Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 172:

yo ca pubbe pamajjitvā pacchā so nappamajjati |

so imaṃ lokaṃ pabhāseti abbhā mutto’va candimā || 172 ||

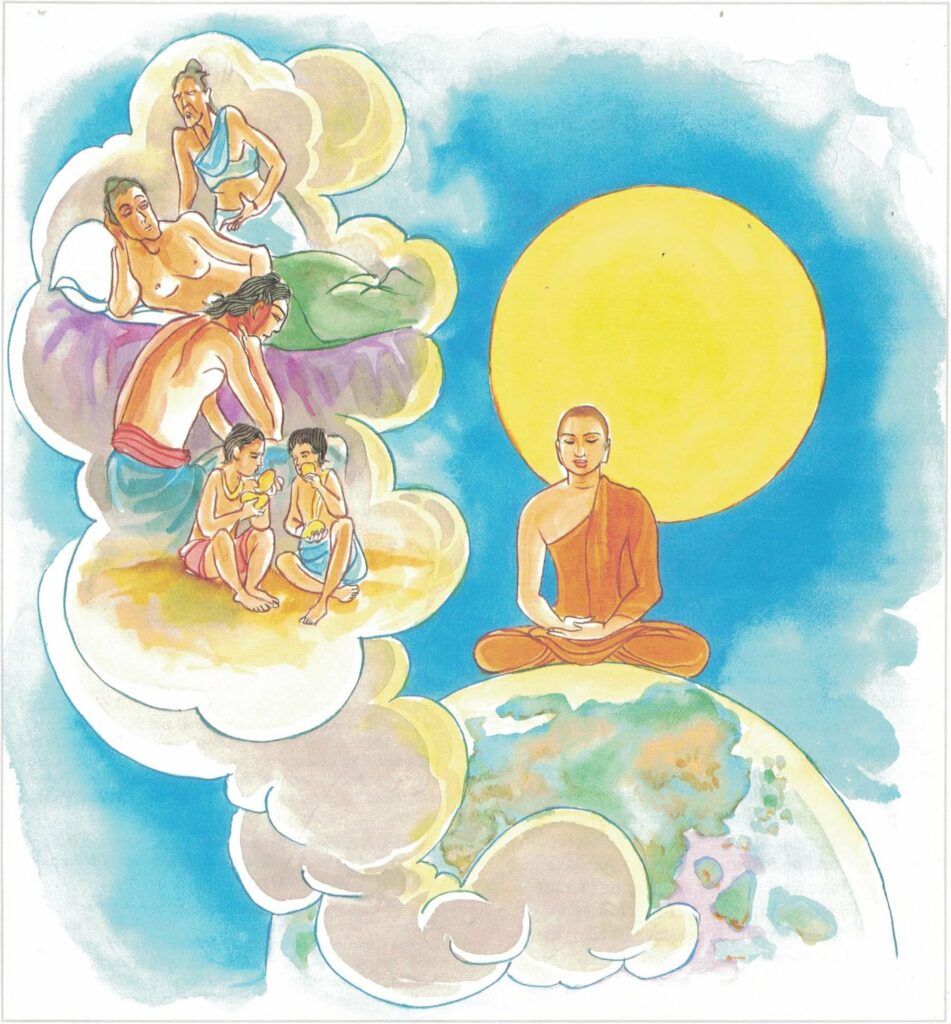

172. Whoso was heedless formerly but later lives with heedfulness illuminates all this world as moon when free from clouds.

The Story of Venerable Sammuñjanī

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this Verse, with reference to Venerable Sammuñjanī.

Venerable Sammuñjanī spent most of his time sweeping the precincts of the monastery. At that time, Venerable Revata was also staying at the monastery: unlike Sammuñjanī, Venerable Revata spent most of his time in meditation or deep mental absorption. Seeing Venerable Revata’s behaviour, Venerable Sammuñjanī thought the other monk was just idling away his time. Thus, one day Sammuñjanī went to Venerable Revata and said to him, “You are being very lazy, living on the food offered out of faith and generosity: don’t you think you should sometimes sweep the floor or the compound or some other place?” To him, Venerable Revata replied, “Friend, a monk should not spend all his time sweeping. He should sweep early in the morning, then go out on the alms-round. After the meal, contemplating his body he should try to perceive the true nature of the aggregates, or else, recite the texts until nightfall. Then he can do the sweeping again if he so wishes.” Venerable Sammuñjanī strictly followed the advice given by Venerable Revata and soon attained arahatship.

Other monks noticed some rubbish piling up in the compound and they asked Sammuñjanī why he was not sweeping as much as he used to, and he replied, “When I was not mindful, I was all the time sweeping: but now I am no longer unmindful.” When the monks heard his reply they were skeptical: so they went to the Buddha and said, “Venerable! Venerable Sammuñjanī falsely claims himself to be an arahat: he is telling lies.” To them the Buddha said, “Sammuñjanī has indeed attained arahatship: he is telling the truth.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 172)

yo pubbe pamajjitvā ca so pacchā nappamajjati

so abbhā mutto candimā iva imaṃ lokaṃ pabhāseti

Yo: if some one; pubbe: previously; pamajjitvā: having been deluded; ca so: he here too; pacchā: later on; nappamajjati: becomes disillusioned; so: he; abbhā mutto [mutta]: released from dark cloud; candimā iva: like the moon; imaṃ lokaṃ [loka]: this world; pabhāseti: illumines

An individual may have been deluded in the past. But later on corrects his thinking and becomes a disillusioned person. He, therefore, is like the moon that has come out from behind a dark cloud: thus, he illumines the world.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 172)

abbhā mutto candimā iva: like the moon that is released from the dark clouds. This image is used about those who have attained higher states of spirituality. The moon shines in all its brightness when it escapes dark clouds. When truth-seekers escape the bonds of worldliness, they, too, shine forth. The escape from the dark clouds of worldly hindrances takes place in several stages. When the jhānas are developed by temporarily removing the obscurants (Nīvarana) the mind is so purified that it resembles a polished mirror, where everything is clearly reflected in true perspective.

Discipline (sīla) regulates words and deeds: composure (samādhi) calms the mind: but it is insight (paññā) the third and the final stage, that enables the aspirant to sainthood to eradicate wholly the defilements removed temporarily by samādhi. At the outset, he cultivates purity of vision (diṭṭhi visuddhi) in order to see things as they truly are.

With calmed mind he analyses and examines his experience. This searching examination shows what he has called ‘I’ personality, to be merely an impersonal process of psycho-physical activity.

Having thus gained a correct view of the real nature of this so-called being, freed from the false notion of a permanent soul, he searches for the causes of this ego.

Thereupon, he contemplates the truth that all constructs are transitory (anicca), painful (dukkha), and impersonal (anatta). Wherever he turns his eyes he sees naught but these three characteristics standing out in bold relief. He realizes that life is a mere flux conditioned by internal and external causes. Nowhere does he find any genuine happiness, because everything is fleeting.