Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 158:

attānam’eva paṭhamaṃ patirūpe nivesaye |

athaññam’anusāseyya na kilisseyya paṇḍito || 158 ||

158. One should first establish oneself in what is proper. One may then teach others, and wise, one is not blamed.

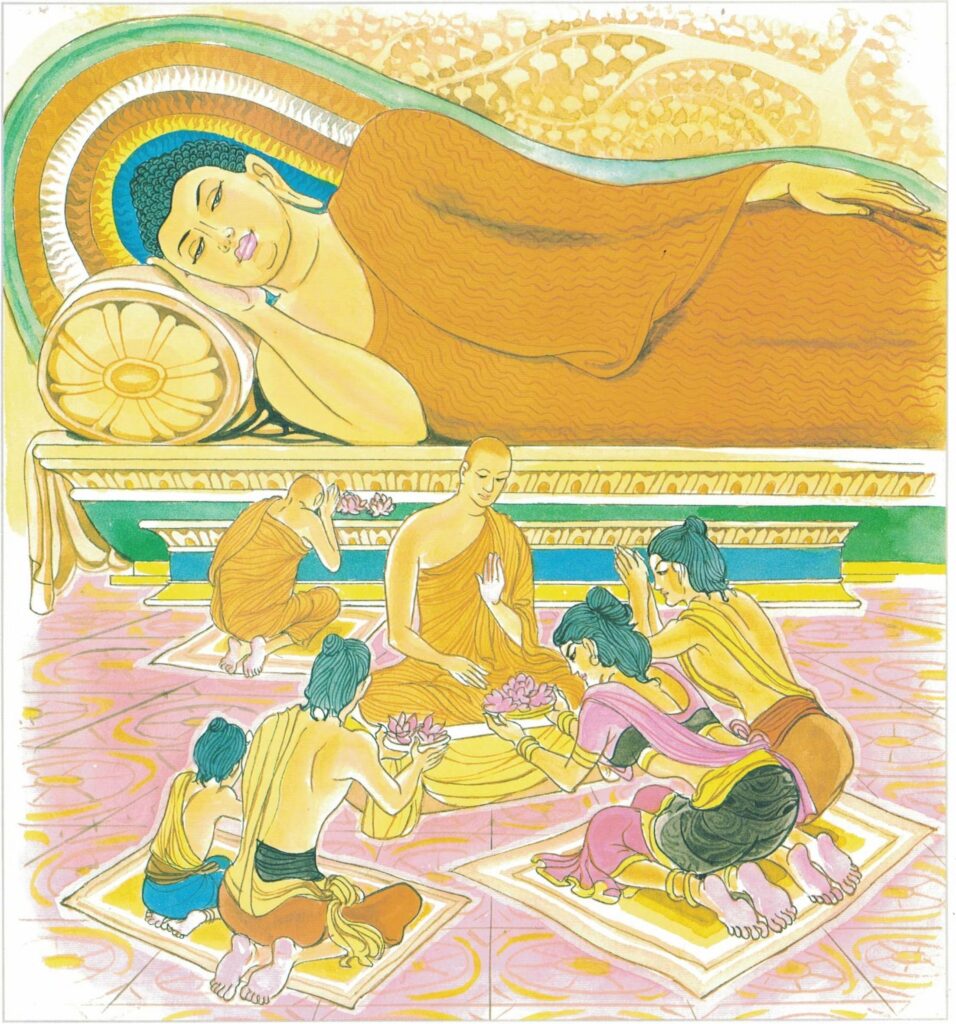

The Story of Venerable Upananda Sākyaputta

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to Upananda, a monk of the Sākyan clan.

Upananda was a very eloquent preacher. He used to preach to others not to be greedy and to have only a few wants and would talk eloquently on the merits of contentment and frugality (appicchatā) and austere practices (dhūtāngas). However, he did not practice what he taught and took for himself all the robes and other requisites that were given by others.

On one occasion, Upananda. went to a village monastery just before the vassa (rainy season). Some young monks, being impressed by his eloquence, asked him to spend the vassa in their monastery. He asked them how many robes each monk usually received as donation for the vassa in their monastery and they told him that they usually received one robe each. So he did not stop there, but he left his slippers in that monastery. At the next monastery, he learned that the monks usually received two robes each for the vassa; there he left his staff. At the next monastery, the monks received three robes each as donation for the vassa;there he left his water bottle. Finally, at the monastery where each monk received four robes, he decided to spend the vassa.

At the end of the vassa, he claimed his share of robes from other monasteries where he had left his personal effects. Then he collected all his things in a cart and came back to his old monastery. On his way, he met two young monks who were having a dispute over the share of two robes and a valuable velvet blanket which they had between them. Since they could not come to an amicable settlement, they asked Upananda to arbitrate. Upananda gave one robe each to them and took the valuable velvet blanket for having acted as an arbitrator.

The two young monks were not satisfied with the decision but they could do nothing about it. With a feeling of dissatisfaction and dejection, they went to the Buddha and reported the matter. To them the Buddha said, “One who teaches others should first teach himself and act as he has taught.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 158)

paṭhamaṃ attānaṃ eva patīrūpe nivesaye

atha aññaṃ anusāseyya paṇḍito na kilisseyya

paṭhamaṃ [paṭhama]: in the first instance; attānaṃ eva: one’s own self; patīrūpe: in the proper virtue; nivesaye: establish; atha: after that; aññaṃ [añña]: others; anusāseyya: advise; paṇḍito [paṇḍita]: the wise man; na kilisseyya: does not get blemished

If you are keen to advise others, in the first instance establish yourself in the proper virtues. It is only then that you become fit to instruct others.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 158)

paṭhamaṃ attānaṃ eva: in the first instance, one’s own self. This exhortation does not in any way imply that the Buddha advocated selfishness. On the contrary, the Buddha only places priorities right. First, look after your liberation. Then only should you look after the others. This is in keeping with the essence of the Buddha’s Dhamma–the Teaching of the Buddha. It only means that without overcoming your own selfishness first, you cannot help others to do so. Dhamma is, literally, that which supports; it is the truth within us, relying upon which and by practicing which, we can cross over the ocean of troubles and worries. Dhamma is also the formulations of the truth which we can practice if we are interested to do so. In Dhamma there is no creed and there are no dogmas. A Buddhist is free to question any part of the Buddha’s Dhamma, indeed, the Buddha has encouraged him to do so. There is nothing which he is forbidden to question, no teaching about which he must just close his mind and blindly believe. This is because faith in a Buddhist sense is not a blind quality but is combined with wisdom. Thus a person is attracted towards the dhamma because he has some wisdom to perceive a little truth in it, meanwhile accepting with faith those teachings as yet unproved by him. In practicing the Dhamma, he finds that it does in fact work–that it is practical, and so his confidence grows. With the growth of his confidence he is able to practice more deeply, and doing this he realizes more of the truth–so confidence grows stronger. Thus faith and wisdom complement and strengthen each other with practice. In this case, as in many other Buddhist teachings, it is easy to see why Buddhist teaching is symbolized by a wheel, for this is a dynamic symbol. But one who has seen the Dhamma-truth in himself, being rid of all mental defilements and troubles, an arahat, has no faith, he has something much better, adamantine wisdom.