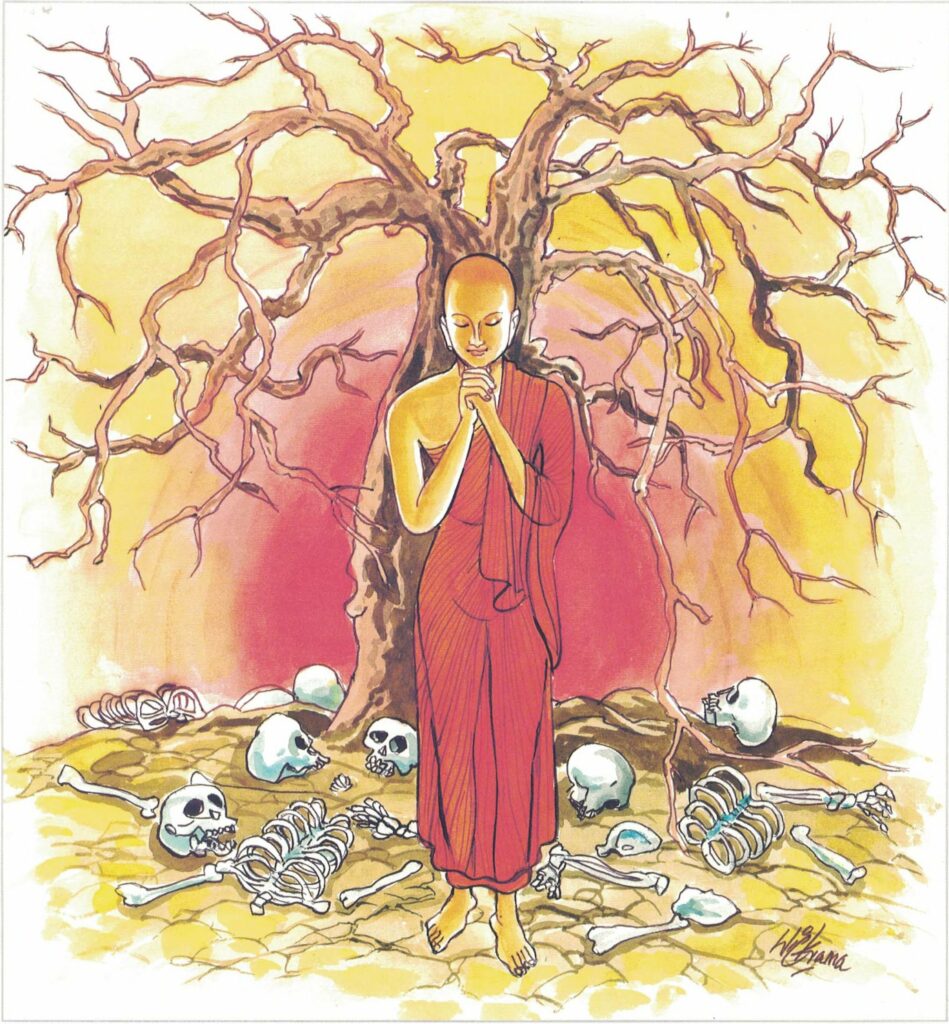

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 149:

yān’imāni apatthāni alāpūn’eva sārade |

kāpotakāni aṭṭhīni tāni disvāna kā rati || 149 ||

149. These dove-hued bones scattered in Fall, like long white gourds, what joy in seeing them?

The Story of Adhimānika Monks

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to some monks who over-estimated themselves.

A great number of monks, after taking a subject of meditation from the Buddha, went into the woods. There, they practiced meditation ardently and diligently and soon attained deep mental absorption (jhāna) and they thought that they were free from sensual desires and, therefore, had attained arahatship. Actually, they were only over-estimating themselves. Then, they went to the Buddha, with the intention of informing the Buddha about what they thought was their attainment of arahatship.

When they arrived at the outer gate of the Monastery, the Buddha said to the Venerable Ānanda, “Those monks will not benefit much by coming to see me now;let them go to the cemetery first and come to see me only afterwards.” The Venerable Ānanda then delivered the message of the Buddha to those monks, and they reflected, “The Buddha knows everything; he must have some reason in making us go to the cemetery first.” So they went to the cemetery.

There, when they saw the putrid corpses they could look at them as just skeletons, and bones, but when they saw some fresh dead bodies they realized, with horror, that they still had some sensual desires awakening in them. The Buddha saw them from his perfumed chamber and sent forth his radiance; then he appeared to them and said, “Monks! Seeing these bleached bones, is it proper for you to have any sensual desires in you?” At the end of the discourse, the monks attained arahatship.

Then the Buddha pronounced this stanza.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 149)

sārade apatthāni alāpūni iva kāpotakāni

yāni imāni aṭṭhīni tāni disvāna kā rati

sārade: during autumn; apatthāni: scattered carelessly; alāpūni iva: like gourds; kāpotakāni: grey coloured; yāni imāni: such; aṭṭhīni tāni: these bones; disvāna: having seen; kā rati: who ever will lust

In the dry autumnal season, one can see bones and skulls strewn around. These dry grey-hued skulls are like gourds thrown here and there. Seeing these, whoever will lust?

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 149)

aṭṭhīni: bones. The stanza describes a variety of human bones strewn in a cemetery. They symbolize the universal law of decay–jarā.

jarā: old age, decay. Old age (decay) is one of the three divine messengers. Divine messengers is a symbolic name for old age, disease and death, since these three things remind man of his future and rouse him to earnest striving. It is said, “Did you, O man, never see in the world a man or a woman eighty, ninety or a hundred years old, frail, crooked as a gable-roof, bent down, resting on crutches, with tottering steps, infirm, youth long since fled, with broken teeth, grey and scanty hair, or bald-headed, wrinkled, with blotched limbs? And did it never occur to you that you also are subject to old age, that you also cannot escape it? Did you never see in the world a man or a woman, who being sick, afflicted and grievously ill, and wallowing in their own filth, was lifted up by some people, and put down by others? And did it never occur to you that you also are subject to disease, that you also cannot escape it? Did you never see in the world the corpse of a man or a woman, one, or two, or three days after death, swollen up, blue-black in colour, and full of corruption? And did it never occur to you that you also are subject to death, that you also cannot escape it?”

When one sees the impermanence of everything in life: how everything one is attached to and dependent on, changing, parting or coming to destruction, what is left is only the emotional disturbance: the feeling of insecurity, loneliness, fear, anxiety, worry and unhappiness. The only way to find happiness is to learn to control the emotions and calm the mind, by changing the way we think. We have to become detached from things and independent emotionally. This is done by understanding that we do not own anything in the world, including what we call ourselves: the body, mind, and spirit.