Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 242-243:

malitthiyā duccaritaṃ maccheraṃ dadato malaṃ |

malā ve pāpakā dhammā asmiṃ loke paramhi ca || 242 ||

tato malā malataraṃ avijjā paramaṃ malaṃ |

etaṃ malaṃ pahatvāna nimmalā hotha bhikkhavo || 243 ||

242. In woman, conduct culpable, with givers, avariciousness, all blemishes these evil things in this world or the next.

243. More basic than these blemishes is ignorance, the worst of all. Abandoning this blemish then, be free of blemish, monks!

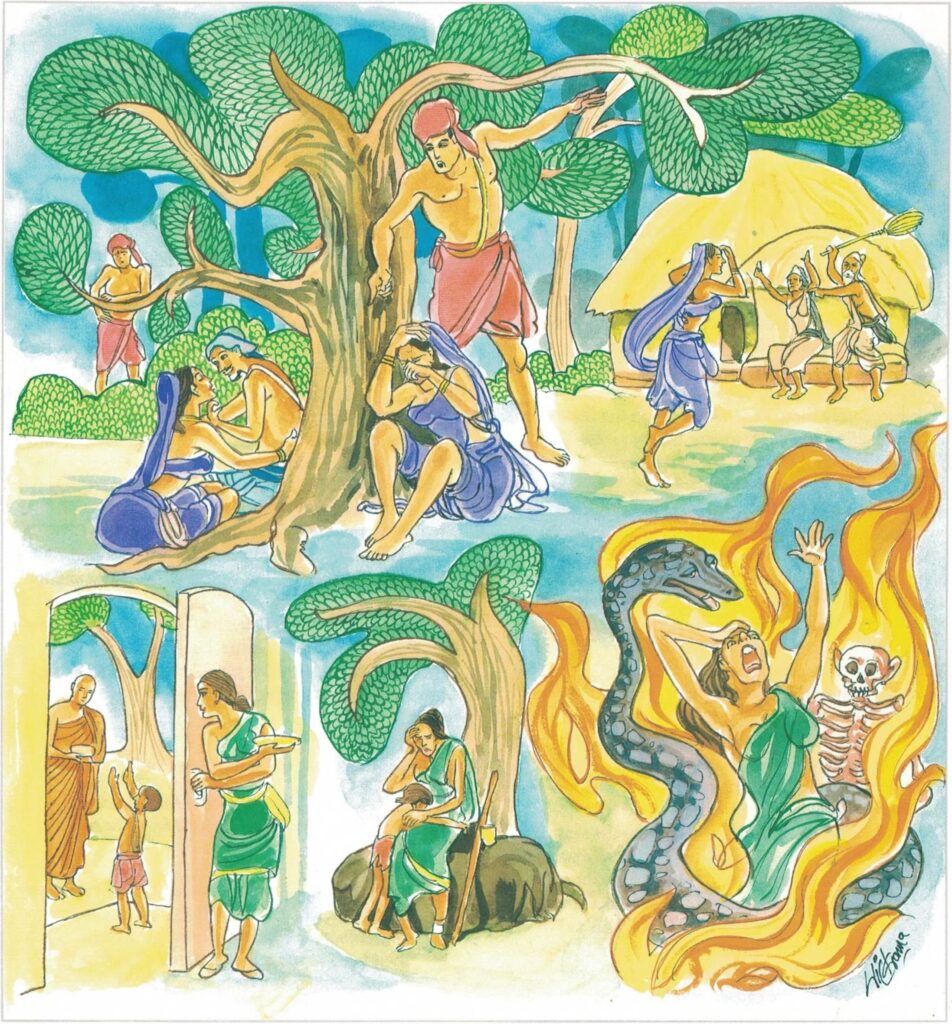

The Story of a Man Whose Wife Committed Adultery

While residing at Veluvana, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to a certain youth of respectable family.

The story goes that this youth married a young woman of equal birth. From the day of her marriage his wife played the adulteress. Embarrassed by her adulteries, the youth had not the courage to meet people face to face. After a few days had passed, it became his duty to wait upon the Buddha. So he approached the Buddha, saluted him, and sat down on one side. “Disciple, why is it that you no longer let yourself be seen?” asked the Buddha. The youth told the Buddha the whole story. Then said the Buddha to him, “Disciple, even in a former state of existence I said, ‘Women are like rivers and the like, and a wise man should not get angry with them.’ But because rebirth is hidden from you, you do not understand this.”

In compliance with a request of the youth, the Buddha related the following Jātaka:

Like a river, a road, a tavern, a hall, a shed,

Such are women of this world: their time is never known.

“For,” said the Buddha, “lewdness is a blemish on a woman; niggardliness is a blemish on the giver of alms; evil deeds, because of the destruction they cause, both in this world and the next, are blemishes on all living beings; but of all blemishes, ignorance is the worst blemish.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 242)

itthiyā duccaritaṃ malaṃ dadato maccheraṃ malaṃ

pāpakā dhammā asmiṃ loke paramhi ca ve malā

itthiyā: to a woman; duccaritaṃ [duccarita]: evil behaviour; malaṃ [mala]: is a blemish; dadato [dadata]: to a giver; maccheraṃ [macchera]: miserliness; malaṃ [mala]: is a blemish; pāpakā dhammā: for evil actions; asmiṃ loke paramhi ca: this world and the next world (are both); ve malā: certainly are blemishes

For women, misconduct is the blemish. For charitable persons, miserliness is the stain. Evil actions are a blemish both here and in the hereafter.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 243)

bhikkhavo, tato malā malataraṃ avijjā paramaṃ

malaṃ etaṃ malaṃ pahatvāna nimmalā hotha

bhikkhavo [bhikkhava]: oh monk: tato malā malataraṃ [malatara]: above all those stains (there is) a worst stain; avijjā: ignorance; paramaṃ malaṃ [mala]: is the worst stain; etaṃ malaṃ [mala]: this stain; pahatvāna: having got rid of; nimmalā hotha: become stainless

O’ Monks, There is a worse blemish than all these stains. The worst stain is ignorance. Getting rid of this stain become stainless–blemishless.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 242-243)

itthiyā duccaritaṃ malaṃ: to a woman evil behaviour is a blemish. the Buddha, of all the contemporary religious leaders, had the most liberal attitude to women. It was also the Buddha who raised the status of women and brought them to a realization of their importance to society. Before the advent of the Buddha, women in India were not held in high esteem. One Indian writer, Hemacandra, looked down upon women as the torch lighting the way to hell–narakamārgadvārasya dīpikā. The Buddha did not humiliate women, but only regarded them as feeble by nature. He saw the innate good of both men and women and assigned to them their due places in His teaching. Sex is no barrier for purification or service.

Sometimes the Pāli term used to connote women is mātugāma which means ‘mother-folk’ or ‘society of mothers’. As a mother, a woman holds an honourable place in Buddhism. The mother is regarded as a convenient ladder to ascend to heaven, and a wife is regarded as the best friend (paramā sakhā) of the husband.

Although at first the Buddha refused to admit women into the Sangha on reasonable grounds, yet later He yielded to the entreaties of Venerable Ānanda and His foster-mother, Mahā Pajāpatī Gotami, and founded the order of bhikkhunīs (nuns). It was the Buddha who thus founded the first society for women with rules and regulations.

Just as arahats Sāriputta and Moggallāna were made the two chief disciples in the Sangha, the oldest democratically constituted celibate Sangha, even so the arahats Khemā and Uppalavannā were made the two chief female disciples in the Order of the Nuns. Many other female disciples, too, were named by the Buddha Himself as amongst most distinguished and pious followers. Amongst the Vajjis, too, freedom to women was regarded as one of the causes that led to their prosperity. Before the advent of the Buddha women did not enjoy sufficient freedom and were deprived of an opportunity to exhibit their innate spiritual capabilities and their mental gifts. In ancient India, as is still seen today, the birth of a daughter to a family was considered an unwelcome and cumbersome addition.

On one occasion while the Buddha was conversing with King Kosala, a messenger came and informed the king that a daughter was born unto him. Hearing it, the king was naturally displeased. But the Buddha comforted and stimulated him, saying, “A woman child, O Lord of men, may prove even better offspring than a male.

To women who were placed under various disabilities before the appearance of the Buddha, the establishment of the Order of Nuns was certainly a blessing. In this Order queens, princesses, daughters of noble families, widows, bereaved mothers, helpless women, courtesans, all despite their caste or rank met on a common footing, enjoyed perfect consolation and peace, and breathed that free atmosphere which was denied to those cloistered in cottages and palatial mansions. Many, who otherwise would have fallen into oblivion, distinguished themselves in various ways and gained their emancipation by seeking refuge in the Sangha.

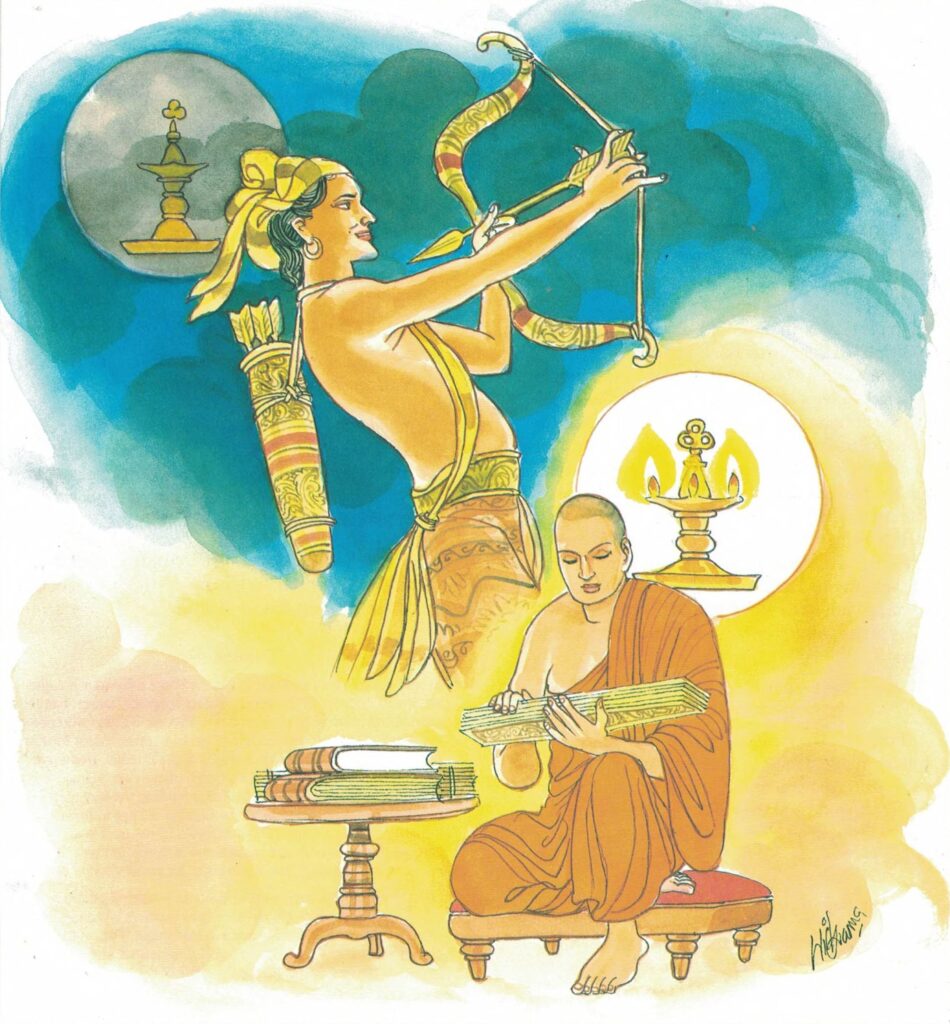

Khemā, the first chief female disciple, was the beautiful consort of King Bimbisāra. She was at first reluctant to see the Buddha as she heard that the Buddha used to refer to external beauty in disparaging terms. One day she paid a casual visit to the monastery merely to enjoy the scenery of the palace. Gradually she was attracted to the hall where the Buddha was preaching. The Buddha, who read her thoughts, created by His psychic powers a handsome young lady, standing aside fanning Him. Khemā admired her beauty. The Buddha made this created image change from youth to middle age and old age, till it finally fell on the ground with broken teeth, grey hair, and wrinkled skin. Then only did she realize the vanity of external beauty and the fleeting nature of life. She thought, “Has such a body come to be wrecked like that? Then so will my body also.”

The Buddha read her mind and said:

They who are slaves to lust drift down the stream,

Like to a spider gliding down the web

He of himself wrought. But the released,

Who all their bonds have snapped in twain,

With thoughts elsewhere intent, forsake the world,

And all delight in sense put far away.

Khemā attained arahatship and with the king’s consent entered the Order. She was ranked foremost in insight amongst the nuns. Patācārā, who lost her two children, husband, parents and brother under very tragic circumstances, was attracted to the Buddha’s presence by His willpower. Hearing the Buddha’s soothing words, she attained the first stage of sainthood and entered the Sangha. One day, as she was washing her feet she noticed how first the water trickled a little way and subsided, the second time it flowed a little further and subsided, and the third time it flowed still further and subsided. “Even so do mortals die,” she pondered, “either in childhood, or in middle age, or when old.” The Buddha read her thoughts and, projecting His image before her, taught her the Dhamma. She attained arahatship and later became a source of consolation to many a bereaved mother.

Dhammadinnā and Bhaddā Kāpilāni were two nuns who were honoured exponents of the Dhamma.

In answer to Māra, the evil one, it was Nun Somā who remarked: “What should the woman-nature count in her who, with mind well-set and knowledge advancing, has right to the Dhamma? To one who entertains doubt with the question ‘Am I a woman in these matters, or am I a man, or what then am I?’–the Evil One is fit to talk.”

Amongst the laity, too, there were many women who were distinguished for their piety, generosity, devotion, learning and loving-kindness.

Visākhā, the chief benefactress of the Order, stands foremost amongst them all. Suppiyā was a very devout lady who, being unable to procure some flesh from the market, cut a piece of flesh from her thigh to prepare a soup for a sick monk.

Nakulamātā was a faithful wife who, by reciting her virtues, rescued her husband from the jaws of death. Sāmāwati was a pious and lovable queen who, without any ill-will, radiated loving-kindness towards her rival even when she was burnt to death through her machination. Queen Mallikā, on many occasions, counselled her husband, King Pasenadi. A maidservant, Khujjuttarā, secured many converts by teaching the Dhamma.

Punabbasumātā was so intent on hearing the Dhamma that she hushed her crying child thus:

O silence, little Uttarā! Be still,

Punabbasu, that I may hear the Norm

Taught by the Master, by the Wisest Man.

Dear unto us is our own child, and dear

Our husband; dearer still than these to me

Is’t of this Doctrine to explore the Path.

A contemplative mother, when questioned why she did not weep at the loss of her only child, said: “Uncalled he hither came, unbidden soon to go; E’en as he came, he went. What cause is here for woe?”

Sumanā and Subhaddā were two sisters of exemplary character who had implicit faith in the Buddha. These few instances will suffice to illustrate the great part played by women in the time of the Buddha especially under the guidance of the Buddha.