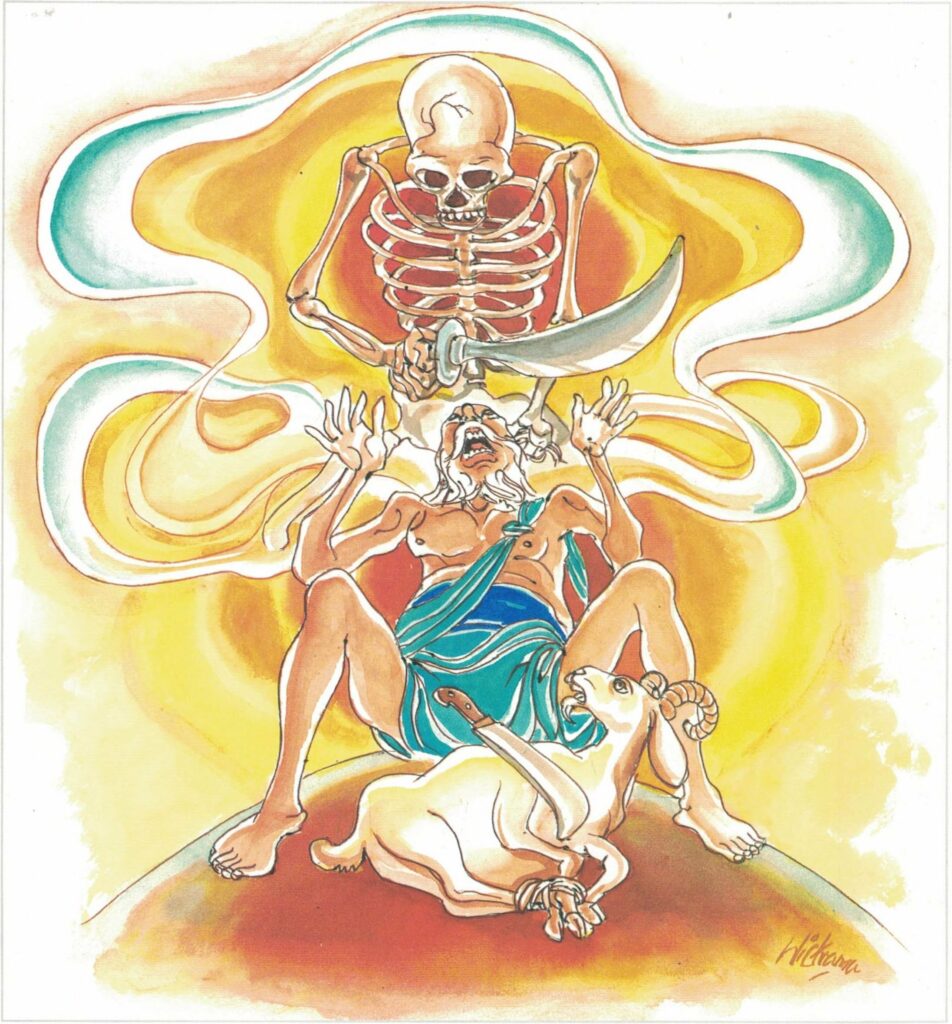

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 129:

sabbe tasanti daṇaḍassa sabbe bhāyanti maccuno |

attānaṃ upamaṃ katvā na haneyya na ghātaye || 129 ||

129. All tremble at force, of death are all afraid. Likening others to oneself kill not nor cause to kill.

The Story of a Group of Six Monks

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to a group of six monks.

Once, a group of monks was cleaning up a building in the Jetavana Monastery with the intention of occupying it, when they were interrupted in their task by another group of monks who had arrived at the scene. The monks who had come later told the first group of monks who were cleaning the building, “We are elderly and more senior to you, so you had better accord us every respect and give way to us; we are going to occupy this place and nothing will stop us from doing so.”

However, the first group of monks resisted the unwelcome intrusion by the senior monks and did not give in to their demands, whereupon they were beaten up by the senior monks till they could not bear the beatings and cried out in pain.

News of the commotion had reached the Buddha who, on learning about the quarrel between the two groups of monks, admonished them and introduced the disciplinary rule whereby monks should refrain from hurting one another.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 129)

sabbe daṇḍassa tasanti sabbe maccuno bhāyanti

attānaṃ upamaṃ katvā na haneyya na ghātaye

sabbe. all; daṇḍassa: at punishment; tasanti. are frightened; sabbe: all; maccuno [maccuna]: death; bhāyanti: fear; attānaṃ [attāna]: one’s own self, upamaṃ katvā: taking as the example; na haneyya: do not kill; na ghātaye: do not get anyone else to kill

All tremble at violence, all fear death. Comparing oneself with others do not harm, do not kill.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 129)

maccuno bhāyanti: fear death. Buddhism has analyzed the phenomenon of death quite extensively. The Paticca-Samuppāda describes the process of rebirth in subtle technical terms and assigns death to one of the following four causes:

1) Exhaustion of the reproductive kammic energy (kammakkhaya). The Buddhist belief is that, as a rule, the thought, volition, or desire, which is extremely strong during lifetime, becomes predominant at the time of death and conditions the subsequent birth. In this last thought-process is present a special potentiality. When the potential energy of this reproductive (janaka). Kamma is exhausted, the organic activities of the material form in which is embodied the life-force, cease even before the end of the life-span in that particular place. This often happens in the case of beings who are born in states of misery (apāya) but it can also happen in other planes.

2) The expiration of the life-term (āyukkhaya), which varies in different planes. Natural deaths, due to old age, may be classed under this category. There are different planes of existence with varying agelimits. Irrespective of the kammic force that has yet to run, one must, however, succumb to death when the maximum age-limit is reached. If the reproductive kammic force is extremely powerful, the kammic energy rematerialises itself in the same plane or, as in the case of devas, in some higher realm.

3) The simultaneous exhaustion of the reproductive kammic energy and the expiration of the life-term (ubhayakkhaya).

4) The opposing action of a stronger kamma unexpectedly obstructing the flow of the reproductive kamma before the life-term expires (upacchedaka-kamma). Sudden untimely deaths of persons and the deaths of children are due to this cause. A more powerful opposing force can check the path of a flying arrow and bring it down to the ground. So a very powerful kammic force of the past is capable of nullifying the potential energy of the last thought-process, and may thus destroy the psychic life of the being. The death of Venerable Devadatta, for instance, was due to a destructive kamma which he committed during his lifetime.

The first three are collectively called timely deaths (kāla-marana), and the fourth is known as untimely death (akālamarana). An oil lamp, for instance, may get extinguished owing to any of the following four causes–namely, the exhaustion of the wick, the exhaustion of oil, simultaneous exhaustion of both wick and oil, or some extraneous cause like a gust of wind. So may death be due to any of the foregoing four causes.

Very few people, indeed, are prepared to die. They want to live longer and longer, a delusion which contemporary research is making more possible to realize. The craving for more and more of this life is somewhat toned down, if one believes, as many do, that this is only one life of a series. Plenty more lives are available to those who crave for them and work begun in this one does not have to be feverishly rushed to a conclusion but may be taken up again in subsequent births. The actual pains of dying are, of course, various and not all people go through physical agonies. But there is distress of another sort; the frightful stresses which are set up in the mind of one whose body is dying–against his will. This is really the final proof that the body does not belong to me, for if it did, I could do whatever I wanted with it; but at the time of death, although I desire continued life, it just goes and dies–and there is nothing to be done about it. If I go towards death unprepared, then, at the time when the body is dying, fearful insecurity will be experienced, the result of having wrongly identified the body as myself.