Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 302:

duppabbajjaṃ durabhiramaṃ durāvāsā gharā dukhā |

dukkho’samānasaṃvāso dukkhānupatitaddhagu |

tasmā na c’addhagu siyā na ca dukkhānupatito siyā || 302 ||

302. Hard’s the going forth, hard to delight in it, hard’s the household life and dukkha is it too, Dukkha’s to dwell with those dissimilar and dukkha befalls the wanderer. Be therefore not a wanderer, not one to whom dukkha befalls.

The Story of the Monk from the Country of the Vajjis

While residing at the Veluvana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse with reference to a monk from Vesāli, a city in the country of the Vajjis.

On the night of the full moon day of Kattika, the people of Vesāli celebrated the festival of the constellations (nakkhatta) on a grand scale. The whole city was lit up, and there was much merry-making with singing, dancing, etc. As he looked towards the city, standing alone in the monastery, the monk felt lonely and dissatisfied with his lot. Softly, he murmured to himself, “There can be no one whose lot is worse than mine.” At that instant, the spirit guarding the woods appeared to him, and said, “Those beings in niraya envy the lot of the beings in the deva world; so also, people envy the lot of those who live alone in the woods.” Hearing those words, the monk realized the truth of those words and he regretted that he had thought so little of the lot of a monk.

Early in the morning the next day, the monk went to the Buddha and reported the matter to him. In reply, the Buddha told him about the hardships in the life of all beings. Then the Buddha pronounced this stanza.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 302)

duppabbajjaṃ durabhiramaṃ gharā durāvāsā

dukkhā asamānasamvāso dukkho addhagū

dukkhānupatito tasmā addhagū na ca siyā

dukkhānupatito na ca siyā duppabbajjaṃ [duppabbajja]: being a monk is difficult; durabhiramaṃ [durabhirama]: difficult it is to take delight in that life; gharā: households; durāvāsā: are difficult to live in; dukkhā: painful; asamānasamvāso [asamānasamvāsa]: living with those who have desperate views; dukkho [dukkha]: is painful; addhagū: a person who has stepped into the path of saṃsāra; dukkhānupatito [dukkhānupatita]: are pursued by suffering; tasmā: therefore; addhagū: a saṃsāra traveller; na ca siyā: one should not become; dukkhānupatito [dukkhānupatita]: one pursued by suffering; na ca siyā: one should not become

It is hard to become a monk; it is hard to be happy in the practice of a monk. The hard life of a householder is painful; to live with those of a different temperament is painful. A traveller in saṃsāra is continually subject to dukkha; therefore, do not be a traveller in saṃsāra; do not be the one to be repeatedly subject to dukkha.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 302)

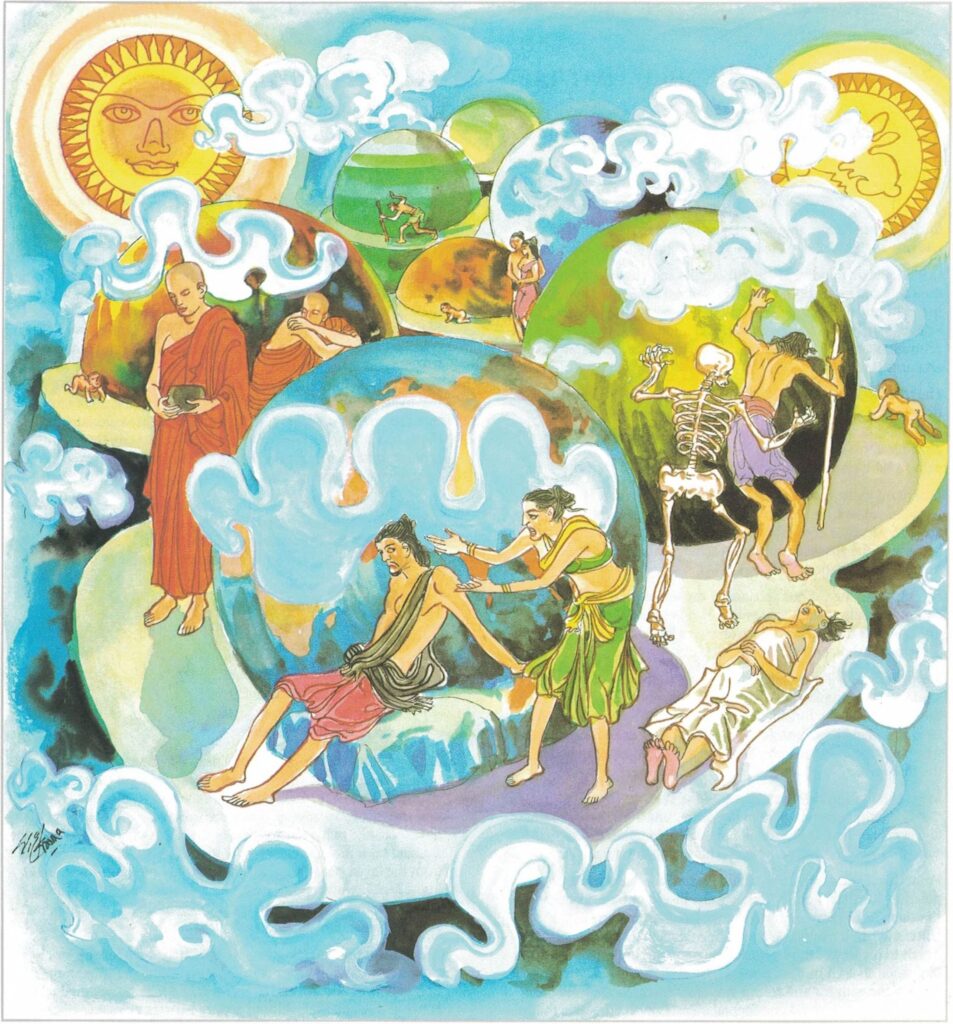

saṃsāra: round of rebirth, lit. perpetual wandering. Saṃsāra is a name by which is designated the sea of life, ever restlessly heaving up and down, the symbol of this continuous process of ever and again being born, growing old, suffering and dying. More precisely put, saṃsāra is the unbroken chain of the five-fold khanda-combinations, which, constantly changing from moment to moment, follow continuously one upon the other through inconceivable periods of time. Of this saṃsāra, a single lifetime constitutes only a tiny and fleeting fraction; hence to be able to comprehend the first noble truth of universal suffering, one must let one’s gaze rest upon the saṃsāra, upon this frightful chain of rebirths, and not merely upon one single lifetime, which of course, may sometimes be less painful.

The Buddha said: O’ monks, this cycle of continuity (saṃsāra) is without a visible end, and the first beginning of beings wandering and running around, enveloped in ignorance (avijjā) and bound down by the fetters of thirst (desire, taṇhā) is not to be perceived….

And further, referring to ignorance which is the main cause of the continuity of life the Buddha said: The first beginning of ignorance (avijjā) is not to be perceived in such a way as to postulate that there was no ignorance beyond a certain point.

Thus, it is not possible to say that there was no life beyond a certain definite point.