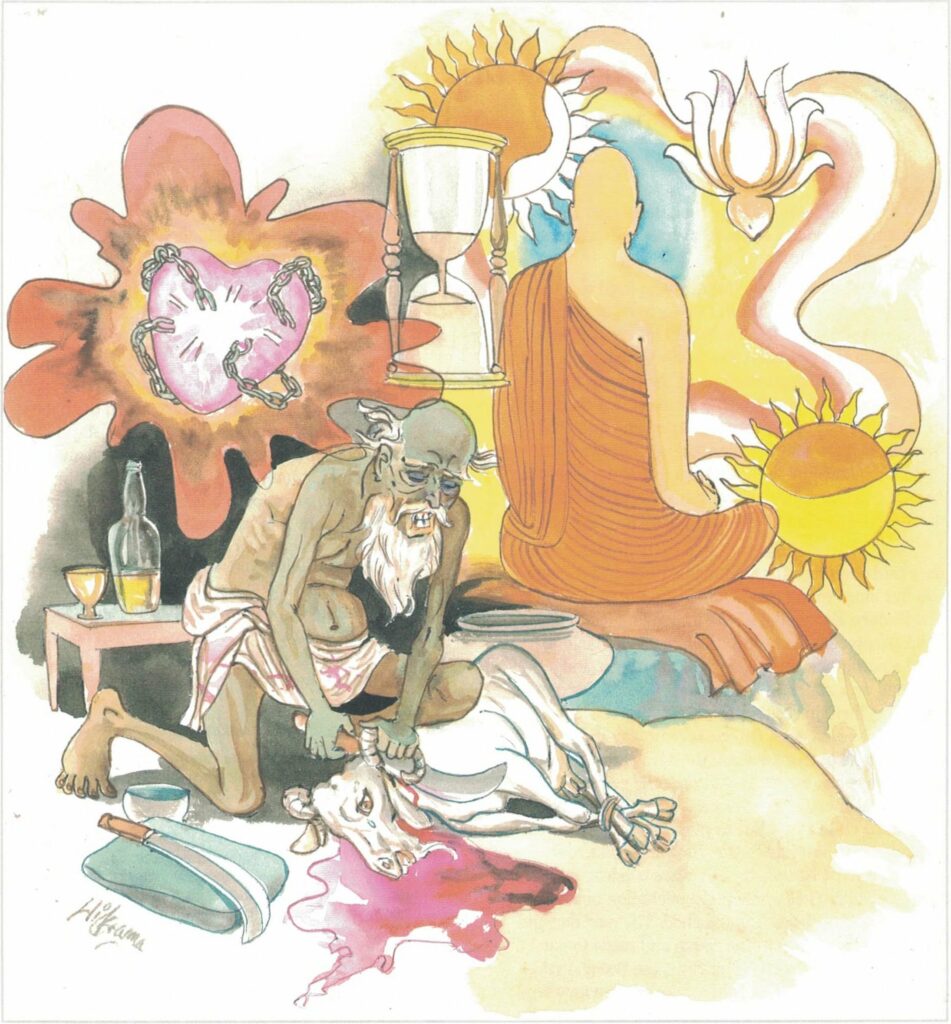

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 110:

yo ca vassasataṃ jīve dussīlo asamāhito |

ekāhaṃ jīvitaṃ seyyo sīlavantassa jhāyino || 110 ||

110. Though one should live a hundred years foolish, uncontrolled, yet better is life for a single day moral and meditative.

The Story of Novice Monk Saṃkicca

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to novice monk Saṃkicca.

On one occasion, thirty monks each took a meditation topic from the Buddha and left for a large village, one hundred and twenty yojanas (leagues) away from Sāvatthi. At that time, five hundred robbers were staying in a thick jungle, and they wanted to make an offering of human flesh and blood to the guardian spirits of the forest. So they came to the village monastery and demanded that one of the monks be given up to them for sacrifice to the guardian spirits. From the eldest to the youngest, each one of the monks volunteered to go. With the monks, there was also a young novice monk by the name of Saṃkicca, who was sent along with them by Venerable Sāriputta. This novice monk was only seven years old, but had already attained arahatship. Saṃkicca said that Venerable Sāriputta, his teacher, knowing this danger in advance, had purposely sent him to accompany the monks, and that he should be the one to go with the robbers. So saying, he went along with the robbers. The monks felt very bad for having let the young novice monk go. The robbers made preparations for the sacrifice; when everything was ready, their leader came to the young novice monk, who was then seated, with his mind fixed on jhāna concentration. The leader of the robbers lifted his sword and struck hard at the young novice monk, but the blade of the sword curled up without cutting the flesh. He straightened up the blade and struck again; this time, it bent upwards right up to the hilt without harming the novice monk. Seeing this strange happening, the leader of the robbers dropped his sword, knelt at the feet of the novice monk and asked his pardon. All the five hundred robbers were amazed and terror-stricken; they repented and asked permission from Saṃkicca to become monks. He complied with their request.

Having so done, he established them in the ten precepts, and taking them with him, set out. So with a retinue of five hundred monks he went to their place of residence. When they saw him, they were relieved in mind.

Then Saṃkicca and the five hundred monks continued on their way to pay respect to Venerable Sāriputta, his teacher, at the Jetavana Monastery. After seeing Venerable Sāriputta they went to pay homage to the Buddha. When told what had happened, the Buddha said, “Monks, if you rob or steal and commit all sorts of evil deeds, your life would be useless, even if you were to live a hundred years. Living a virtuous life even for a single day is much better than a hundred years of a life of depravity.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 110)

dussīlo asamāhito yo ca vassasataṃ jīve

sīlavantassa jhāino ekāhaṃ jīvitaṃ seyyo

dussīlo [dussīla]: a person who is bereft of virtue; asamāhito [asamāhita]: uncomposed in mind; yo: that one; ca: even if; vassasataṃ [vassasata]: hundred years; jīve: were to live; sīlavantassa: of the virtuous; jhāino [jhāina]: who is meditative; ekāhaṃ [ekāha]: only one day’s; jīvitaṃ [jīvita]: living; seyyo [seyya]: is great

A single day lived as a virtuous meditative person is greater than a hundred years of life as an individual bereft of virtue and uncomposed in mind.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 110)

jhāino: one who practises jhāna (meditation). Jhāna–(mental repose) refers to the four meditative levels of mental repose of the “sphere of form”. They are attained through a process of mental purification during which there is a gradual, though temporary, calming down of five-fold sense-activity and of the Five Obscurants (emotional disturbances that cloud the mind). The state of mind, however, is one of full alertness and lucidity. This high degree of tranquillity is generally developed by the practice of one or more of the forty subjects of Tranquillity Meditation. There are also the four formless levels of tranquillity called ‘formless spheres’ (arūpa āyatana).