Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 109:

abhivādanasīlissa niccaṃ vaddhāpacāyino |

cattārā dhammā vaḍḍhanti āyu vaṇṇo sukhaṃ balaṃ || 109 ||

109. For one of respectful nature who ever the elders honours, long life and beauty, joy and strength, these qualities increase.

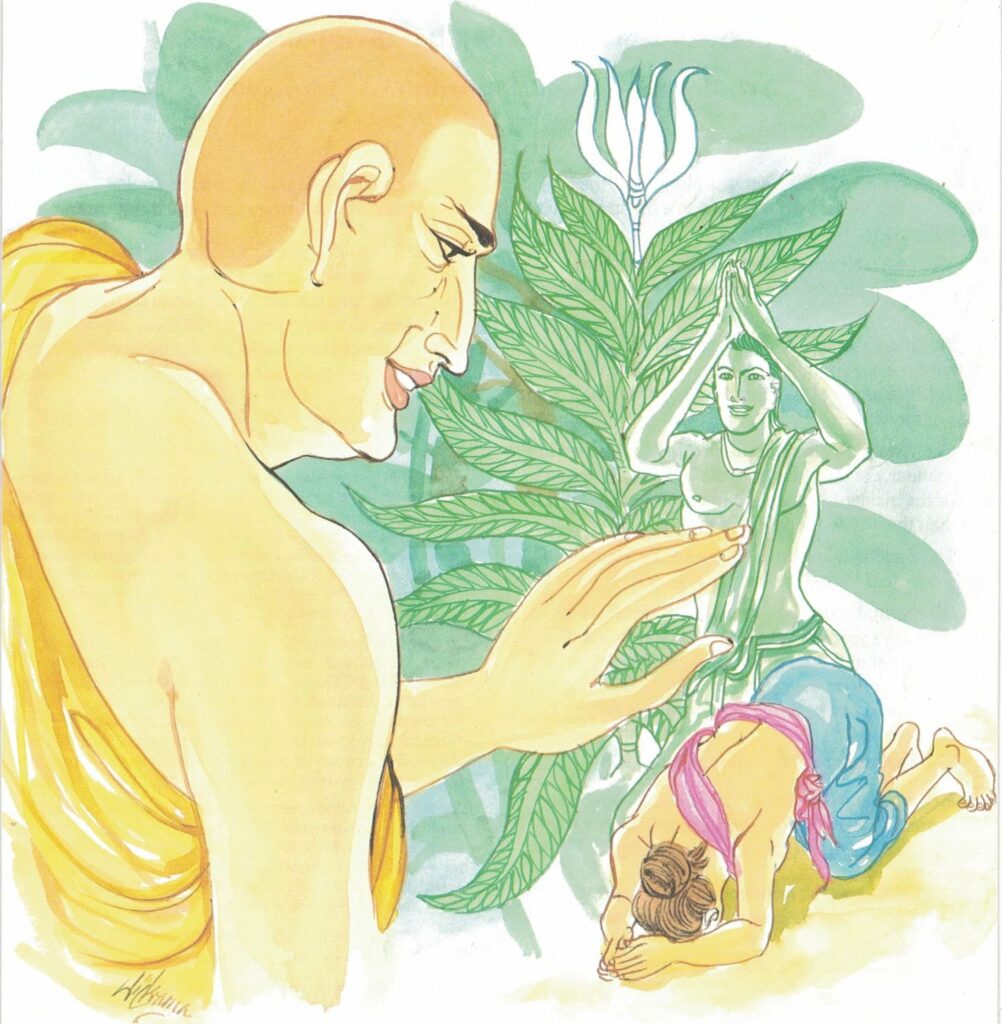

The Story of Āyuvaḍḍhanakumāra

While residing in a village monastery near Dīghalanghika, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to Āyuvaḍḍhanakumāra.

Once, there were two hermits who lived together practicing religious austerities for forty-eight years. Later, one of the two left the hermit life and got married. After a son was born, the family visited the old hermit and paid obeisance to him. To the parents the hermit said, “May you live long.” but he said nothing to the child. The parents were puzzled and asked the hermit the reason for his silence. The hermit told them that the child would live only seven more days and that he did not know how to prevent his death, but the Buddha might know how to do it.

So the parents took the child to the Buddha; when they paid obeisance to the Buddha, he also said, “May you live long” to the parents only and not to the child. The Buddha also predicted the impending death of the child. To prevent his death, the parents were told to build a pavilion at the entrance to the house, and put the child on a couch in the pavilion. Then some monks were sent there to recite the parittās (protective chants) for seven days. On the seventh day the Buddha himself came to that pavilion; the devas from all over the universe also came. At that time the evil spirit Avaruddhaka was at the entrance, waiting for a chance to take the child away. But as more powerful devas arrived the evil spirit had to step back and make room for them so that he had to stay at a place two leagues away from the child. That whole night, recitation of parittās continued, thus protecting the child. The next day, the child was taken up from the couch and made to pay obeisance to the Buddha. This time, the Buddha said “May you live long” to the child. When asked how long the child would live, the Buddha replied that he would live up to one hundred and twenty years. So the child was named Āyuvaḍḍhana.

When the child grew up, he went about the country with a company of five hundred fellow devotees. One day, they came to the Jetavana Monastery, and the monks, recognizing him, asked the Buddha, “For beings is there any means of gaining longevity?” To this question the Buddha answered, “By respecting and honouring the elders and those who are wise and virtuous, one would gain not only longevity, but also beauty, happiness and strength.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 109)

abhivādana sīlissa niccaṃ vaḍḍhāpacāino āyu

vaṇṇo sukhaṃ balaṃ cattāro dhammā vaḍḍhanti

abhivādana sīlissa: of those who are in the habit of honouring and respecting; niccaṃ [nicca]: constantly; vaḍḍhāpacāino [vaḍḍhāpacāina]: those who are developed and mature in mind; āyu: length of life; vanno [vanna]: complexion; sukhaṃ [sukha]: comfort; balaṃ [bala]: strength; cattāro dhammā: four things; vaḍḍhanti: increase

If a person is in the habit of constantly honouring and respecting those who are developed and mature, their lives improve in four ways. Their life span soon increases. Their complexion becomes clearer. Their good health and comfort will improve. Their vigour and stamina too will increase.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 109)

vaḍḍhāpacāino: the developed and the mature. This stanza extols the virtue of honouring those who are spiritually evolved. In terms of traditional commentaries, there are four categories that should be considered as ‘mature’ and as deserving honour.

The four categories are:

(1) Jātivuddha: mature or higher in terms of race. Among some groups of people there is the convention that some categories of race should be considered superior. Though this form of superiority is not accepted in Buddhism, the commentaries recognize its existence;

(2) Gotta vuddha: deserving honour due to caste or clan superiority In some systems this kind of superiority is accepted, but not in the Buddhist system;

(3) Vayo vuddha: superiority through age. In most cultures this form of honour is valid. Those younger in years always respect those who are superior to them in age;

(4) Guṇa vuddha: superior in terms of character. In the Buddhist Sangha hierarchy, this system prevails. In the Buddhist system all lay men honour all Buddhist monks because they are committed to certain superior principles of living even though the Buddhist monk may have been initiated into the order only a few seconds ago.