Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 259:

na tāvatā dhammadharā yāvatā bahu bhāsati |

yo ca appam’pi sutvāna dhammaṃ kāyena passati |

sa ve dhammadharo hoti yo dhammaṃ nappamajjati || 259 ||

259. Just because articulate one’s not skilled in Dhamma; but one who’s heard even little and Dhamma in the body sees, that one is skilled indeed, not heedless of the Dhamma.

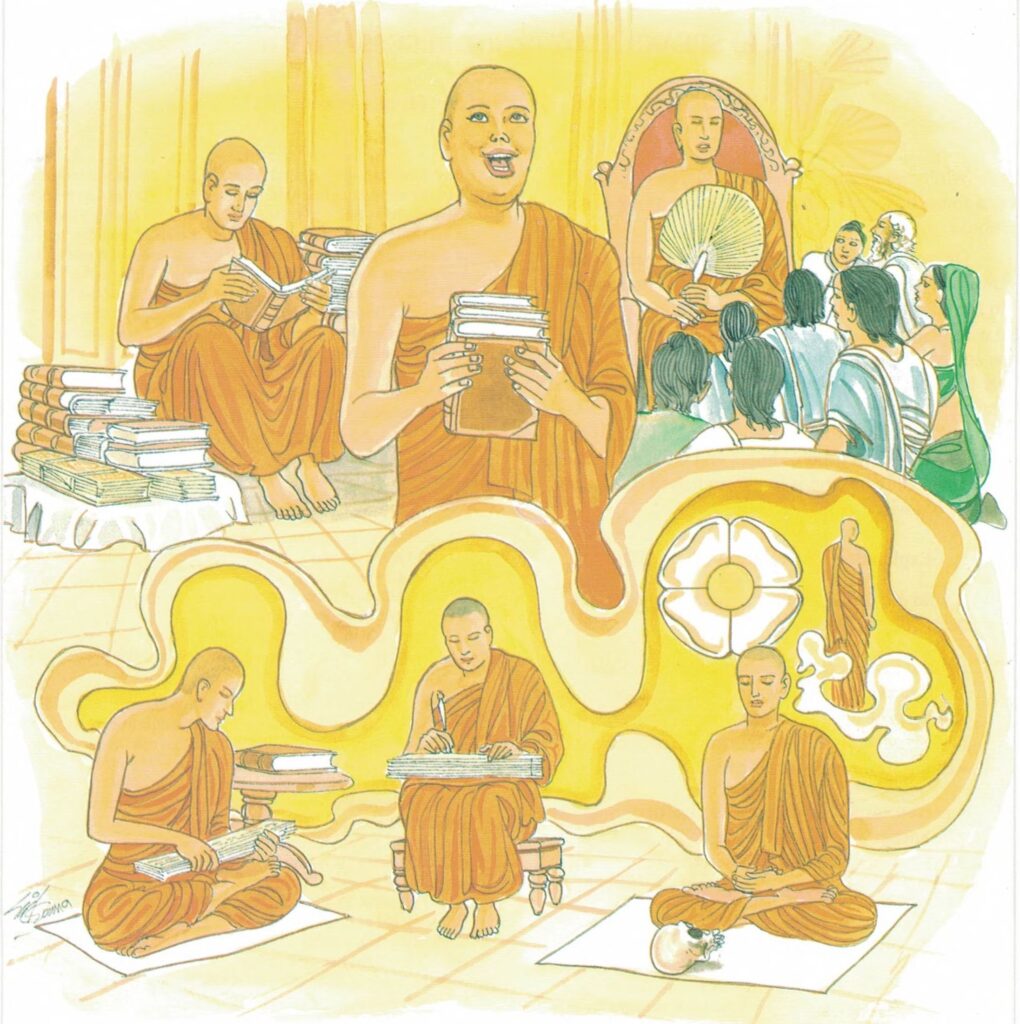

The Story of Ekūdāna the Arahat

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse with reference to a monk who was an arahat.

This monk lived in a grove near Sāvatthi. He was known as Ekūdāna, because he knew only one stanza of exultation (udāna) by heart:

To the monk of lofty thoughts, heedful, training himself in the ways of silence, To such a monk, tranquil and ever mindful, sorrows come not.

But the monk fully understood the meaning of the Dhamma as conveyed by the stanza. On each sabbath day, he would exhort others to listen to the Dhamma, and he himself would recite the one stanza he knew. Every time he had finished his recitation, the guardian spirits (devās) of the forests praised him and applauded him resoundingly. On one fast-day, two learned elder monks, who were well-versed in the Tipitaka, accompanied by five hundred monks came to his place. Ekūdāna asked the two elder monks to preach the Dhamma. They enquired if there were many who wished to listen to the Dhamma in this out of the way place. Ekūdāna answered in the affirmative and also told them that even the guardian spirits of the forests usually came, and that they usually praised and applauded at the end of discourses. So, the two learned elders took turns to preach the Dhamma, but when their discourses ended, there was no applause from the guardian spirits of the forests. The two learned theras were puzzled; they even doubted the words of Ekūdāna. But Ekūdāna insisted that the guardian spirits used to come and always applauded at the end of each discourse. The two elders then pressed Ekūdāna to do the preaching himself.

Ekūdāna held the fan in front of him and recited the usual stanza. At the end of the recitation, the guardian spirits applauded as usual. The monks who had accompanied the two learned elders complained that the devas inhabiting the forests were very partial.

They reported the matter to the Buddha on arrival at the Jetavana Monastery. To them the Buddha said, “Monks! I do not say that a monk who has learnt much and talks much of the Dhamma is “one who is versed in the Dhamma, (Dhammadhara).” One who has learnt very little and knows only one stanza of the Dhamma, but fully comprehends the Four Noble Truths, and is ever mindful is the one who is truly versed in the Dhamma.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 259)

yāvatā bahu bhāsati, tāvatā dhammadharo na

yo ca appaṃ api sutvāna kāyena dhammaṃ passati,

so ve dhammadharo hoti so dhammaṃ nappamajjati.

yāvatā: just because; bahu bhāsati: one speaks a lot; tāvatā: by that; dhammadharo na: one does not become an upholder of the dhamma; yo ca: if someone; appaṃ api: even a little of the dhamma; sutvāna: having heard; kāyena: by his body; dhammaṃ passati: practices the dhamma; so: he; ve: without any doubt; dhammadharo hoti: becomes an upholder of dhamma; yo: if someone; dhammaṃ [dhamma]: in dhamma; nappamajjati: is diligent (he too is an upholder of dhamma)

One does not become an upholder of the Law of Righteousness merely because one talks quite a lot. Even if one, though he has heard only a little, experiences the Dhamma by his body and is diligent, he is truly an upholder of the Dhamma.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 259)

bahu bhāsati: speaks uninhibitedly. The tendency to speak effusively can be counteracted by the silence of the mind. The means to achieve this is meditation. Watching the mind in meditation, and allowing the mind to be silent can be effected through the contemplation of the mind (citta vipassanā).

But how does one dwell in contemplation of the mind? Herein the disciple knows the greedy mind as greedy, and the mind which is not greedy as not greedy; knows the angry mind as angry, and the not angry mind as not angry; knows the deluded mind as deluded, and the undeluded mind as undeluded. He knows the cramped mind as cramped, and the scattered mind as scattered; knows the developed mind as developed, and the undeveloped mind as undeveloped; knows the surpassable mind as surpassable, and the unsurpassable mind as unsurpassable; knows the concentrated mind as concentrated, and the unconcentrated mind as unconcentrated; knows the freed mind as freed, and the unfreed mind as unfreed.

Thus he dwells in contemplation of the mind, either with regard to his own person, or to other persons, or to both. He beholds how the mind arises; beholds how it passes away; beholds the arising and passing away of the mind. ‘Mind is there’: this clear awareness is present in him, to the extent necessary for knowledge and mindfulness; and he lives independent, unattached to anything in the world. Thus does the disciple dwell in contemplation of the mind.