Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 143-144:

hirīnisedho puriso koci lokasmiṃ vijjati |

yo nindaṃ apabodhati asso bhadro kasāmiva || 143 ||

asso yathā bhadro kasāniviṭiṭho ātāpino saṃvegino bhavātha |

saddhāya sīlena ca vīriyena ca samādhinā dhammavinicchayena ca |

sampannavijjācaraṇā patissatā pahassatha dukkhamidaṃ anappakaṃ || 144 ||

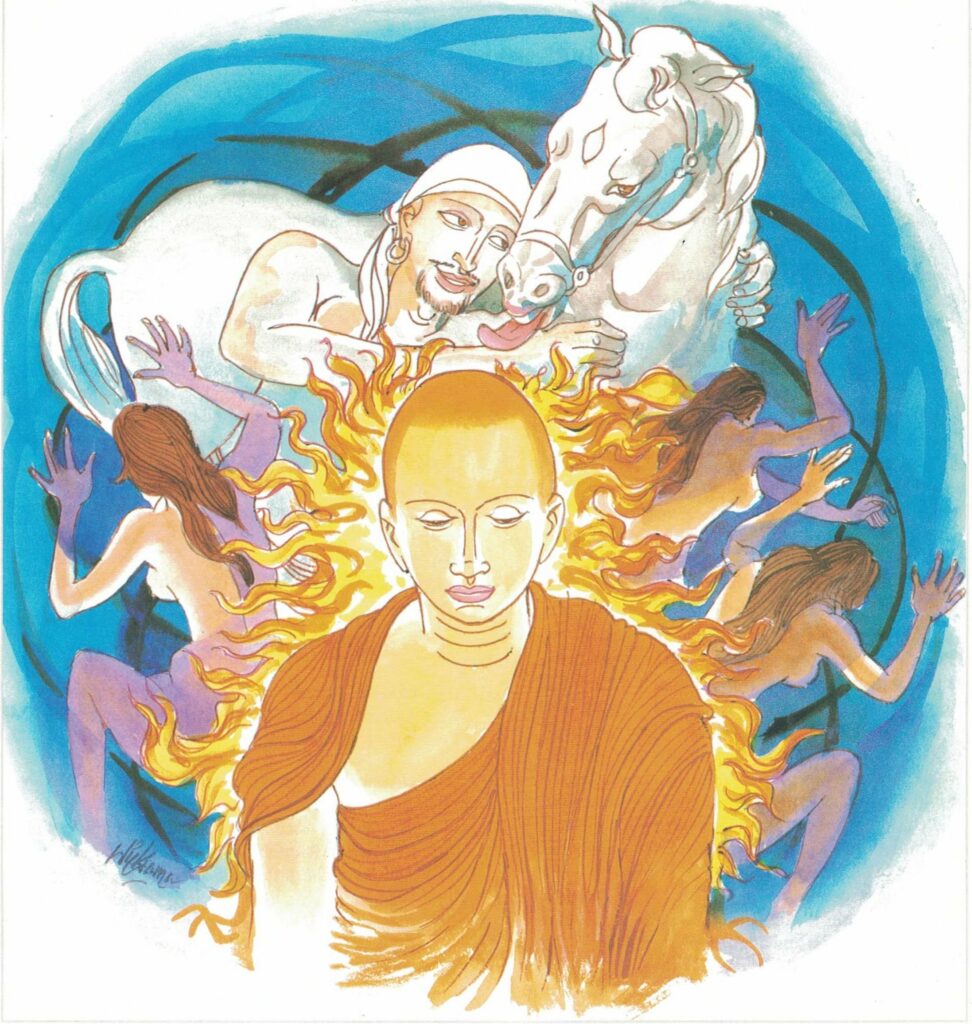

143. Where in the world is found one restrained by shame, awakened out of sleep as splendid horse with whip?

144. As splendid horse touched with whip, be ardent, deeply moved, by faith and virtue, effort too, by meditation, Dhamma’s search, abandon dukkha limitless!

The Story of Venerable Pilotikatissa

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to Venerable Pilotikatissa.

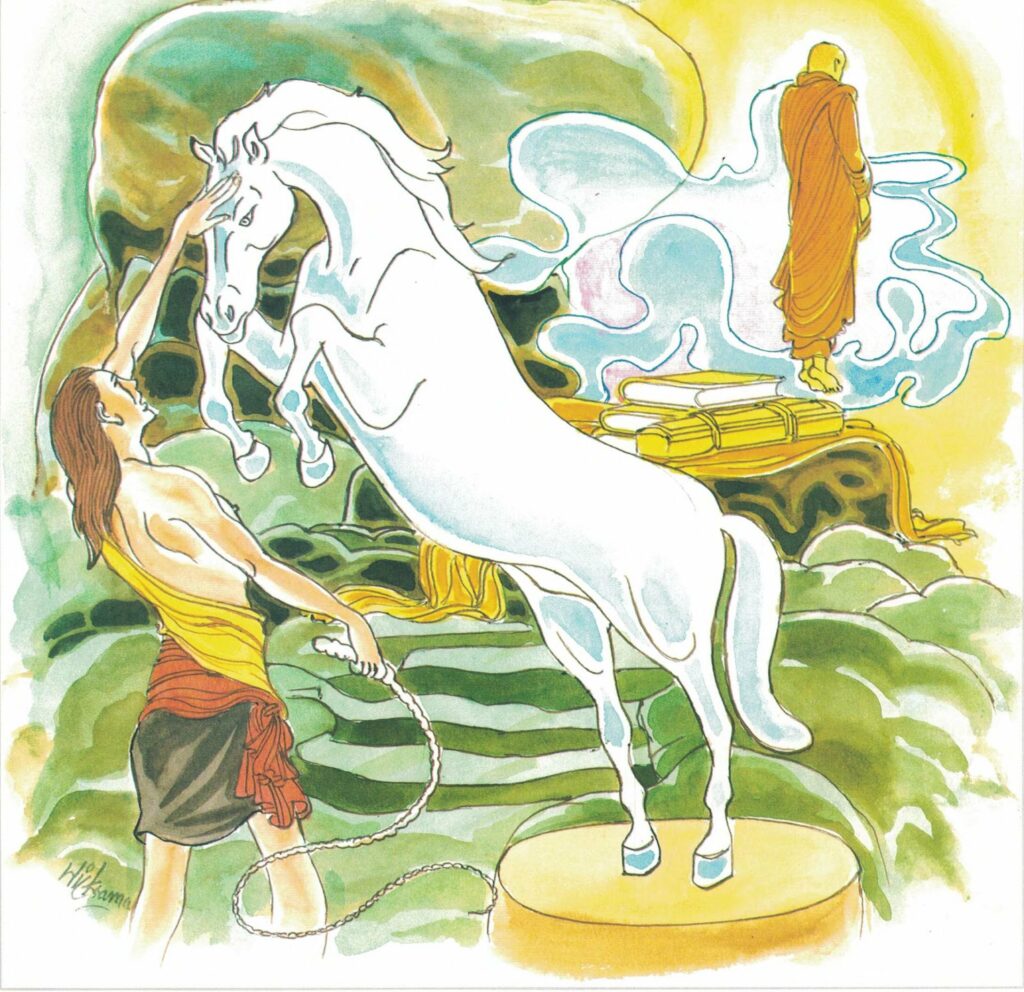

Once, Venerable Ānanda saw a shabbily dressed youth going around begging for food; he felt pity for the youth and made him a sāmanera. The young novice monk left his old clothes and his begging plate on the fork of a tree. When he became a monk he was known as Pilotikatissa. As a monk, he did not have to worry about food and clothing as he was in affluent circumstances. Yet, sometimes he did not feel happy in his life as a monk and thought of going back to the life of a layman. Whenever he had this feeling, he would go back to that tree where he had left his old clothes and his plate. There, at the foot of the tree, he would put this question to himself, “Oh shameless one! Do you want to leave the place where you are fed well and dressed well? Do you still want to put on these shabby clothes and go begging again with this old plate in your hand?” Thus, he would rebuke himself, and after calming down, he would go back to the monastery.

After two or three days, again, he felt like leaving the monastic life of a monk, and again, he went to the tree where he kept his old clothes and his plate. After asking himself the same old question and having been reminded of the wretchedness of his old life, he returned to the monastery. This was repeated many times. When other monks asked him why he often went to the tree where he kept his old clothes and his plate, he told them that he went to see his teacher. Thus keeping his mind on his old clothes as the subject of meditation, he came to realize the true nature of the aggregates of the khandhas, such as anicca, dukkha, anatta, and eventually he became an arahat. Then, he stopped going to the tree. Other monks, noticing that Pilotikatissa had stopped going to the tree where he kept his old clothes and his plate, asked him, “Why don’t you go to your teacher any more?” To them, he answered, ‘When I had the need, I had to go to him; but there is no need for me to go to him now.” When the monks heard his reply, they took him to see the Buddha. When they came to his presence they said, “Venerable! This monk claims that he has attained arahatship; he must be telling lies.” But the Buddha refuted them, and said, “Monks! Pilotikatissa is not telling lies, he speaks the truth. Though he had relationship with his teacher previously, now he has no relationship whatsoever with his teacher. Venerable Pilotikatissa has instructed himself to differentiate right and wrong causes and to discern the true nature of things. He has now become an arahat, and so there is no further connection between him and his teacher.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 143)

bhadro asso kasāṃ iva yo nindaṃ appabodhati

hirī nisedho purisolokasmiṃ koci vijjati

bhadro asso: well bred horse; kasāṃ iva: with the horse whip; yo: if a person; nindaṃ [ninda]: disgrace; appabodhati: avoids;hirī nisedho [nisedha]: gives up evil through shame; puriso [purisa]: such a person; lokasmiṃ koci: rarely in the world; vijjati: is seen

Rare in the world is that person who is restrained by shame. Like a well-bred horse who avoids the whip, he avoids disgrace.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 144)

kasā niviṭṭho bhadro asso yathā ātāpino bhavātha; saṃvegino bhavātha;

saddhāya ca sīlena ca vīriyena ca samādhinā ca dhammavinicchayena ca

sampannavijjācaranā patissatā anappakaṃ idaṃ dukkhaṃ pahassatha

kasā: with the whip; niviṭṭho [niviṭṭha]: controlled; bhadro [bhadra]: well bred;asso: horse; yathā: in what manner; ātāpino [ātāpina]: being penitent; saṃvegino [saṃvegina]: deeply motivated; saddhāya: through devotion; sīlena ca: through discipline; vīriyena ca: and through persistence; samādhinā ca: through mental composure; dhammavinicchayena ca: through examination of experience; sampannavijjācaranā: through the attainment of conscious response; patissatā: through introspection; anappakaṃ [anappaka]: not little; idaṃ dukkhaṃ [dukkha]: this suffering; pahassatha: gets rid of

Like a well-bred horse duly disciplined by the whip, you shall be persistent and earnest. Possessed of devotion, discipline and persistence, and with composure examine experience. Attain to conscious response with well-established introspection.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 143-144)

sīla: virtue. Combined with this extraordinary generosity of a Bodhisatta is his virtuous conduct (sīla). The meaning of the Pāli term is virtue. It consists of duties that one should perform (cāritta) and abstinences which one should practice (vāritta). These duties towards parents, children, husband, wife, teachers, pupils, friends, monks, subordinates, etc., are described in detail in the Sigālovāda Sutta.

The duties of a layman are described in a series of relationships, each, for mnemonic reasons, of five items:

(1) A child should minister to his parents by: (i) supporting them, (ii) doing their duties, (iii) keeping the family lineage, (iv) acting in such a way as to be worthy of his inheritance and furthermore, (v) offering alms in honour of his departed relatives.

(2) Parents, who are thus ministered to by their children, should (i) dissuade them from evil, (ii) persuade them to do good, (iii) teach them an art, (iv) give them in marriage to a suitable wife, and (v) hand over to them their inheritance at the proper time.

(3) A pupil should minister to a teacher by: (i) rising, (ii) attending on him, (iii) attentive hearing, (iv) personal service, and (v) respectfully receiving instructions.

(4) Teachers thus ministered to by pupils should: (i) train them in the best discipline, (ii) make them receive that which is well held by them, (iii) teach them every suitable art and science, (iv) introduce them to their friends and associates, and (v) provide for their safety in every quarter.

(5) A husband should minister to his wife by: (i) courtesy, (ii) not despising her, (iii) faithfulness, (iv) handing over authority to her, and (v) providing her with ornaments.

(6) The wife, who is thus ministered to by her husband, should: (i) perform her duties in perfect order, (ii) be hospitable to the people around, (iii) be faithful, (iv) protect what he brings, and (v) be industrious and not lazy in discharging her duties.

(7) A noble scion should minister to his friends and associates by: (i) generosity, (ii) courteous speech, (iii) promoting their good, (iv) equality, and (v) truthfulness.

(8) The friends and associates, who are thus ministered to by a noble scion, should: (i) protect him when he is heedless, (ii) protect his property when he is heedless, (iii) become a refuge when he is afraid, (iv) not forsake him when in danger, and (v) be considerate towards his progeny.

(9) A master should minister to servants and employees by: (i) assigning them work according to their strength, (ii) supplying them with food and wages, (iii) tending them in sickness, (iv) sharing with them extraordinary delicacies, and (v) relieving them at times.

(10) The servants and employees, who are thus ministered to by their master, should: (i) rise before him, (ii) go to sleep after him, (iii) take only what is given, (iv) perform their duties satisfactorily, and (v) spread his good name and fame.

(11) A noble scion should minister to ascetics and brāhmins by: (i) lovable deeds, (ii) lovable words, (iii) lovable thoughts, (iv) not closing the doors against them, and (v) supplying their material needs.

(12) The ascetics and brāhmins, who are thus ministered to by a noble scion, should: (i) dissuade him from evil, (ii) persuade him to do good, (iii) love him with a kind heart, (iv) make him hear what he has not heard and clarify what he has already heard, and (v) point out the path to a heavenly state.

A Bodhisatta who fulfills all these social duties (cāritta sīla) becomes truly a refined gentleman in the strictest sense of the term. Apart from these duties he endeavours his best to observe the other rules relating to vāritta sīla (abstinence) and thus lead an ideal Buddhist life. Rightly discerning the law of action and consequence, of his own accord, he refrains from evil and does good to the best of his ability. He considers it his duty to be a blessing to himself and others, and not a curse to any, whether man or animal.

As life is precious to all and as no man has the right to take away the life of another, he extends his compassion and loving-kindness towards every living being, even to the tiniest creature that crawls at his feet, and refrains from killing or causing injury to any living creature. It is the animal instinct in man that prompts him mercilessly to kill the weak and feast on their flesh. Whether to appease one’s appetite or as a pastime it is not justifiable to kill or cause a helpless animal to be killed by any method whether cruel or humane. And if it is wrong to kill an animal, what must be said of slaying human beings, however noble the motive may at first sight appear.

Furthermore, a Bodhisatta abstains from all forms of stealing, direct or indirect, and thus develops honesty, trustworthiness and uprightness. Abstaining from misconduct, which debases the exalted nature of man, he tries to be pure and chaste in his sex life. He avoids false speech, harsh language, slander, and frivolous talk and utters only words which are true, sweet, peaceable and helpful. He avoids intoxicating liquors which tend to mental distraction and confusion, and cultivates heedfulness and clarity of vision.

A bodhisatta would adhere to these five principles which tend to control deeds and words, whether against his own interests or not. On a proper occasion he will sacrifice not only possessions and wealth but life itself for the sake of his principles. It should not be understood that a Bodhisatta is perfect in his dealings in the course of his wanderings in saṃsāra. Being a worldling, he possesses his own failings and limitations. Certain jātakas, like the Kānavera Jātaka, depict him as a very desperate highway robber. This, however, is the exception rather than the rule. The great importance attached by an aspirant to Buddhahood to virtue is evident from the Sīlavīmamsa Jātaka where the Bodhisatta says: “Apart from virtue wisdom has no worth.”