Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 148:

parijiṇṇamidaṃ rūpaṃ roganiḍḍhaṃ pabhaṅguraṃ |

bhijjati pūtisandeho maraṇantaṃ hi jīvitaṃ || 148 ||

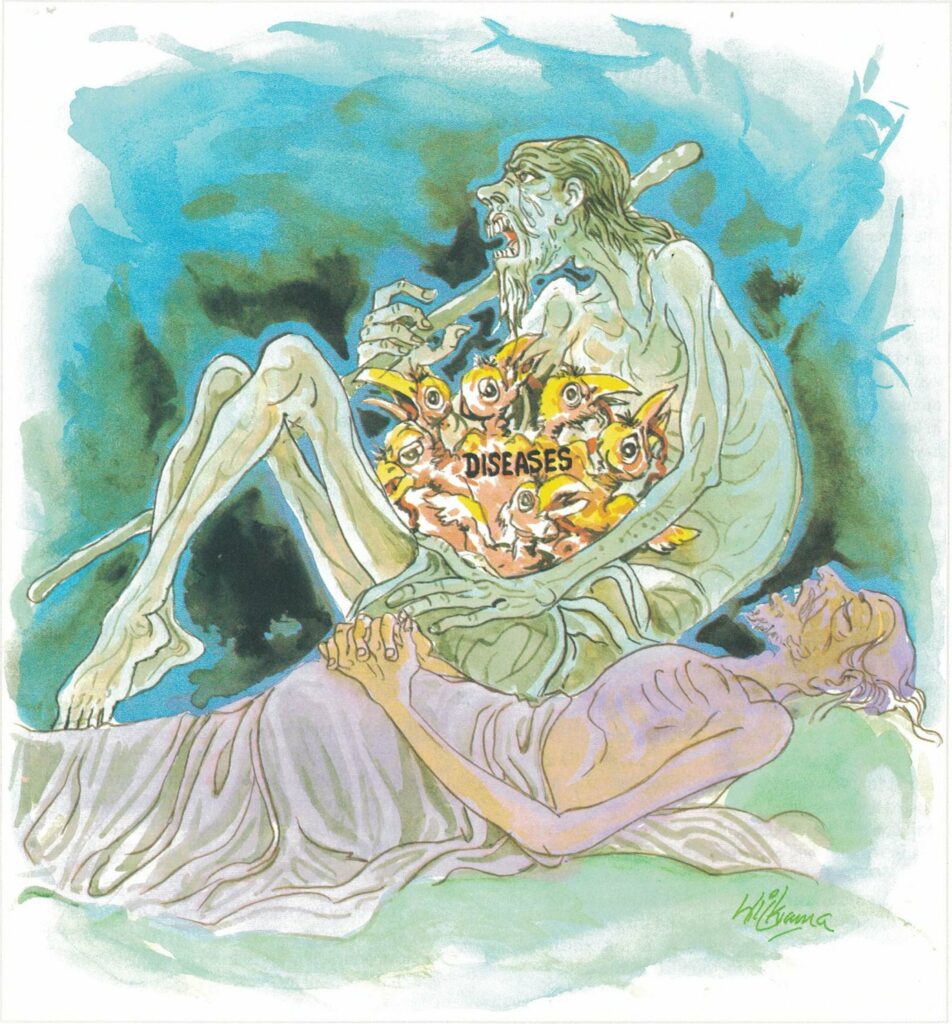

148. All decrepit is this body, diseases’ nest and frail; this foul mass is broken up for life does end in death.

The Story of Nun Uttarā

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to Nun Uttarā.

Nun Uttarā, who was one hundred and twenty years old, was one day returning from her alms-round when she met a monk and requested him to accept her offering of alms-food; so she had to go without food for that day. The same thing happened on the next two days. Thus Nun Uttarā was without food for three successive days and she was feeling weak. On the fourth day, while she was on her alms-round, she met the Buddha on the road where it was narrow. Respectfully, she paid obeisance to the Buddha and stepped back. While doing so, she accidentally stepped on her own robe and fell on the ground, injuring her head. The Buddha went up to her and said, “Your body is getting very old and infirm, it is ready to crumble, it will soon perish.” At the end of the discourse, Nun Uttarā attained sotāpatti fruition.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 148)

idaṃ rupaṃ parijiṇṇaṃ roganiḍḍhaṃ pabhaṅguraṃ

pūtisandeho bhijjati hi jīvitaṃ maraṇantaṃ

idaṃ rupaṃ [rupa]: this form: parijiṇṇaṃ [parijiṇṇa]: fully broken down; roganiḍḍhaṃ [roganiḍḍha]: (it is like) a nest of diseases; pabhaṅguraṃ [pabhaṅgura]: disintegrates easily; pūtisandeho [pūtisandeha]: putrid matter oozes out of it; bhijjati: it breaks apart easily; hi jīvitaṃ maraṇantaṃ [maraṇanta]: Death ends it

This form–this body–is fully broken down. It is truly a den of diseases. It disintegrates easily. Out of its nine orifices, putrid matter oozes constantly. It breaks apart. Death puts an end to it.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 148)

jīvitaṃ maraṇantaṃ: life ends in death. The central purpose of this stanza is to drive home the fact of impermanence of life. Impermanence (aniccā) is the first of three characteristics of existence (tilakkhana). It is from the fact of impermanence that, in most texts, the other two characteristics, suffering (dukkha) and not-self (anattā), are derived. Impermanence of things is the rising, passing and changing of things, or the disappearance of things that have become or arisen. The meaning is that these things never persist in the same way, but that they are vanishing and dissolving from moment to moment.

Impermanence is a basic feature of all conditioned phenomena, be they material or mental, coarse or subtle, one’s own or external. All formations are impermanent. That the totality of existence is impermanent is also often stated in terms of the five aggregates, the twelve sense bases. Only Nibbāna which is unconditioned and not a formation (asankata), is permanent.

The insight leading to the first stage of deliverance, stream-entry, is often expressed in terms of impermanence: “Whatever is subject to origination, is subject to cessation.” In his last exhortation, before his Parinibbāna, the Buddha reminded his monks of the impermanence of existence as a spur to earnest effort: “Behold now, monks, I exhort you. Formations are bound to vanish. Strive earnestly!”

Without deep insight into the impermanence and unsubstantiality of all phenomena of existence there is no attainment of deliverance. Hence comprehension of impermanence gained by direct meditative experience, heads two lists of insight knowledge: (a) contemplation of impermanence is the first of the eighteen chief kinds of insight; (b) the contemplation of arising and vanishing is the first of nine kinds of knowledge which lead to the purification by knowledge and vision of the path congress. Contemplation of impermanence leads to the conditionless deliverance. As herein the faculty of confidence is outstanding, he who attains in that way the path of stream-entry, is called a faith devotee and at the seven higher stages he is called faith-liberated.

pabhaṅguraṃ: the body is likely to disintegrate easily.

pūtisandeho: putrid matter oozes out of its nine orifices.

aniccā: impermanence. Regarding impermanence, though we may see leaves on a tree, some young and unfolding, some mature, while others are sere and yellow, impermanence does not strike home in our hearts. Although our hair changes from black, to grey, to white over the years, we do not realize what is so obviously being preached by this change–impermanence. There is a vast difference between occasionally acquiescing in the mind or admitting with the tongue the truth of impermanence, and actually realizing it constantly in the heart. The trouble is that while intellectually we may accept impermanence as valid truth, emotionally we do not admit it, specially in regard to I and mine. But whatever our unskillful emotions of greed may or may not admit, impermanence remains a truth, and the sooner we come to realize through insight that it is a truth, the happier we shall be, because our mode of thought will thus be nearer to reality.