Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 112:

yo ca vassasataṃ jīve kusīto hīnavīriyo |

ekāhaṃ jīvitaṃ seyyo viriyamā rabhato daḷhaṃ || 112 ||

112. Though one should live a hundred years lazy, of little effort, yet better is life for a single day strongly making effort.

The Story of Venerable Sappadāsa

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to Venerable Sappadāsa.

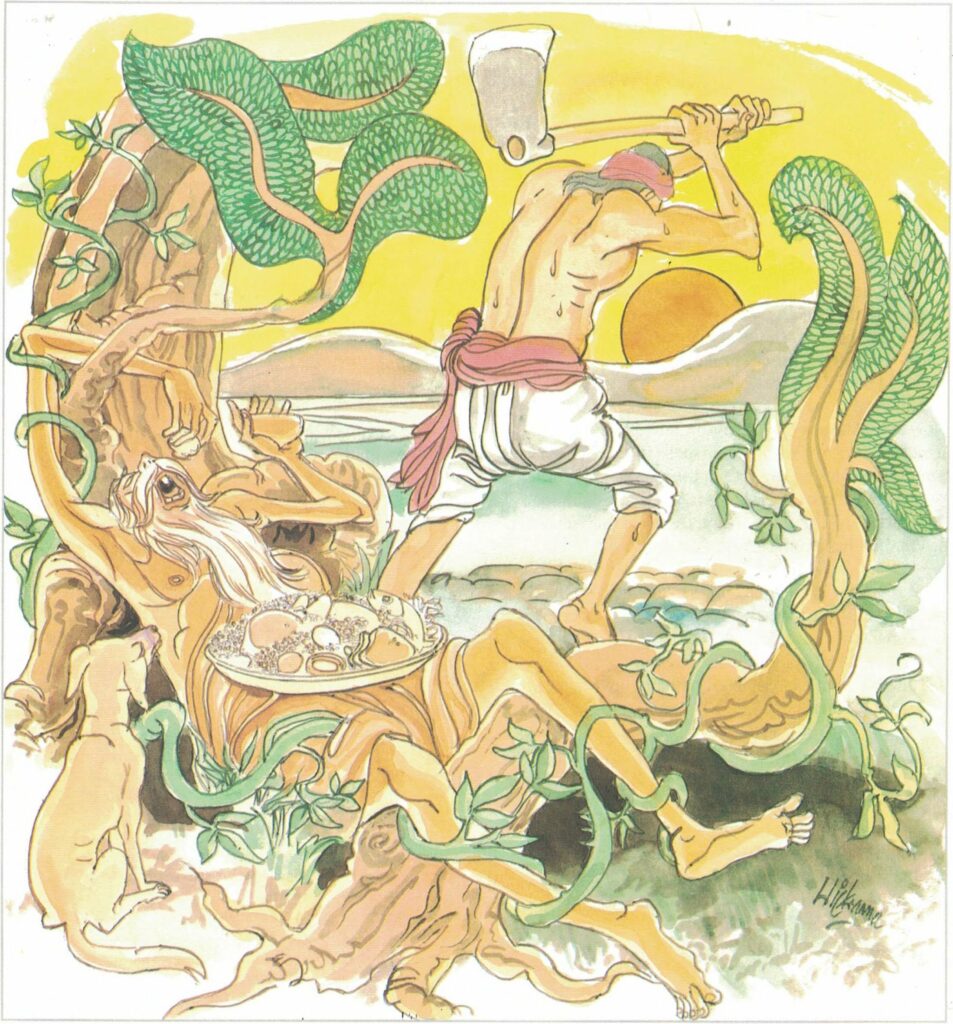

Once a monk was not feeling happy with the life of a monk; at the same time he felt that it would be improper and humiliating for him to return to the life of a householder. So he thought it would be better to die. So thinking this, on one occasion, he put his hand into a pot where there was a snake but the snake did not bite him. This was because in a past existence the snake was a slave and the monk was his master. Because of this incident the monk was known as Venerable Sappadāsa. On another occasion, Venerable Sappadāsa took a razor to cut his throat; but as he placed the razor on his throat he reflected on the purity of his morality practice throughout his life as a monk and his whole body was suffused with delightful satisfaction (pīti) and bliss (sukha). Then detaching himself from pīti, he directed his mind to the development of insight knowledge and soon attained arahatship, and he returned to the monastery.

On arrival at the monastery, other monks asked him where he had been and why he took the knife along with him. When he told them about his intention to take his life, they asked him why he did not do so. He answered, I originally intended to cut my throat with this knife, but I have now cut off all moral defilements with the knife of insight knowledge.” The monks did not believe him; so they went to the Buddha and asked, “Venerable Sir, this monk claims that he has attained arahatship as he was putting the knife to his throat to kill himself. Is it possible to attain arahatta magga within such a short time?” To them the Buddha said, “Monks! Yes, it is possible; for one who is zealous and strenuous in the practice of tranquillity and insight development, arahatship can be gained in an instant. As the monk walks in meditation, he can attain arahatship even before his raised foot touches the ground.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 112)

kusīto hīnavīriyo yo ca vassasataṃ jīve

daḷhaṃ viriyaṃ ārabhato ekāhaṃ jīvitaṃ seyyo

kusīto [kusīta]: lazy; hīnavīryo [hīnavīrya]: without initiative, lethargic; yo: an individual; ca: if; vassasataṃ [vassasata]: hundred years; jīve: were to live; daḷhaṃ viriyaṃ [viriya]: full of effort; ārabhato [ārabhata]: who develops; ekāhaṃ jīvitaṃ [jīvita]: even one day’s life; seyyo [seyya]: is noble

A single day’s life of a wise person who is capable of strenuous effort, is nobler than even hundred years of life of an individual who is lazy, incapable of making an effort and is wanting in initiative.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 112)

viriyaṃ: effort; specifically spiritual effort. Closely allied with Paññā (wisdom) is Viriya (Perseverance). Here, Viriya does not mean physical strength though this is an asset, but mental vigour or strength of character, which is far superior. It is defined as the persistent effort to purify the mind. Firmly establishing himself in this virtue, the Bodhisatta develops viriya and makes it one of his prominent characteristics.

The Viriya of a Bodhisatta is clearly depicted in the Mahājanaka Jātaka. Shipwrecked in the open sea for seven days he struggled on without once giving up hope until he was finally rescued. Failures he views as steps to success, opposition causes him to double his exertion, dangers increase his courage. Cutting his way through difficulties, which impair the enthusiasm of the feeble, surmounting obstacles, which dishearten the ordinary, he looks straight towards his goal. Nor does he ever stop until his goal is reached. To Māra who advised the Bodhisatta to abandon his quest, he said, “Death, in battle with passions seems to me more honourable than a life of defeat.” Just as his wisdom is always directed to the service of others, so also is his fund of energy. Instead of confining it to the narrow course leading to the realization of personal ends, he directs it into the open channel of activities that tend to universal happiness. Ceaselessly and untiringly he works for others, expecting no remuneration in return or reward. He is ever ready to serve others to the best of his ability.

In certain respects, Viriya plays an even greater part than Paññā in the achievement of the goal. In one who treads the noble eight-fold path, right effort (sammā vāyāma or viriya) prevents the arising of evil states, removes those which have arisen, cultivates good states, and maintains and develops those good states which have already arisen. It serves as one of the seven factors of enlightenment (viriya sambojjhanga). It is one of the four means of accomplishment (viriyiddhipāda). It is viriya that performs the function of the four modes of right endeavour (sammappadhāna). It is one of the five powers (viriya bala) and one of the five controlling faculties (viriyindriya).

Viriya therefore may be regarded as an officer that performs nine functions. It is this persistent effort to develop the mind that serves as a powerful hand to achieve all ends.