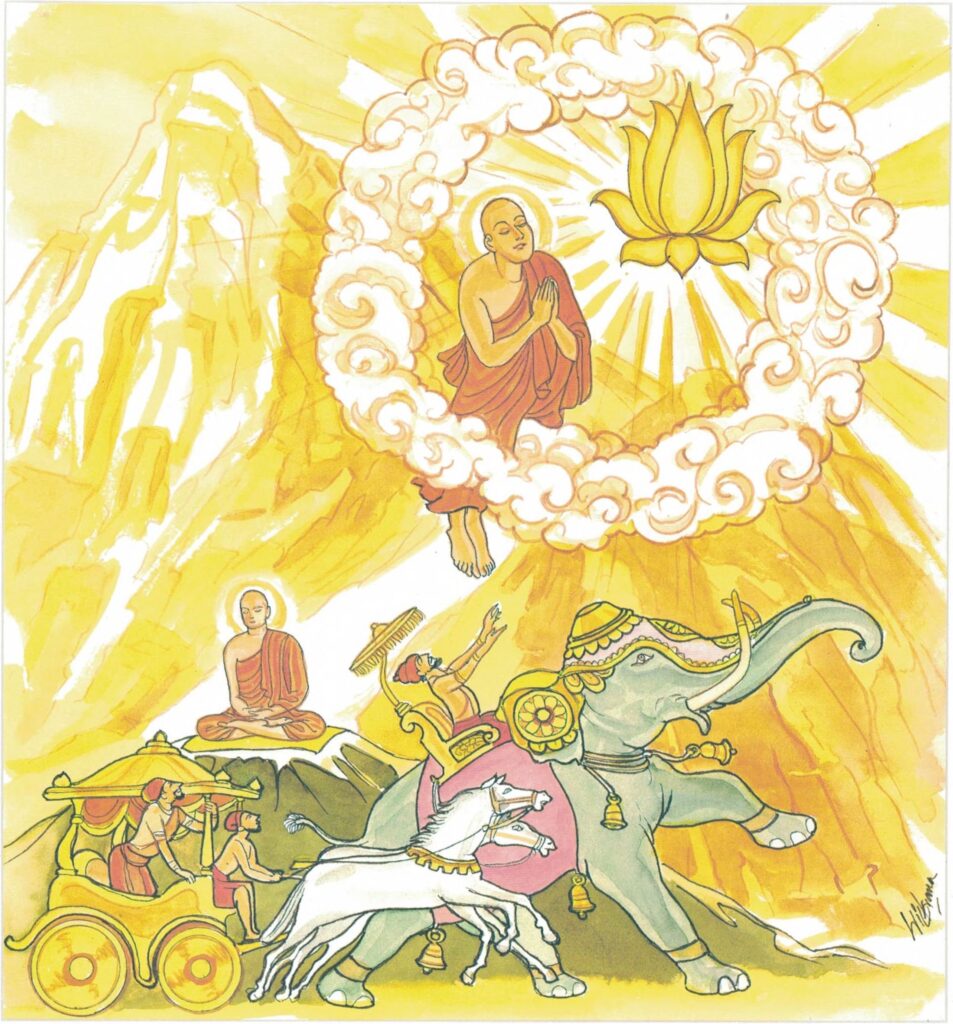

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 323:

nahi etehi yānehi gaccheyya agataṃ disaṃ |

yathā’ttanā sudantena danto dantena gacchati || 323 ||

323. Surely not on mounts like these one goes the Unfrequented Way as one by self well-tamed is tamed and by the taming goes.

The Story of the Monk Who Had Been A Trainer of Elephants

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse with reference to a monk who had previously been an elephant trainer.

On one occasion, some monks saw an elephant trainer and his elephant on the bank of the river Aciravati. As the trainer was finding it difficult to control the elephant, one of the monks, who was an ex-elephant trainer, told the other monks how it could be easily handled. The elephant trainer, hearing him, did as was told by the monk, and the elephant was quickly subdued. Back at the monastery, the monks related the incident to the Buddha. The Buddha called the ex-elephant trainer monk to him and said. “O vain bhikkhu, who is yet far away from magga and phala! You do not gain anything by taming elephants. There is no one who can get to a place where one has never been before (i.e., Nibbāna) by taming elephants; only one who has tamed himself can get there.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 323)

danto dantena sudantena attanā agataṃ disaṃ

yathā gacchati etehi yānehi nahi gaccheyya

danto [danta]: the disciplined person; dantena: due to the discipline; sudantena: well disciplined; attanā: mind; agataṃ [agata]: not gone before; disaṃ [disa]: region; yathā: in such a way; gacchati: goes; etehi yānehi: these vehicles; nahi gaccheyya: cannot go

Indeed, not by any means of transport (such as elephants and horses) can one go to the place one has never been before, but by thoroughly taming oneself, the tamed one can get to that place–Nibbāna.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 323)

This stanza typifies the Buddha’s attitude towards his pupils and towards the world at large. He insisted that each person must strive for his own salvation.

The Buddha disapproved of those who professed to have secret doctrines, saying: Secrecy is the hallmark of false doctrine. Addressing the Venerable Ānanda, his personal attendant, the Buddha said, “I have taught the Dhamma, Ānanda, without making any distinction between exoteric and esoteric doctrine, for in respect of the truth, Ānanda, the Buddha has no such thing as the closed fist of a teacher, who hides some essential knowledge from the pupil. He declared the Dhamma freely and equally to all. He kept nothing back, and never wished to extract from his disciples blind and submissive faith in him and his teaching. He insisted on discriminative examination and intelligent enquiry. In no uncertain terms did he urge critical investigation when he addressed the inquiring Kālāmas in a discourse that has been rightly called ‘the first charter of free thought.’”

To take anything on trust is not in the spirit of Buddhism, so we find this dialogue between the Buddha and his disciples:

—If, now, knowing this and preserving this, would you say: ‘We honour our Master and through respect for him we respect what he teaches?’

—No. Venerable.

—That which you affirm, O’ disciples, is it not only that which you yourselves have recognized, seen and grasped?

—Yes, Venerable.

And in conformity with this thoroughly correct attitude of true enquiry, it is said, in a Buddhist treatise on logic: ‘As the wise test gold by burning, by cutting it and rubbing it (on a touchstone), so are you to accept my words after examining them and not merely out of regard for me.’

Buddhism is free from compulsion and coercion and does not demand of the follower blind faith. At the very outset the skeptic will be pleased to hear of its call for investigation. Buddhism, from beginning to end, is open to all those who have eyes to see and mind to understand.