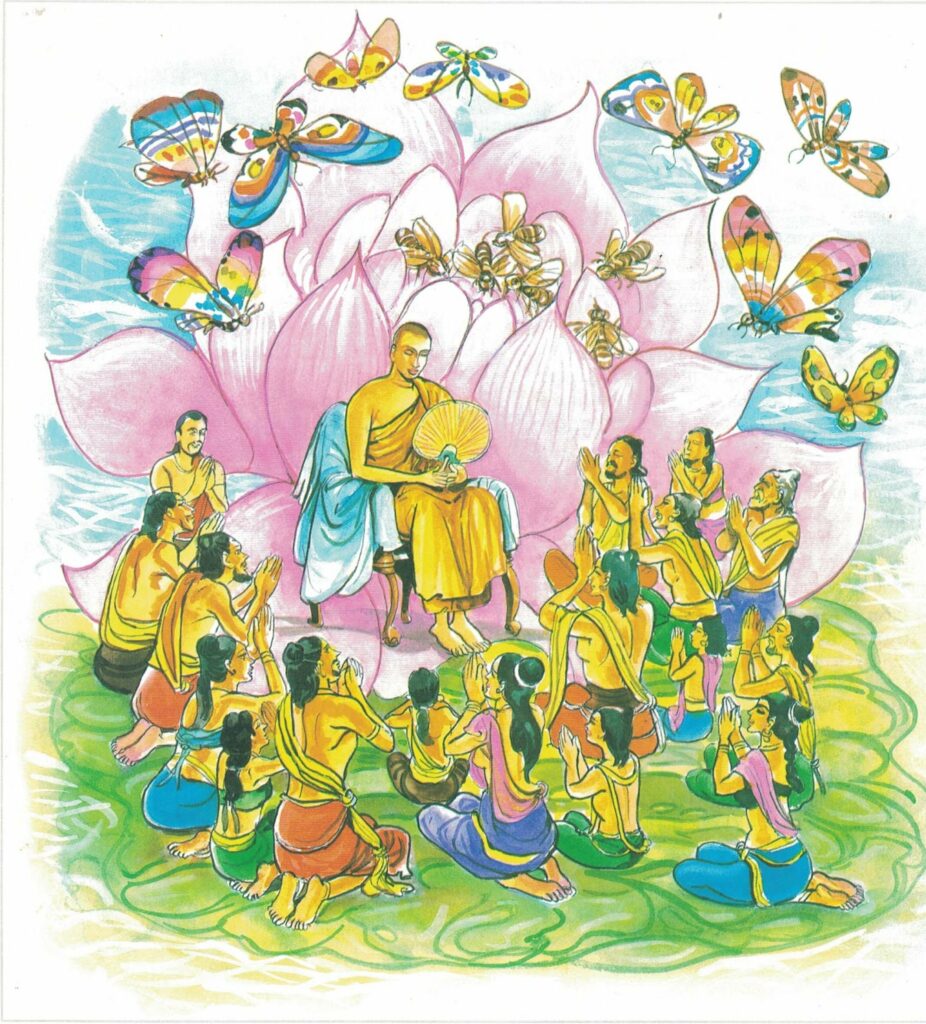

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 51-52:

yathāpi ruciraṃ pupphaṃ vaṇṇavantaṃ agandhakaṃ |

evaṃ subhāsitā vācā aphalā hoti akubbato || 51 ||

yathāpi ruciraṃ pupphaṃ vaṇṇavantaṃ sagandhakaṃ |

evaṃ subhāsitā vācā saphalā hoti pakubbato || 52 ||

51. Just as a gorgeous blossom brilliant but unscented, so fruitless the well-spoken words of one who does not act.

52. Just as a gorgeous blossom brilliant and sweet-scented, so fruitful the well-spoken words of one who acts as well.

The Story of Chattapāni, a Lay Disciple

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these Verses, with reference to the lay disciple Chattapāni and the two queens of King Pasenadi of Kosala. At Sāvatthi lived a lay disciple named Chattapāni, versed in the Tripitaka, enjoying the fruit of the second path. Early one morning, in observance of fasting, he went to pay his respects to the Buddha. For those who enjoy the fruition of the second path and those who are noble disciples, by reason of their previous undertaking, they do not take upon themselves the obligations of fast-day. Such persons, solely by virtue of the Path, lead the holy life and eat but one meal a day. Therefore said the Buddha, “Great king, Ghaṭīkāra the potter eats but one meal a day, leads the holy life, is virtuous and upright.” Thus, as a matter of course, those who enjoy the fruition of the second path eat but one meal a day and lead the holy life.

Chattapāni also, thus observing the fast, approached the Buddha, paid obeisance to him, and sat down and listened to the Dhamma. Now at this time King Pasenadi Kosala also came to pay his respects to the Buddha. When Chattapāni saw him coming, he reflected, “Shall I rise to meet him or not?” He came to the following conclusion, “Since I am seated in the presence of the Buddha, I am not called upon to rise on seeing the king of one of his provinces. Even if he becomes angry, I will not rise. For if I rise on seeing the king, the king will be honoured, and not the Buddha. Therefore I will not rise.” Therefore Chattapāni did not rise. (Wise men never become angry when they see a man remain seated, instead of rising, in the presence of those of higher rank.)

But when King Pasenadi saw that Chattapāni did not rise, his heart was filled with anger. However, he paid obeisance to the Buddha and sat down respectfully on one side. The Buddha, observing that he was angry, said to him, “Great king, this lay disciple Chattapāni is a wise man, knows the Dhamma, is versed in the Tripitaka, is contented both in prosperity and adversity.” Thus did the Buddha extol the lay disciple’s good qualities. As the king listened to the Buddha’s praise of the lay disciple, his heart softened.

Now one day after breakfast, as the king stood on the upper floor of his palace, he saw the lay disciple Chattapāni pass through the courtyard of the royal palace with a parasol in his hand and sandals on his feet. Straightaway he caused him to be summoned before him. Chattapāni laid aside his parasol and sandals, approached the king, paid obeisance to him, and took his stand respectfully on one side. Said the king to Chattapāni, “Lay disciple, why did you lay aside your parasol and sandals?” “When I heard the words, ‘The king summons you,’ I laid aside my parasol and sandals before coming into his presence.” “Evidently, then, you have today learned that I am king.” “I always knew that you were king.” “If that be true, then why was it that the other day, when you were seated in the presence of the Buddha and saw me, did you not rise?”

“Great king, as I was seated in the presence of the Buddha, to have risen on seeing a king of one of his provinces, I should have shown disrespect for the Buddha. Therefore did I not rise.” “Very well, let bygones be bygones. I am told that you are well versed in matters pertaining to the present world and the world to come; that you are versed in the Tipitaka. Recite the Dhamma in our women’s quarters.” “I cannot, your majesty.” “Why not?” “A king’s house is subject to severe censure. Improper and proper alike are grave matters in this case, your majesty.” “Say not so. The other day, when you saw me, you saw fit not to rise. Do not add insult to injury.” “Your majesty, it is a censurable act for householders to go about performing the functions of monks. Send for someone who is a monk and ask him to recite the Dhamma.”

The king dismissed him, saying, “Very well, sir, you may go.” Having so done, he sent a messenger to the Buddha with the following request, “Venerable, my consorts Mallikā and Vāsabhakhattiyā say, ‘We desire to master the Dhamma.’ Therefore come to my house regularly with five hundred monks and preach the Dhamma.” The Buddha sent the following reply, “Great king, it is impossible for me to go regularly to any one place.” In that case, Venerable, send some monk.” The Buddha assigned the duty to the Venerable ânanda. And the Venerable came regularly and recited the Dhamma to those queens. Of the two queens, Mallikā learned thoroughly, rehearsed faithfully, and heeded her teacher’s instruction. But Vāsabhakhattiyā did not learn thoroughly, nor did she rehearse faithfully, nor was she able to master the instruction she received.

One day the Buddha asked the Venerable ânanda, “ânanda, are your female lay disciples mastering the Law?” “Yes, Venerable.” “Which one learns thoroughly?” “Mallikā learns thoroughly, rehearses faithfully, and can understand thoroughly the instruction she receives. But your kinswoman does not learn thoroughly, nor does she rehearse faithfully, nor can she understand thoroughly the instruction she receives.” When the Buddha heard the monk’s reply, he said, “ânanda, as for the Dhamma I have preached, to one who is not faithful in hearing, learning, rehearsing, and preaching it, it is profitless, like a flower that possesses colour but lacks perfume. But to one who is faithful in hearing, learning, rehearsing, and preaching the law, it returns abundant fruit and manifold blessings.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 51)

ruciraṃ vaṇṇavantaṃ sagandhakaṃ pupphaṃ yathā api

evaṃ subhāsitā vācā akubbato saphalā hoti

ruciraṃ [rucira]: attractive, alluring; vaṇṇavantaṃ [vaṇṇavanta]: of brilliant colour; sagandhakaṃ [sagandhaka]: devoid of fragrance; pupphaṃ [puppha]: flower; yathā api evaṃ: and similarly; subhāsitā vācā: the well articulated words; akubbato [akubbata]: of the non-practitioner; aphalā hoti: are of no use

A flower may be quite attractive, alluring. It may possess a brilliant hue. But, if it is devoid of fragrance, and has no scent, it is of no use. So is the well spoken word of him who does not practice it. It turns out to be useless.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 52)

ruciraṃ vaṇṇavantaṃ sagandhakaṃ pupphaṃ yathā api,

evaṃ subhāsitā vācā sakubbato saphalā hoti

ruciraṃ [rucira]: attractive, alluring; vaṇṇavantaṃ [vaṇṇavanta]: of brilliant colour; sagandhakaṃ [sagandhaka]: full of fragrance (sweet-smelling); pupphaṃ [puppha]: flower; yathā api evaṃ: just like that; subhāsitā vācā: well spoken word; sakubbato [sakubbata]: to the practitioner; saphalā hoti: benefit accrues

A flower may be quite attractive, alluring and possessing a brilliant hue. In addition, it may also be full of fragrance. So is the person who is well spoken and practises what he preaches. His words are effective and they are honoured.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 51-52)

agandhakaṃ: lacking in fragrance. The essence of a flower is its sweet-smell. A flower may appeal to the eye. It may be colourful and brilliant. But, if it has no fragrance, it fails as a flower. The analogy here is to the Buddha–words spoken by someone who does not practice it. The word is brilliant, and full of colour. But its sweet-smell comes only when it is practiced.

sagandhakaṃ: sweet smelling. If a flower is colourful, beautiful to look at and has an alluring fragrance, it has fulfilled its duty as a flower. It is the same with the word of the Buddha. It acquires its sweet smell when practiced.

akubbato, sakubbato: these two words stress the true character of Buddhism. The way of the Buddha is not a religion of mere faith. If it were, one has only to depend on external deities or saviours for one’s liberation. But in the instance of the Buddha’s word, the most essential thing is practice. The ‘beauty’ or the ‘sweet-smell’ of the Buddha word comes through practice. If a person merely speaks out the word of the Buddha but does not practice it–if he is an akubbato–he is like a brilliant hued flower lacking fragrance. But, if he is a sakubbato–a person who practises the word of the Buddha–he becomes an ideal flower–beautiful in colour and appearance, and in its sweet-smell.