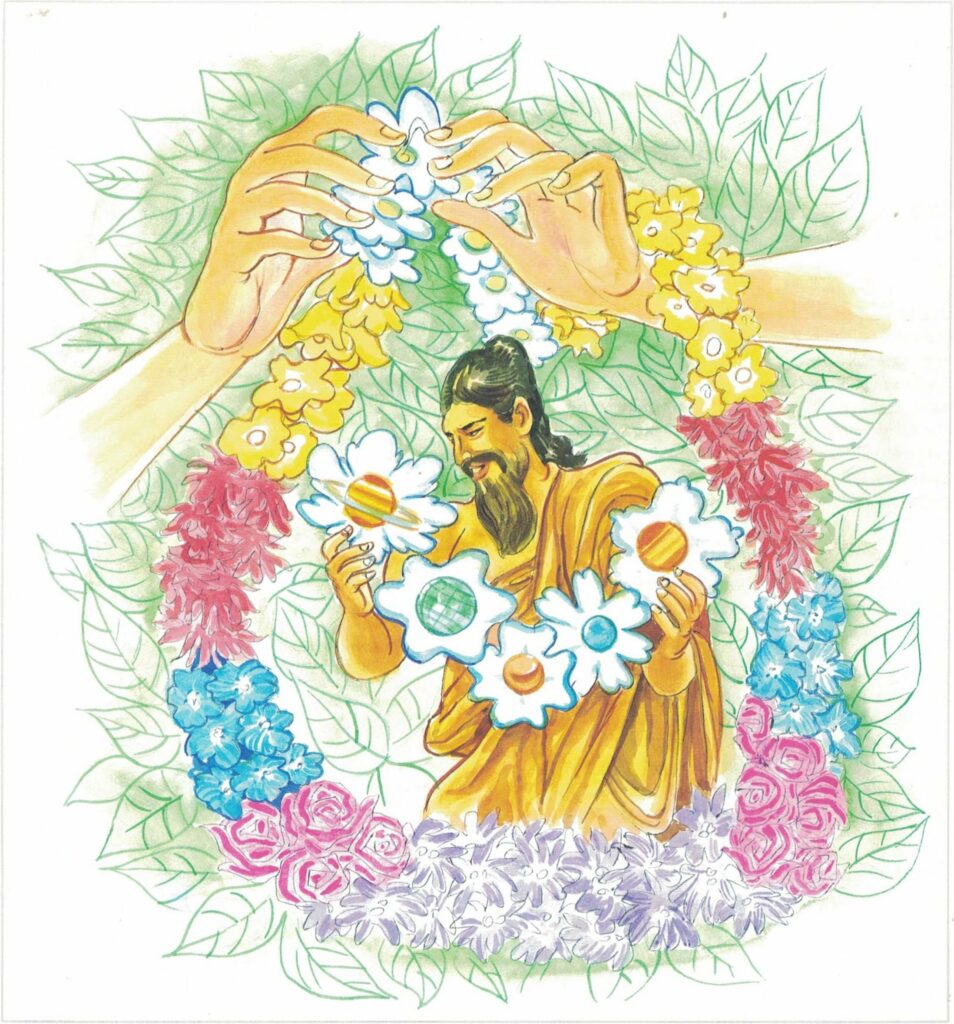

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 44-45:

ko imaṃ paṭhaviṃ vicessati yamalokañca imaṃ sadevakaṃ |

ko dhammapadaṃ sudesitaṃ kusalo pupphamiva pacessati || 44 ||

sekho paṭhaviṃ vicessati yamalokañca imaṃ sadevakaṃ |

sekho dhammapadaṃ sudesitaṃ kusalo pupphamiva pacessati || 45 ||

44. Who will comprehend this earth, the world of Yama, and the gods? Who discerns the well-taught Dhamma as one who’s skilled selects a flower?

45. One Trained will comprehend this earth, the world of Yama, and the gods, One Trained discerns the well-taught Dhamma as one who’s skilled selects a flower.

The Story of Five Hundred Monks

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to five hundred monks.

Five hundred monks, after accompanying the Buddha to a village, returned to the Jetavana Monastery. In the evening, while the monks were talking about the trip, especially the condition of the land, whether it was level or hilly, or whether the ground was of clay or sand, red or black, the Buddha came to them. Knowing the subject of their talk, he said to them, “Monks, the earth you are talking about is external to the body; it is better, indeed, to examine your own body and make preparations for meditation practice.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 44)

ko imaṃ paṭhaviṃ vijessati imaṃ sadevakaṃ yamalokaṃ

ca ko sudesitaṃ dhammapadaṃ kusalo pupphaṃ iva pacessati

ko: who; imaṃ paṭhaviṃ [paṭhavi]: this earth; vijessati: perceives, comprehends; imaṃ Yamalokaṃ ca: and this world of Yama; sadevakaṃ [sadevaka]: along with the heavenly worlds; ko: who; sudesitaṃ [sudesita]: well proclaimed; dhammapadaṃ [dhammapada]: content of the dhamma; kusalo pupphaṃ iva: like a deft garlandmaker the flowers; ko: who; pacessati: gathers, handles

An expert in making garlands will select, pluck and arrange flowers into garlands. In the same way who will examine the nature of life penetratingly? Who will perceive the real nature of life in the world, along with the realms of the underworld and heavenly beings? Who will understand and penetratively perceive the well-articulated doctrine, like an expert maker of garlands, deftly plucking and arranging flowers?

Explanatory Translation (Verse 45)

sekho paṭhaviṃ vijessati imaṃ sadevakaṃ

yamalokaṃ ca sekho sudesitaṃ dhammapadaṃ

kusalo pupphaṃ iva pacessati

sekho [sekha]: the learner; paṭhaviṃ vijessati: perceives the earth; Yamalokaṃ ca: the world of Yama too; sadevakaṃ imaṃ: along with the realm of gods; sekho [sekha]: the learner; sudesitaṃ [sudesita]: the well-articulated; dhammapadaṃ [dhammapada]: areas of the doctrine (understands); kusalo [kusala]: like a deft maker of garlands; pupphaṃ iva: selecting flowers; pacessati: sees

In the previous stanza, the question was raised as to who will penetrate the well-articulated doctrine? The present stanza provides the answer: the student, the learner, the seeker, the apprentice, the person who is being disciplined. He will perceive the doctrine, like the expert garland-maker who recognizes and arranges flowers. It is the learner, the seeker, the student who will perceive the world of Yama, the realm of heavenly beings and existence on earth. He will discard and determine the various areas of the doctrine, like a deft garland-maker who plucks and arranges the flowers into garlands.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 44-45)

sekho: a ‘noble learner’, a disciple in higher training, i.e., one who pursues the three kinds of training, is one of those seven kinds of noble disciples who have reached one of the four supermundane paths or the three lower fruitions, while the one possessed of the fourth fruition, or arahatta-phala, is called ‘one beyond training’. The worldling is called ‘neither a noble learner, nor perfected in learning’.

loka: ‘world’, denotes the three spheres of existence comprising the whole universe, i.e., (i) the sensual world, or the world of the five senses; (ii) the form world, corresponding to the four form absorptions; (iii) the formless world, corresponding to the four formless absorptions. Vijessati = attano ñāṇena vijānissati = who will know by one’s own wisdom? (Commentary).

self: That is, one who will understand oneself as one really is.

sugati: Namely, the human plane and the six celestial planes. These seven are regarded as blissful states.

Devas: literally, sporting or shining ones. They are also a class of beings who enjoy themselves, experiencing the effects of their past good actions. They too are subject to death.

The sensual world comprises the hells, the animal kingdom, the ghost realm, the demon world, the human world and the six lower celestial worlds. In the form world there still exists the faculties of seeing and hearing, which, together with the other sense faculties, are temporarily suspended in the four Absorptions. In the formless world there is no corporeality whatsoever; only four aggregates (khanda) exist there.

Though the term loka is not applied in the Suttas to those three worlds, but only the term bhava, ‘existence’, there is no doubt that the teaching about the three worlds belongs to the earliest, i.e., Sutta-period of the Buddhist scriptures as many relevant passages show.

Yamaloka: the World of Yama. Yama is death–Yama is almost synonymous with Māra.

Māra: the Buddhist ‘Tempter’-figure. He is often called ‘Māra the Evil One’ or Namuci (‘the non-liberator’, the opponent of liberation). He appears in the texts both as a real person (as a deity) and as personification of evil and passions, of the worldly existence and of death.

Later Pāli literature often speaks of a ‘five-fold Māra’:

- Māra as a deity;

- the Māra of defilements;

- the Māra of the Aggregates;

- the Māra of Karma-formations; and

- Māra as Death.

Māra is equated with Death in most instances. ‘Death’, in ordinary usage, means ‘the disappearance of the vital faculty confined to a single life-time, and therewith of the psycho-physical life-process conventionally called ‘Man, Animal, Personality, Ego’ etc. Strictly speaking, however, death is the momentary arising dissolution and vanishing of each physicalmental combination. About this momentary nature of existence, it is said:

In the absolute sense, beings have only a very short moment to live, life lasting as long as a single moment that consciousness lasts. Just as a cart-wheel, whether rolling or whether at a standstill, at all times is only resting on a single point of its periphery: even so the life of a living being lasts only for the duration of a single moment of consciousness. As soon as that moment ceases, the being also ceases. For it is said: ‘The being of the past moment of consciousness has lived, but does not live now, nor will it live in future. The being of the future moment has not yet lived, nor does it live now, but it will live in the future. The being of the present moment has not lived, it does live just now, but it will not live in the future.”

In another sense, the coming to an end of the psycho-physical life process of the Arahat, or perfectly Holy One, at the moment of his passing away, may be called the final and ultimate death, as up to that moment the psycho-physical life-process was still going on.

Death, in the ordinary sense, combined with old age, forms the twelfth link in the formula of Dependent Origination.

Death, according to Buddhism, is the cessation of the psycho-physical life of any individual existence. It is the passing away of vitality, i.e., psychic and physical life, heat and consciousness. Death is not the complete annihilation of a being, for though a particular lifespan ends, the force which hitherto actuated it is not destroyed.

Just as an electric light is the outward visible manifestation of invisible electric energy, so we are the outward manifestations of invisible karmic energy. The bulb may break, and the light may be extinguished, but the current remains and the light may be reproduced in another bulb. In the same way, the karmic force remains undisturbed by the disintegration of the physical body, and the passing away of the present consciousness leads to the arising of a fresh one in another birth. But nothing unchangeable or permanent ‘passes’ from the present to the future.

In the foregoing case, the thought experienced before death being a moral one, the resultant re-birth-consciousness takes as its material an appropriate sperm and ovum cell of human parents. The rebirth-consciousness then lapses into the Bhavaṅga state. The continuity of the flux, at death, is unbroken in point of time, and there is no breach in the stream of consciousness.

sadevakaṃ: the world of the celestial beings. They are referred to as the Radiant Ones. Heavenly Beings, deities; beings who live in happy worlds, and who, as a rule, are invisible to the human eye. They are subject however, just as all human and other beings, to repeated rebirth, old age and death, and thus not freed from the cycle of existence, and not freed from misery. There are many classes of heavenly beings.

kusalo: in this context this expression refers to expertise. But, in Buddhist literature, Kusala is imbued with many significance. Kusala means ‘karmically wholesome’ or ‘profitable’, salutary, and morally good, (skilful). Connotations of the term, according to commentaries are: of good health, blameless, productive of favourable karma-result, skilful. It should be noted that commentary excludes the meaning ‘skilful’, when the term is applied to states of consciousness. In psychological terms: ‘karmically wholesome’ are all those karmical volitions and the consciousness and mental factors associated therewith, which are accompanied by two or three wholesome Roots, i.e., by greedlessness and hatelessness, and in some cases also by non-delusion. Such states of consciousness are regarded as ‘karmically wholesome’ as they are causes of favourable karma results and contain the seeds of a happy destiny or rebirth. From this explanation, two facts should be noted: (i) it is volition that makes a state of consciousness, or an act, ‘good’ or ‘bad’; (ii) the moral criterion in Buddhism is the presence or absence of the three Wholesome or Moral Roots. The above explanations refer to mundane wholesome consciousness. Supermundane wholesome states, i.e., the four Paths of Sanctity, have as results only the corresponding four Fruitions; they do not constitute Karma, nor do they lead to rebirth, and this applies also to the good actions of an Arahat and his meditative states which are all karmically inoperative.

Dhammapada: the commentary states that this term is applied to the thirty-seven Factors of Enlightenment. They are:

(i) the Four Foundations of Mindfulness–namely, 1. contemplation of the body, 2. contemplation of the feelings, 3. contemplation of states of mind, and 4. contemplation of dhammas;

(ii) the Four Supreme Efforts–namely, 1. the effort to prevent evil that has not arisen, 2. the effort to discard evil that has already arisen, 3. the effort to cultivate unarisen good, and 4. the effort to promote good that has already arisen;

iii) the Four Means of Accomplishment–namely, will, energy, thought, and wisdom; (iv) the Five Faculties–namely, confidence, energy, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom;

(v) the Five Forces, having the same names as the Indriyas;

(vi) the Seven Constituents of Enlightenment–namely, mindfulness, investigation of Reality, energy, joy, serenity, concentration, and equanimity;

(vi) Eight-fold Path–namely, right views, right thoughts, right speech, right actions, right livelihood, right endeavour, right mindfulness and right concentration.

yama loka: the realms of Yama. By the realms of Yama are meant the four woeful states–namely, hell, the animal kingdom, the peta realm, and the asura realm. Hell is not permanent according to Buddhism. It is a state of misery as are the other planes where beings suffer for their past evil actions.

vijessati (attano ñāṇena vijānissati): who will know by one’s own wisdom.