Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 63:

yo bālo maññati bālyaṃ paṇaḍito vāpi tena so |

bālo ca paṇḍitamānī sa ve bālo’ti vuccati || 63 ||

63. Conceiving so his foolishness the fool is thereby wise, while ‘fool’ is called that fool conceited that he’s wise.

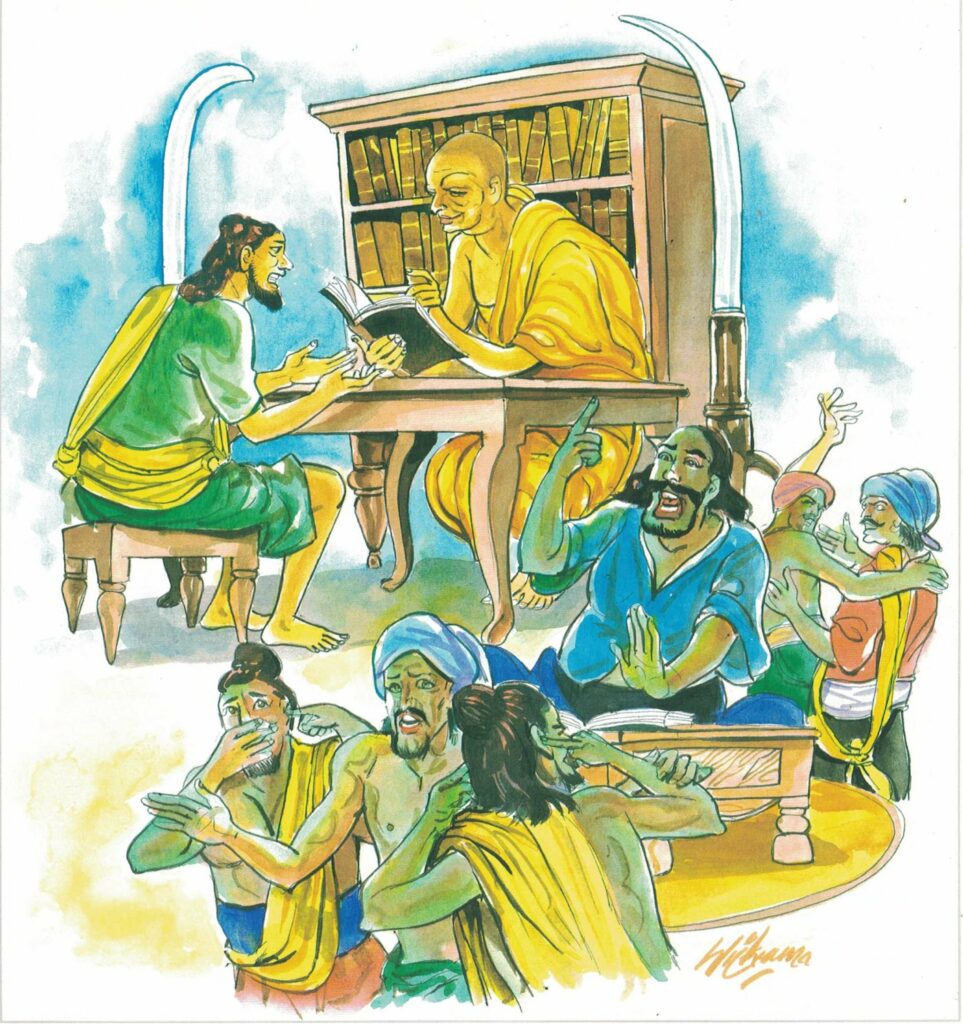

The Story of Two Pick-pockets

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to two pick-pockets.

The story goes that these two men, who were lucky companions, accompanied a great throng to Jetavana to hear the Buddha. One of them listened to the Teaching, the other watched for a chance to steal something. The first, through listening to the Teaching ‘Entered the Stream’; the second found five coins tied to the belt of a certain man and stole the money. The thief had food cooked as usual in his house, but there was no cooking done in the house of his companion. His comrade the thief, and likewise the thief’s wife, ridiculed him, saying, “You are so excessively wise that you cannot obtain money enough to have regular meals cooked in your own house.” He who entered the stream thought to himself, “This man, just because he is a fool, does not think that he is a fool.” And going to Jetavana with his kinsfolk, he told the Buddha of the incident.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 63)

bālo yo bālyaṃ maññati tena so paṇḍito vā api,

bālo ca paṇḍitamānī so ve bālo iti vuccati

bālo [bāla]: a fool; yo bālyaṃ [bālya]: one’s foolishness; maññati: knows;tena: by virtue of that knowledge; so: he; paṇḍito vā api: is also a wise person; bālo ca: if an ignorant person; paṇḍitamānī: thinks he is wise; so: he; ve: in truth; bālo iti vuccati: is called a foolish person

If a foolish individual were to become aware that he is foolish, by virtue of that awareness, he could be described as a wise person. On the other hand, if a foolish person were to think that he is wise, he could be described as a foolish person.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 63)

yo bālo maññati bālyaṃ: if a foolish person knows he is foolish. The implication of this stanza is that the true wisdom is found in the awareness of reality. If one is aware of one’s own foolishness, that awareness makes him wise. The basis of true wisdom is the right knowledge of things as they really are. Those who are foolish but are given to believe that they are wise are truly foolish because that basically false awareness colours the totality of their thinking.

bālo: the foolish person. Foolishness is the result of confusion (moha) and unawareness (avijjā). Unawareness is the primary root of all evil and suffering in the world, veiling man’s mental eyes and preventing him from seeing his own true nature. It carries with it the delusion which tricks beings by making life appear to them as permanent, happy, personal and desirable. It prevents them from seeing that everything in reality is impermanent, liable to suffering, void of ‘I’ and ‘Mine,’ and basically undesirable. Unawareness (avijjā) is defined as “not knowing the four Truths; namely, suffering, its origin, its cessation, and the way to its cessation”.

As avijjā is the foundation of all evil and suffering, it stands first in the formula of Dependent Origination. Avijjā should not be regarded as ‘the causeless cause of all things. It has a cause too. The cause of it is stated thus: ‘With the arising of āsava there is the arising of avijjā. The Buddha said, “No first beginning of avijjā can be perceived, before which avijjā was not, and after which it came to be. But it can be perceived that avijjā has its specific condition.”

As unawareness (avijjā) still exists, even in a very subtle way, until the attainment of Arahatship or perfection, it is counted as the last of the ten Fetters which bind beings to the cycle of rebirths. As the first two Roots of Evil, greed and hate are on their part rooted in unawareness and consequently all unwholesome states of mind are inseparably bound up with it, confusion (moha) is the most obstinate of the three Roots of Evil.

Avijjā is one of the āsavas (influences) that motivate behaviour. It is often called an obscurant but does not appear together with the usual list of five obscurant.

Unawareness (avijjā) of the truth of suffering, its cause, its end, and the way to its end, is the chief cause that sets the cycle of life (saṃsāra) in motion. In other words, it is the not-knowingness of things as they truly are, or of oneself as one really is. It clouds all right understanding.

“Avijjā is the blinding obscurant that keeps us trapped in this cycle of rebirth” says the Buddha. When unawareness is destroyed and turned into awareness, the “chain of causation” is shattered as in the case of the Buddhas and Arahats. In the Itivuttaka the Buddha states “Those who have destroyed avijjā and have broken through the dense darkness of avijjā, will tour no more in saṃsāra.