Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 411:

yassā’layā na vijjanti aññāya akathaṃkathī |

amatogadhaṃ anuppattaṃ tam ahaṃ brūmi brāhmaṇaṃ || 411 ||

411. In whom is no dependence found, with Final Knowledge freed from doubt, who’s plunged into the Deathless depths, that one I call a Brahmin True.

The Story of Venerable Mahā Moggallāna

This religious instruction was given by the Buddha while he was in residence at Jetavana Monastery, with reference to Venerable Mahā Moggallāna.

This story is similar to the preceding, except that on this occasion the Buddha, perceiving that Venerable Mahā Moggallāna was free from craving, gave this verse.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 411)

yassa ālayā na vijjanti aññāya akathaṃkathī

amatogadhaṃ anuppattaṃ taṃ ahaṃ brāhmaṇaṃ brūmi

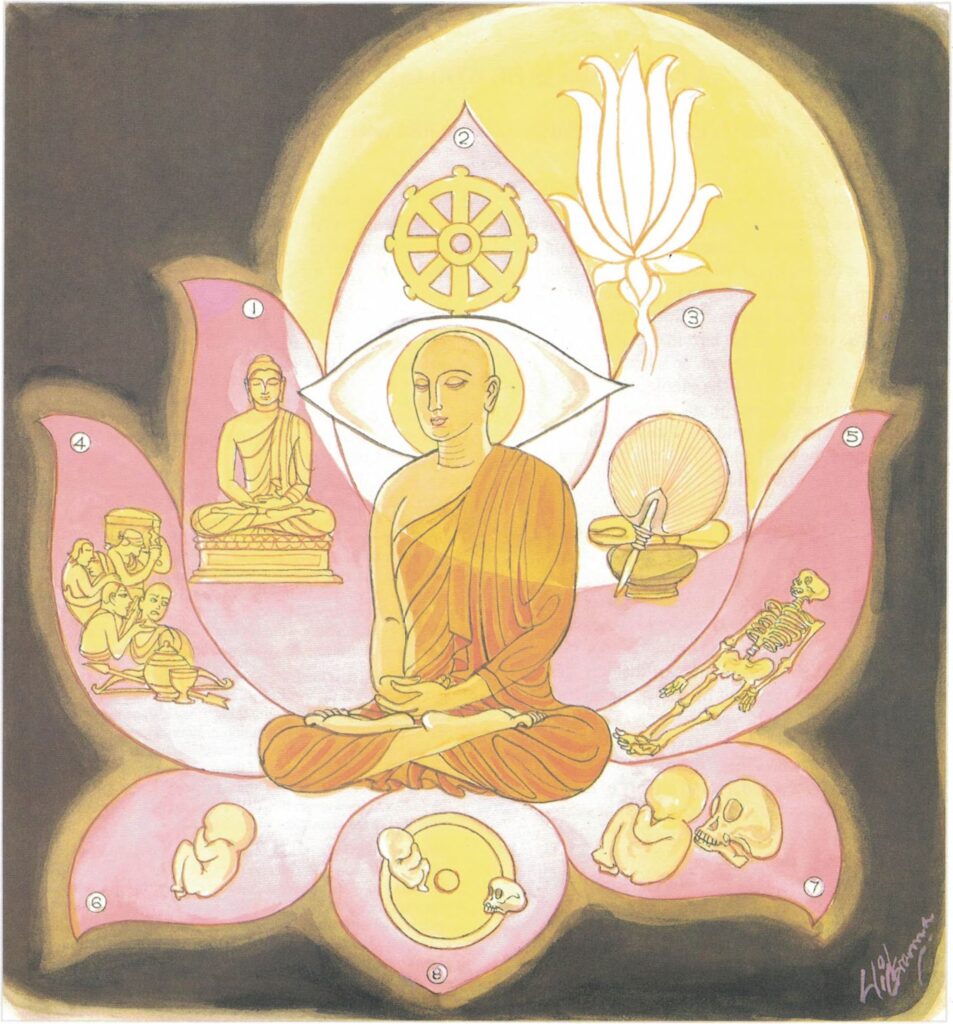

yassa: if in someone; ālayā: attachments; na vijjanti: are not seen; aññāya: due to right awareness; akathaṃkathī: if he has no doubts; amatogadhaṃ [amatogadha]: the flood of the Deathless–Nibbāna; anuppattaṃ [anuppatta]: who has reached; taṃ: him; ahaṃ: I; brāhmaṇaṃ brūmi: describe a brāhmaṇa

He has no attachments–no attachments can be discovered in him. He has no spiritual doubts due to his right awareness. He has entered the deathless–Nibbāna. I describe him as a true brāhmaṇa.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 411)

The story of Venerable Mahā Moggallāna: If Sāriputta could be regarded as the Chief Disciple on the right of Buddha, Moggallāna was the Chief Disciple on His left. They were born on the same day and were associated with each other during many previous lives; so were they during the last life.

Venerable Mahā Moggallāna was foremost in the noble Sangha for the performance of psychic feats.

Once, a king of cobras called Nandopananda, also noted for psychic feats, was threatening all beings of the Himālayas that should happen to pass that way.

The Buddha was besieged with offers from various members of the noble Sangha to subdue the snake king. At last, Venerable Mahā Moggallāna’s turn came and the Buddha readily assented. He knew the monk was equal to the task. The result was a Himālayan encounter when the nāga king, having been worsted in the combat, sued for peace. The Buddha was present throughout and cautioned Moggallāna. The epic feat was succinctly commemorated in the seventh verse of the Jayamangala Gātha which is recited at almost every Buddhist occasion.

Whether in shaking the marble palace of Sakka the heavenly ruler, by his great toe or visiting hell, he was equally at ease. These visits enabled him to collect all sorts of information. He could graphically narrate to dwellers of this Earth the fate of their erstwhile friends or relatives; how, by evil kamma, some get an ignominious re-birth in hell and others, by good kamma, an auspicious re-birth in one of the six heavens. These ministrations brought great kudos to the Dispensation, much to the chagrin of other sects. His life is an example and a grim warning. Even a chief disciple, capable of such heroic feats, was not immune from the residue of evil kamma, though sown in the very remote past.

In the last life of Moggallāna, he could not escape the relentless force of kamma. For, with an arahat’s parinirvāna, good or bad effects of kamma come to an end. He was trapped twice by robbers but he made good his escape. But on the third occasion, he saw, with his divine eye, the futility of escape. He was mercilessly beaten so much so that his body could be put even in a sack. But death must await his destiny. It is written that a chief disciple must not only predecease the Buddha but must also repair to the Buddha before his death (parinibbāna) and perform miraculous feats and utter verses in farewell, and the Buddha had to enumerate his virtues in return. He was no exception.