice of any form of meditation leaves selfishness or egotism unabated, it has not been successful. A tree is judged by its fruits and a man by his actions; there is no other criterion. Particularly is this true in Buddhist psychology, because the man is his actions. In the truest sense it is only the continuity of kamma and Vipāka which can claim any persistent identity, not only through the different phases of one’s life but also through the different lives in this cycle of birth and death called saṃsāra. Attentiveness with regard to body and mind serves to break down the illusion of self, and, not only that, it also eliminates craving and attachment to external objects, so that ultimately, there is neither the self that craves, nor any object of craving. It is a long and arduous discipline, and one that can only be undertaken in retirement. A temporary course of this discipline can bear good results in that it establishes an attitude of mind which can be applied to some degree in the ordinary situations of life. Detachment and objectivity are invaluable aids to clear thinking. They enable a man to sum up a given situation without bias, personal or otherwise, and to act in that situation with courage and discretion. Another gift it bestows is that of concentration–the ability to keep the mind on any subject. This is the great secret of success in any undertaking. The mind is hard to tame; it roams here and there restlessly as the wind, or like an untamed horse, but when it is fully under control, it is the most powerful instrument in the whole universe.

In the first place, he is without fear. Fear arises because we associate mind and body (nāma–rūpa) with self, consequently, any harm to either is considered to be harm done to oneself. But he who has broken down this illusion, by realising that the five khandha process is merely the manifestation of cause and effect, does not fear death or misfortune. He remains alike in success and failure, unaffected by praise or blame. The only thing he fears is demeritorious action, because he knows that no thing or person in the world can harm him except himself, and as his detachment increases, he becomes less and less liable to demeritorious deeds. Unwholesome action comes of an unwholesome mind, and as the mind becomes purified, healed of its disorders, negative kamma ceases to accumulate. He comes to have a horror of wrong action and to take greater and greater delight in those deeds which stem from alobha, adosa and amoha–generosity, benevolence and wisdom.